Soon I shall be heading to sea on the above Dutch-registered, steel-hulled barque as voyage crew to follow in the footsteps of Ossining’s own Alfred Agate, best known as one of two illustrators for the US Exploring Expedition of 1838 – 1842 (USXX).

Wait, what?

“To sea”?

“Voyage crew”?

“Alfred Agate”??

“US Exploring Expedition of 1838 – 1842”???

Oh yes, I hear all your questions. So consider this the first of several blog posts detailing the life of Alfred Agate, the US XX (aka the Largest All-Sail Exploring Expedition You’ve Never Heard Of), and my 21st century pilgrimage on a tall ship.

Today’s post will focus on Alfred Agate, Ossining artist and International Man of Illustration.

Now, truth to tell, I knew nothing about Alfred or his family until I stumbled into the bottom drawer of a filing cabinet at the Ossining Historical Society and learned about this surprisingly influential family of artists.

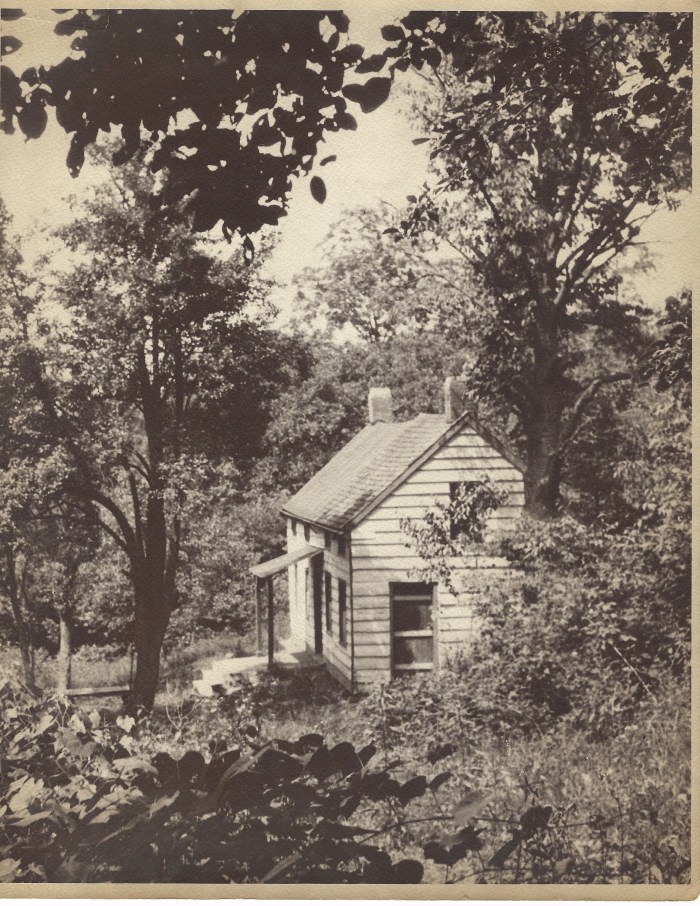

First, perhaps you’re familiar with this house that still stands at the corner of Hudson and Liberty Streets in the Sparta area of Ossining?

c. 2023

Built over 200 years ago by Thomas Agate, it is the grand home of one of the first English settlers in Sparta.

[NOTE: much of the following information comes from a 1968 article written by Ossining historian Greta Cornell, Ancestry.com, and Phillip Field Horne’s A Land of Peace.]

Here’s some background: Alfred’s father, Thomas Agate, was born in Sussex, England c. 1775. He came to Sparta in the 1790s with his siblings John, William, Ann & Mary. In about 1795, the Agates purchased two lots of Sparta land from James Drowley’s estate via a Richard Hillier. They were Baptist/Republicans who didn’t believe in the monarchy, so settling in the recently independent colonies must have been a no-brainer for these motivated Brits.

Thomas seems to have been scrappy and ambitious, and according to Philip Horne, kept a “House of Entertainment” in Sparta until about 1811. (Excellent term, no? Sounds like a strip club to me, although it was likely just a tavern.)

In 1795, he married Hannah Stiles and would continue living and prospering in Sparta. After leaving the “entertainment” business, he would run a store in Sparta, manage the Sparta dock, and buy and sell numerous parcels of land in the neighborhood. When copper was discovered practically right under his house in 1820, Thomas Agate was one of the first to invest in the Westchester Copper Mine Company. Unsurprisingly, nearby Agate Street is named after the family, and the house pictured below was still in the family as late as 1960!

In 1959, home of descendant Melodia Agate Foster Wood

Thomas and Hannah would have at least 4 children:

Edward Priestley Agate:

b. August 29, 1798

m. Mary Williams (7 children “all died young”),

d. November 22, 1872

Frederick Stiles Agate:

b. January 29, 1803

Never married

d. May 1, 1844 (buried in Sparta Cemetery)

Harriet Ann Agate Carmichael

b. March 29, 1817

m. Thomas J. Carmichael c. 1835

d. January 12, 1871 (buried in Sparta Cemetery, though his headstone is currently missing)

Alfred Thomas Agate

b. Feb. 14, 1812

m. Elizabeth Hill Kennedy, 1844

d. Jan. 5, 1845 (buried Mt. Olivet Cemetery, Washington DC)

But Frederick, Harriet and of course Alfred are the ones we are most interested in here.

Older brother Frederick was a precocious and artistic child who, at the age of 15 or so, was sent to study art in New York City with John Rubens Smith. Frederick would then teach his siblings Alfred and Harriet the rudiments of oil painting and find them teachers at the National Academy of Design (which Frederick would help found in 1825 with his bosom friend Thomas Seir Cummings, and painter/telegraph inventor Samuel F.B. Morse.)

At the time, historical and portrait painting was a lucrative career – photographs of course did not yet exist, so painted portraits were the only way to capture a person’s likeness.

Alfred studied with Thomas Seir Cummings at the National Academy of Design (NAD), and by the age of 20 he was exhibiting his paintings at their annual exhibition. By 25, he had his own studio at 25 Walker Street and churned out portraits – both oil paintings as well as miniatures.

Now, during this time, it’s entirely likely (though I have so far found no concrete evidence of it) that Frederick and Alfred met and socialized with Charles Wilkes, the man who would become the leader of the USXX. Wilkes was a Navy man, a talented artist himself, and, most importantly, a skilled navigator, cartographer and surveyor. It does seem that he took some drawing classes at the NAD during the late 1820s/early 1830s.

This connection will become important when the US XX, an expedition that was about a decade in the making, starts to come together in the late 1830s.

In late 1836 our Alfred is offered a position as illustrator for what was then called the “South Seas Surveying and Exploring Expedition.” Here’s his acceptance letter written to Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson:

Courtesy of the National Archives

Now, as promised, I will expound on the development and purpose of said Expedition in a future post. For now, let us concentrate on young Alfred.

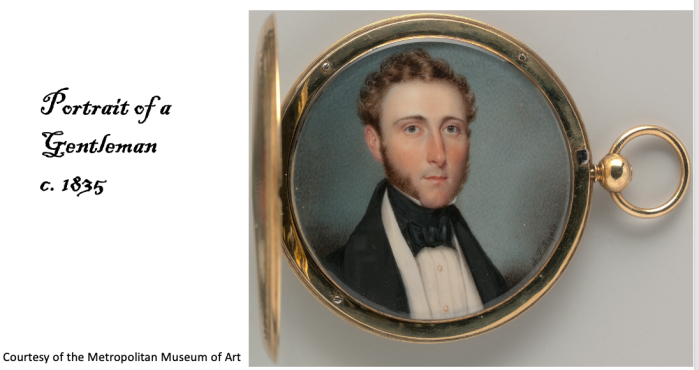

Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society

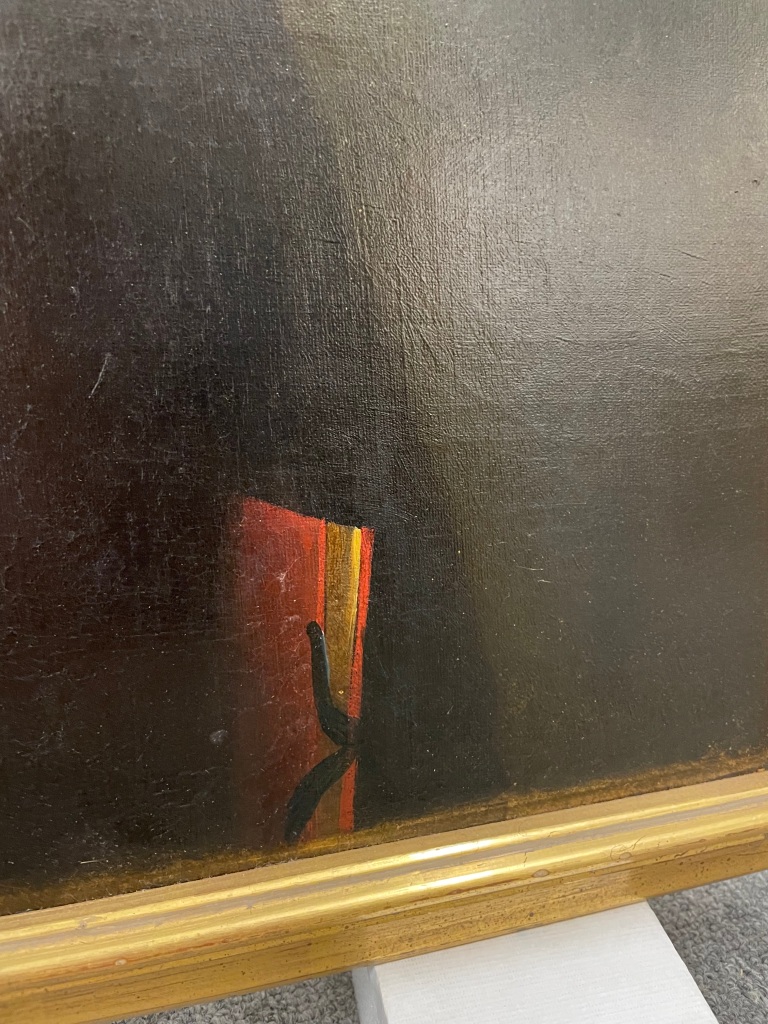

It is believed that brother Frederick painted this portrait just before Alfred left for his voyage to points south. And if you look closely, you can see some subtle iconography in the form of the red sketchbook under Alfred’s left arm and the boat anchors on his fetching gold buttons. Here they are in close up for your amusement:

On August 18, 1838 six ships set off from Norfolk, Virginia on what is often described as the world’s last all-sail exploration expedition:

Approximately 440 men served – 82 officers, 345 sailors, 7 naturalists/scientists and 2 illustrators.

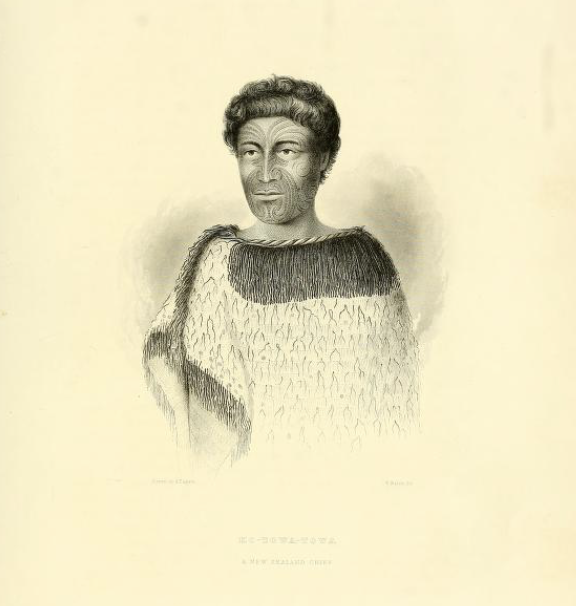

Alfred shared the load with fellow illustrator Joseph Drayton and their importance to the expedition cannot be underestimated. With no ability to photograph anything, it was up to these two artists to document as many plants, animals, landscapes, and people as possible. (Knowing that the US XX sent back about 40 TONS of artifacts, it would have been an Herculean task to document it all.) To that end, to save time, the illustrators often used the Camera Lucida, an optical projection device that some say was developed in the 1600s, though it wasn’t patented until the early 1800s.

Alfred tended to do landscapes and portraits, while Drayton focused on botanical and animal illustrations

Sometimes they worked from sketches of others – many of the officers were passable artists themselves and would give sketches to the illustrators to work from.

During the course of the expedition, hundreds of sketches, watercolors, oils, and later, engravings were made. Just a small number of these were published in the multi-volumed post-expedition Narrative of the USXX.

Sadly, some of Agate’s work was lost in the wreck of the Peacock in 1841, and in a later fire at the Philadelphia publisher’s plant, but there still are a large number extant.

Today, the Naval History and Heritage Command website has digitized and interpreted its significant collection of Alfred’s USXX illustrations. Check it out here.

The route of the USXX is mind-boggling:

And our Alfred sketched wonderful portraits throughout — here are just two of many:

Alfred returned to New York on June 10, 1842, landing at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. After spending a week in quarantine, he likely came back to Ossining to recuperate at his parents’ home on Liberty Street. He was apparently unusually sickly on the expedition (at least, according to Charles Wilkes’ memorial to him). He regained enough strength to relocate to Washington, DC to finalize illustrations for the first volume or two of the Narrative of the US Exploring Expedition written by Charles Wilkes. He also married Elizabeth Hill Kennedy in October 1844. But, tragically, his life was cut short by tuberculosis, that scourge of the 19th century, and he died just a few months after his wedding.

He was fondly remembered by all who knew him, and Senator James A. Pearce of Maryland would honor him with the following words:

The delicacy and sensibility of the man seemed to characterize the productions of his pencil. His drawings, which have been published, and those which remain to be published, show a truthfulness and harmony which stamp him as an artist of the highest order of talent.

RIP Alfred Agate.

Type your email address below to subscribe and make sure you don’t miss the next exciting posts about the USXX and the upcoming voyage I’ll be taking to Tahiti, Tonga & Fiji in July/August 2024 to see the actual sights our Alfred memorialized!

Or click here for the next post in the series on the Bark Europa.