I am back in the 21st century, with access to speedy internet! So, in the next few weeks I will be playing catch up and posting about Tahiti, Tonga and Fiji – all sites our Sparta artist Alfred Agate visited and memorialized on the US Exploring Expedition of 1838 – 1842, and all places that I too visited this July/August of 2024.

*********************************************************************************************************

Sign up here if you’re interested in staying in the know:

*********************************************************************************************************

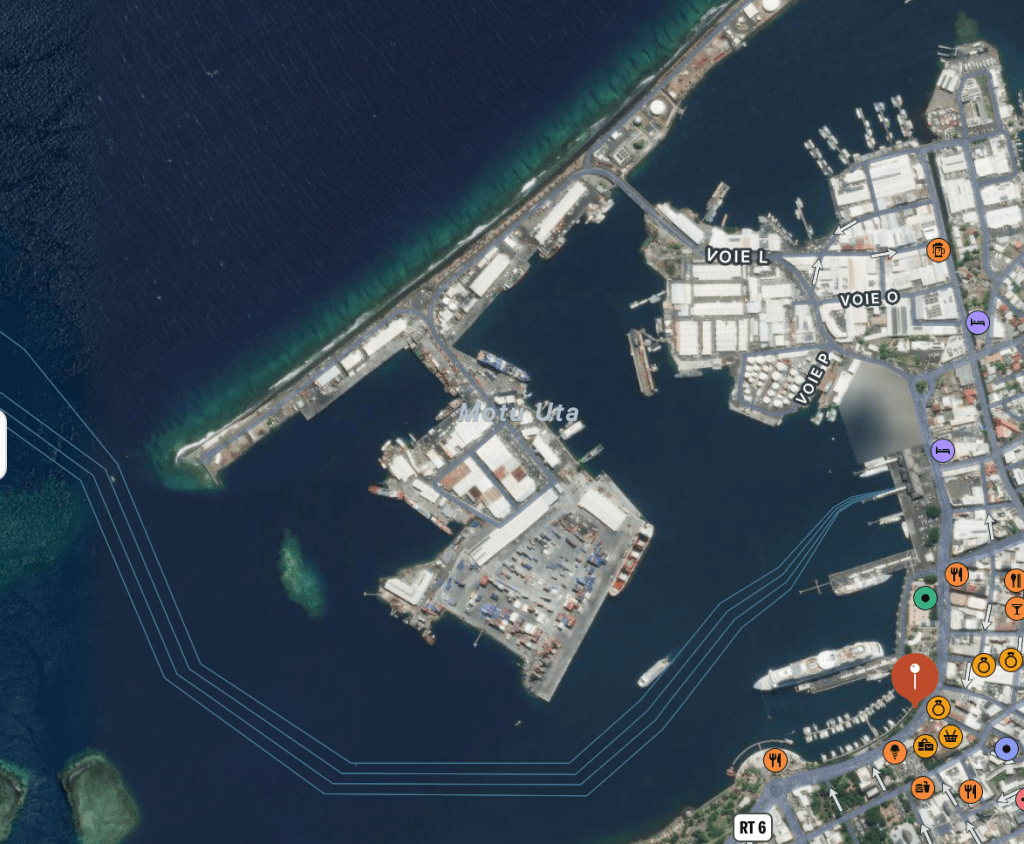

Tahiti!! I joined my ship, the Bark Europa, on July 3, 2024. We were moored in the harbor of Papeete next to a small cruise ship and a couple of giant yachts.

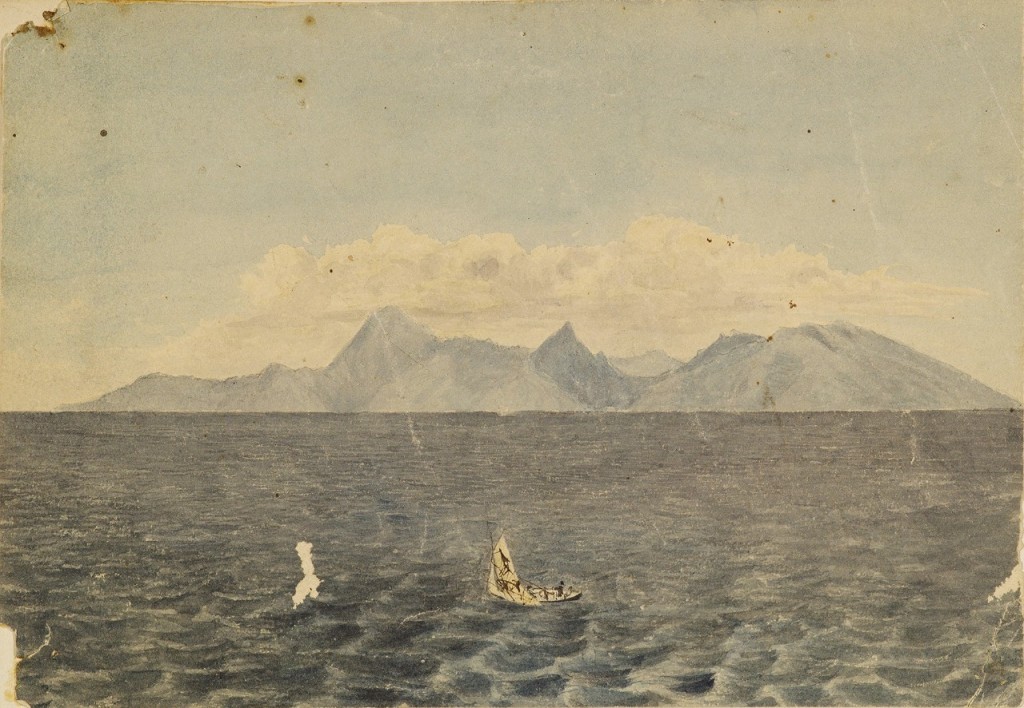

Now, I know I posted these pictures of Eimeo/Moorea before (taken from Papeete), but I continue to be thrilled by this first view that I shared with Alfred Agate, over a 185 years apart:

Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

Photo by John Curvan

In this post I’m going to give a brief history of Tahiti and include more images from Alfred Agate.

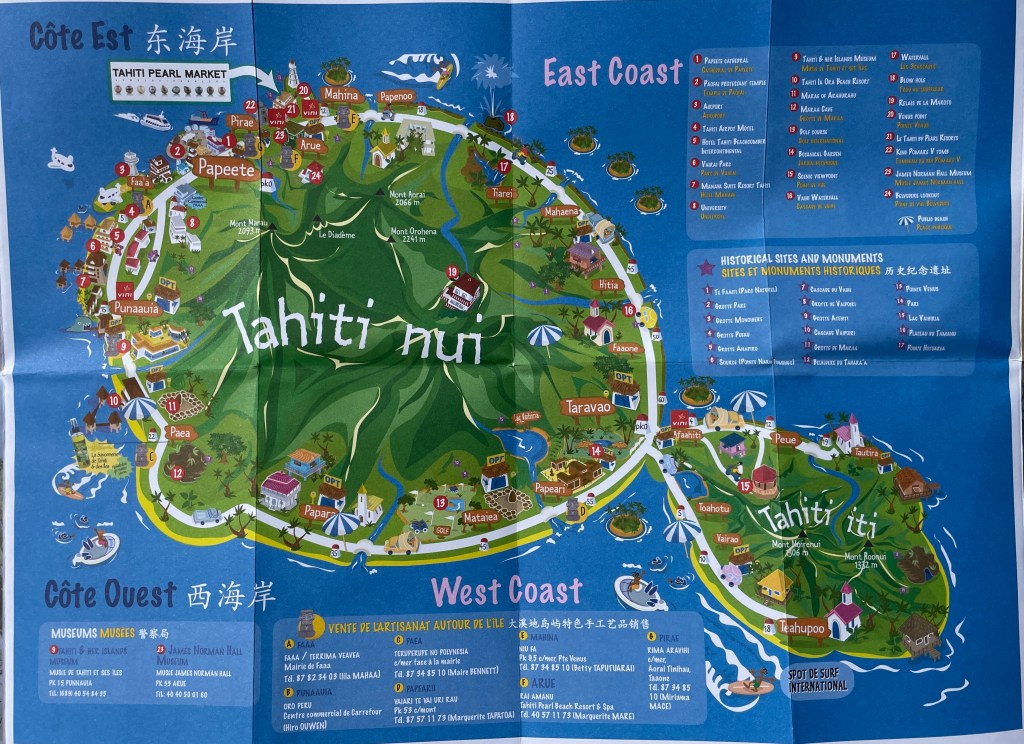

Volcanically formed about a million years ago (don’t you love stories that go back before humans arrived on the scene?) Tahiti actually consists of two major land masses – Tahiti Nui, where Papeete is located, and Tahiti Iti, a smaller but attached land mass to the south. [Fun fact: The surfing competition of the 2024 Olympics took place off Teahupo’o, a beach located on Tahiti Iti.]

But Tahiti is just one of many islands that comprise the Society Islands (Mo’orea, Raiatea, Bora Bora, Taha’a and Huahine are some of the next biggest.) This island group was named by Captain James Cook, supposedly to honor the Royal Society who bankrolled his 1769 voyage of exploration. Today, along with the Tuamotus, Marquesas, Gambier and Austral island groups, these archipelagos comprise what is today known as French Polynesia, one of the remaining overseas colonies of France.

Current thinking is that Tahiti was first settled around 500 BCE. Originating in what is today considered Southeast Asia (think Taiwan, Indonesia, Singapore) these proto-Polynesians were skilled sailors and navigators who island-hopped to Fiji, Samoa and Tonga in outrigger canoes that were up to 90 feet long and could transport people, animals and supplies.

Theirs was a complex society, a clan-based system with a hierarchy of chiefs and nobles and religious leaders. Their culture, language, art, ritual, dance and music would be disseminated throughout what is today considered Polynesia.

This image represents the Polynesian method of navigational wayfinding. The octopus’ head, “Havai’i”, is centered on the island of Raiatea in what is today’s French Polynesia. (Tahiti is just to the east, near Tuamotu.)

It’s not clear exactly when Tahiti was first visited by Europeans or by whom – Spanish explorer Juan Fernandez might have been the first to land in the 1570s, but then some think it was a Portuguese explorer Pedro Fernandes de Queiros in 1606. The historical record is also unclear about what happened next, until 1767 when British Captain Samuel Wallis in the HMS Dolphin, definitively landed in Matavai Bay in Tahiti and, using his guns, steel (and probably a few germs) forced the local Chief, Oberea, to, uh, cooperate with the British.

Ahem.

The next year, the French explorer Louis de Bougainville anchored his ships La Bordeuse and Etoile off Tahiti for about 10 days and was apparently favorably impressed with the welcome he received from the Tahitians. (Paul Theroux, in his curmudgeonly book These Happy Isles of Oceania, tells a likely apocryphal story about this visit, when a “barebreasted Tahitian girl climbed from her canoe to a French ship under the hot-eyed gaze of 400 French sailors who had not seen any woman at all for over six months. She stepped on the quarterdeck where she slipped the flimsy cloth pareu from her hips and stood utterly naked and smiling at the men.” And thus the Edenic myth of Tahiti began. Sigh.)

1769 was Captain James Cook’s first visit, in the HMS Endeavour, to observe the transit of Venus. (He would return twice more in the 1770s.)

1787 is of course the year the infamous Captain William Bligh would dock his HMS Bounty at Point Venus and spend five months collecting breadfruit plants in an unsuccessful attempt to find cheap food with which to feed enslaved Caribbean sugarcane workers. And yes, Mutiny on the Bounty was a real thing (though there are those who take great exception with this enduring portrayal of Bligh. A gifted navigator, there was more to him than just all the floggings he ordered . . .)

By the end of the 18th century, whalers had expanded their hunts into the Southern Ocean and Tahiti was a popular stop for resupplying their ships. The Tahitian people quickly learned how to trade with the Europeans, and a flourishing economy of weapons, iron, alcohol and prostitution was established.

In 1797, the first missionaries landed to convert the “heathens.” Today, most Tahitians identify as Christians.

When the US Exploring Expedition arrived in September 1839, Tahitian culture had been irrevocably changed. For starters, the population is thought to have plummeted from an estimated 180,000 to about 8,000. And by the time the USXX showed up, Christian missionaries had made their mark — nudity was banned, as were tattoos, dances and other rituals.

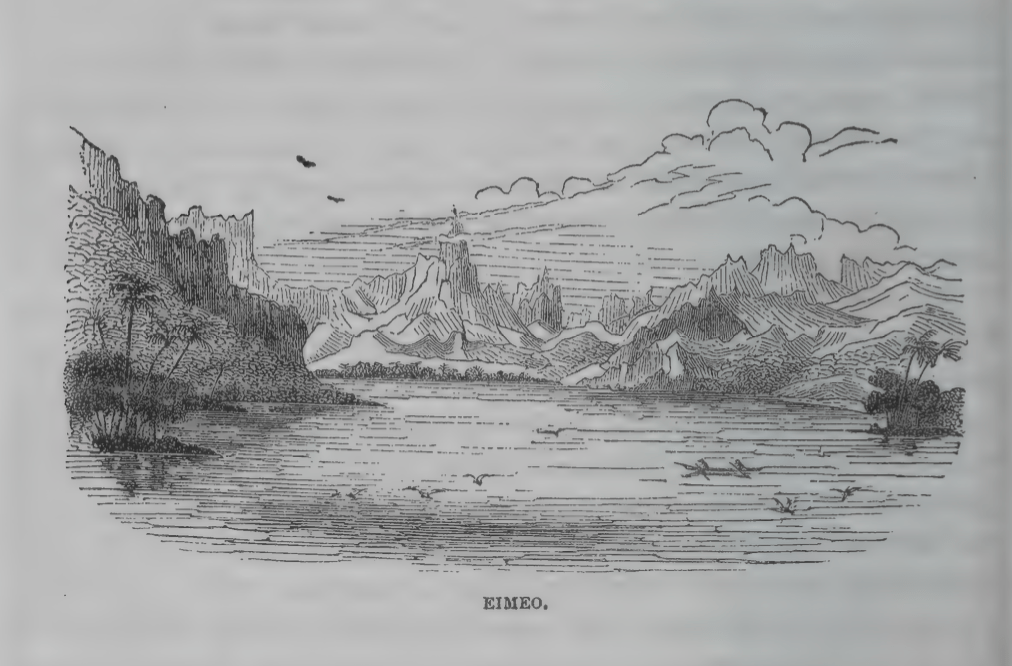

Still, our Alfred Agate was able to create numerous images of Tahitians going about their daily lives. And I was able to see another site from aboard ship that Alfred Agate had also seen and drawn from almost the same vantage point:

(formerly Taloo Bay, Eimeo)

Photo taken by James Walters

Tahitian girl with the hau, sketch by Alfred Agate, September 1839

From The Narrative of the US Exploring Expedition, volume 2

Today, you won’t see anyone wearing the hau, but you will find numerous crafts made with pandanus leaves in the same braided fashion:

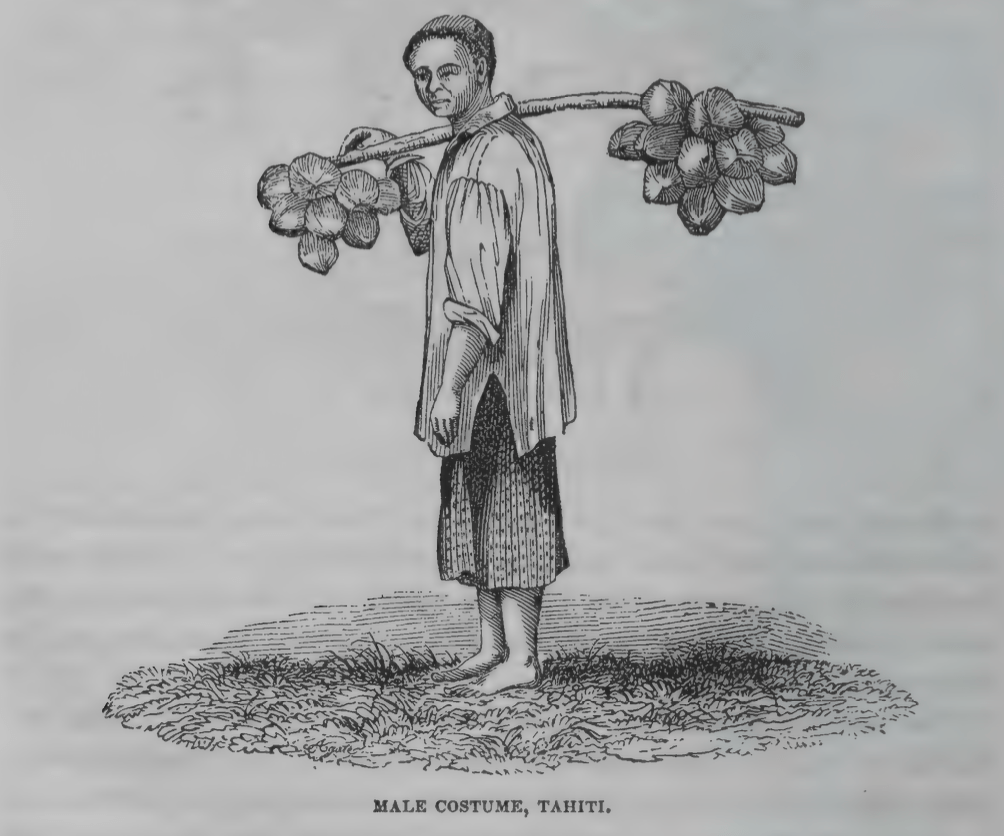

The hat on the man below was likely woven from pandanus:

From The Narrative of the US Exploring Expedition, volume 2

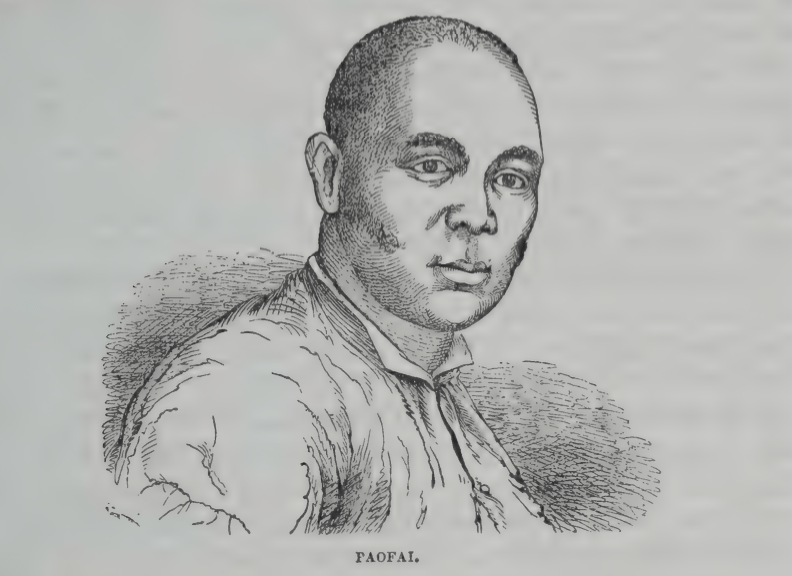

Now, below is an example of Alfred Agate’s artistry being deployed as a form of diplomacy. This is a portrait of Paofai, a chief and an advisor to Queen Pomare IV. Expedition leader Lt. Charles Wilkes wanted a meeting with Queen Pomare to present grievances from US sailing crews regarding their treatment in Tahiti. The Queen was due to give birth so was unable to meet, but sent Paofai as her emissary. Having Agate sketch a portrait of local leaders was a tactic Wilkes would employ on numerous occasions to encourage good feelings and cooperation:

From The Narrative of the US Exploring Expedition, volume 2

And if you slog through volume 2 of Charles Wilkes’ Narrative of the US Exploring Expedition, you’ll read the following description of Paofai, which exemplifies Wilkes’ confusing interpretations and style of writing: “Paofai, a chief who holds the office of chief judge, and who is generally considered as the ablest and most clear-headed man in the nation, is accused of covetousness, and a propensity to intrigue.”

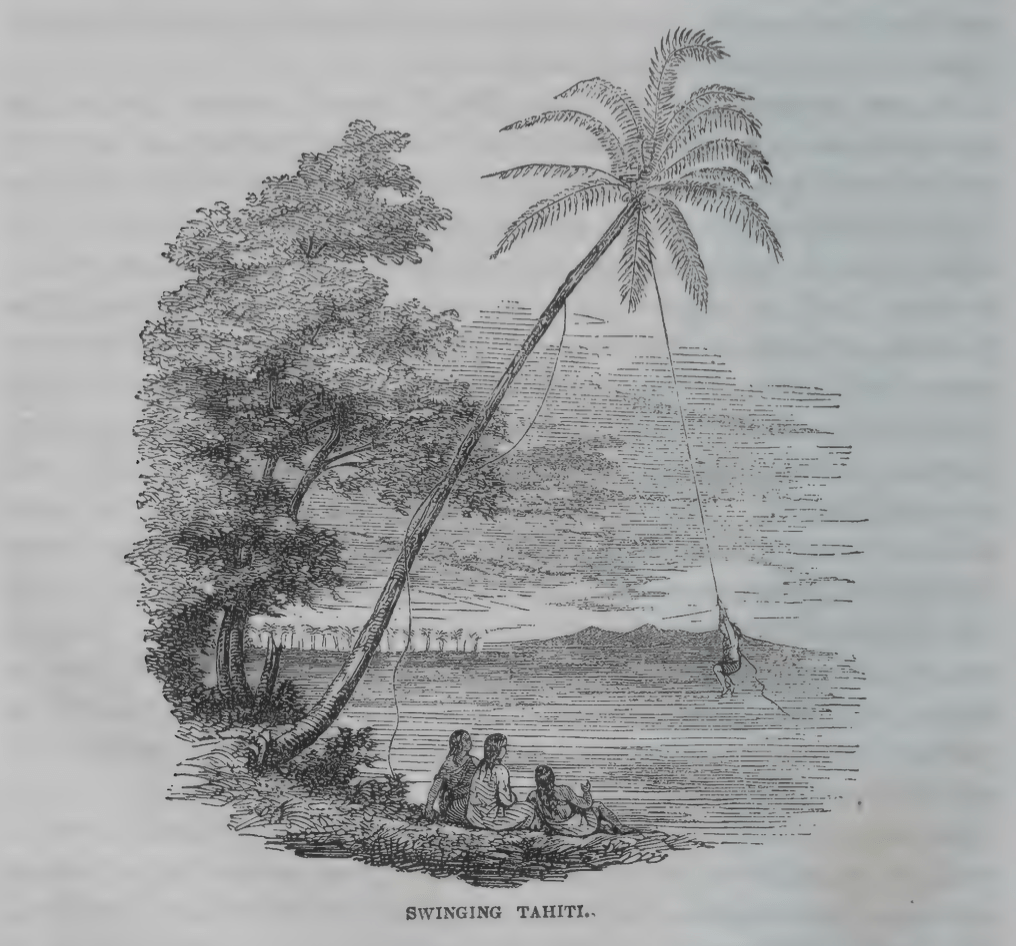

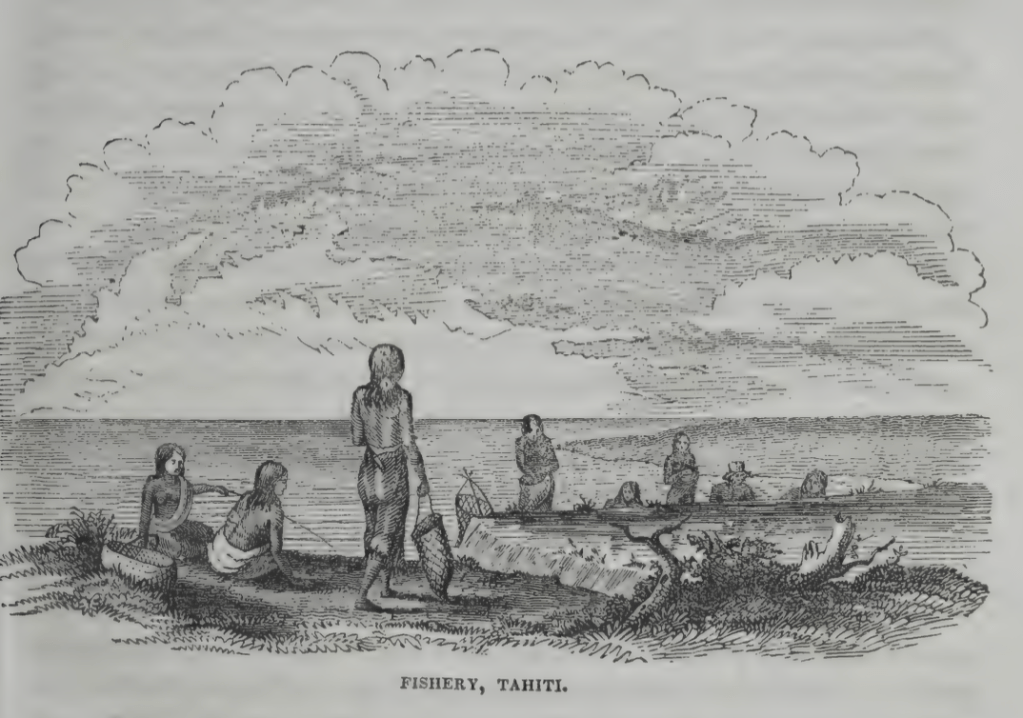

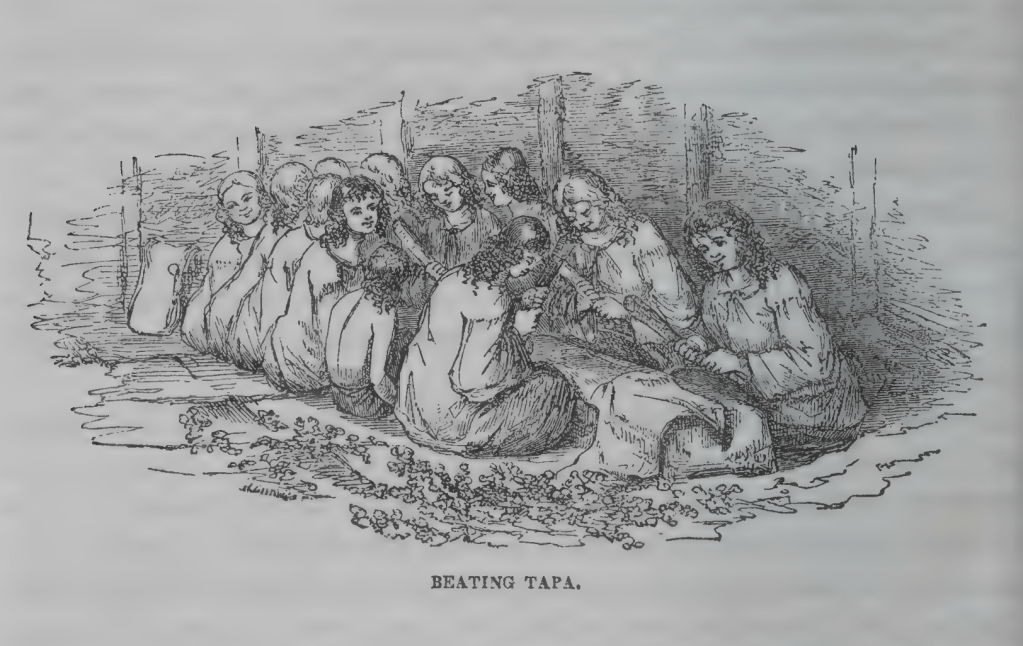

Finally, here are some more Agate images of daily Tahitian life from the Narrative . As you can see, for the most part the people are dressed in demure, European-style clothes.

Check back soon for Posts #8 and 9 and learn all about the realities of tall ship sailing, kava (a traditional intoxicant) and a Tongan umu (feast).