Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Carrie Chapman Catt

1859 – 1947

Suffragist Leader

President, National American Women’s Suffrage Association

President, International Women’s Suffrage Association

Founder, National League of Women Voters

Founder, National Committee on the Cause and Cure of War

****Local Connection: Juniper Ledge, North State Road****

Carrie Chapman Catt (née Lane) was born in Ripon, Wisconsin in 1859. Unusually for that time and place, she went to college (Iowa State Agricultural College) and earned her Bachelor of Science degree in 1880. She became a teacher, a principal, then Superintendent of her Iowa school district.

Courtesy Digital Collection, Iowa State University Park Library

In 1880, she married husband #1, Leo Chapman, editor of the Mason City Republican, who held extremely progressive ideas for the time, but died of typhoid fever within a couple of years. In 1885, she married husband #2, George Catt, a wealthy engineer and fellow Iowa State alum. He apparently was quite supportive of her involvement in the fight for women’s rights.

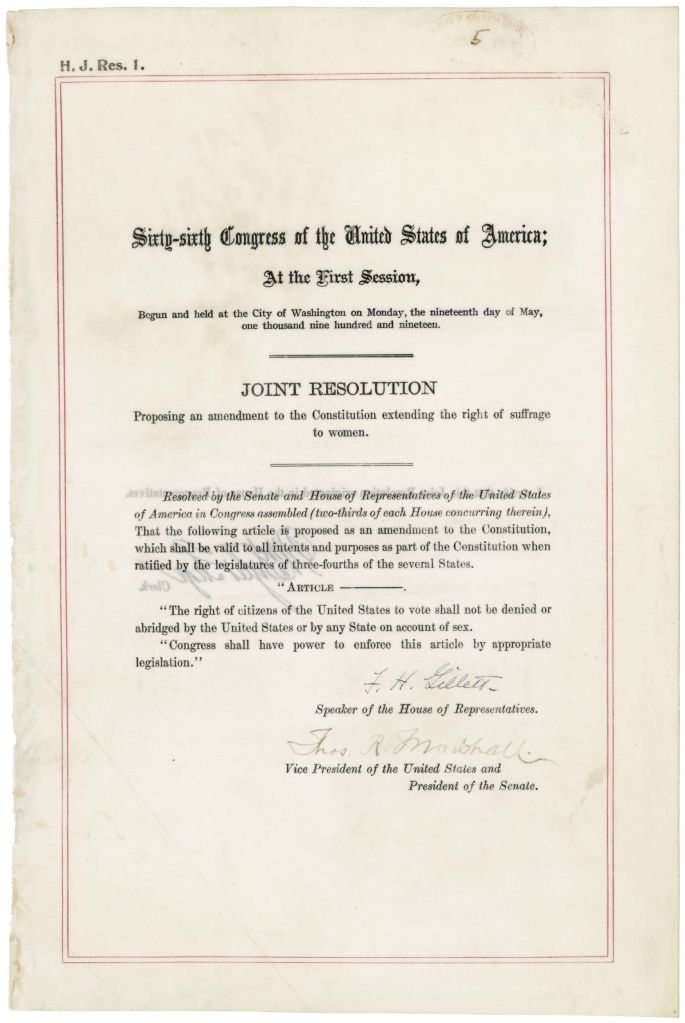

The Constitutional Amendment to give women the right to vote was first proposed in 1878. Catt became involved with the fight soon after. By 1890, she was president of the Iowa Women’s Suffrage Association, running it with great skill. From there, Catt came to the attention of Susan B. Anthony, the Grande Dame of suffragists, who, in 1900, anointed Catt as her successor as President of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Catt was its President when the Nineteenth Amendment was passed in 1920, recognizing women’s right to vote.

3/4ths of the States needed to vote to ratify this amendment and they did, allowing this to become the law of the land on August 26, 1920

Courtesy National Archives

Arguably, it was Catt’s stewardship and steady hand that helped unite all the different factions and finally win the vote for women.

Catt would purchase Juniper Ledge, her home in Ossining, in 1919 and live there until 1928 with her companion Mary Garrett Hay:

She and Carrie Chapman Catt lived together from c. 1900 under Hay’s death

Courtesy of the University of Rochester

The story goes that the estate was called Juniper Ledge because of its abundance of juniper trees.

Today this structure is on the US National Register of Historic Places

Image originally published in Queer Places: Retracing the Steps of LGBTQ People Around the World by Elisa Rolle

In a 1921 New York Times article detailing a picnic she hosted for 100 members of the League of Women voters, Catt is quoted as saying “I know that the juniper is useful in making liquor, and that is why I bought the place – so no one would have opportunity to use the trees for that purpose.” She served her guests coffee and orangeade.

According to another New York Times article, this one from 1927, Juniper Ledge was quite impressive: “The estate is one of the show places of Northern Westchester, and includes sixteen acres of extensively developed land fronting on two roads. The residence, on a knoll overlooking the countryside, is a modern house of English architecture containing fourteen rooms and three baths. A gardener’s cottage, stables, a garage and a greenhouse are also on the property.” Catt affixed brass plaques with the names of famous suffragettes to fourteen trees – and some of those plaques are reportedly in the archives at Harvard University.

From her Juniper Ledge home, she started the League of Women Voters in order to give women information to help them make informed voting decisions. She also was a big supporter of Prohibition, the League of Nations and its successor the United Nations, spending much of her time on crusades for world peace and international disarmament.

Catt sold Juniper Ledge in 1927 and purchased a home at 120 Paine Avenue in New Rochelle. Sadly, her companion Mary Garrett Hay died shortly after they moved.

Catt lived on, staying active right up until her death in 1947. She and Hay are buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. The inscription on their joint tombstone reads, “Here lie two, united in friendship for thirty-eight years through constant service to a great cause.” (Here’s Catt’s obituary if you want to learn more about her life. It makes me tired just to read about all the things she accomplished.)

So, the next time you drive on North State Road, keep an eye out for this old driveway pillar and know that a very influential and historically important woman lived just up the hill.

CONTROVERSY

We would be remiss if we didn’t address the controversy that has swirled around the US women’s suffrage movement almost since its inception.

Some have perceived that it was a racist one, with white women keeping Black women on the fringes of the movement ostensibly to avoid antagonizing the Southern vote.

Carrie Chapman Catt would address these concerns in a speech she delivered in 1893: “If any say we would put down one class to rise ourselves, they do not know us. The woman suffrage movement is not one for woman alone. It is for equality of rights and privileges, and it knows no difference between black and white.”

However, by 1903, Catt and many of her colleagues would state that the national women’s suffrage movement was solely concentrating on removing the “sex restriction” for voting. They seemed perfectly content to let the individual States to determine what, if any, qualifications were deemed necessary to allow women to vote.

And in 1919, Catt would continue to respond to such concerns, such as those from the NAACP who feared that Black women would not be allowed to vote in southern states if the proposed suffrage amendment did not include specific language to include all races, by repeating “We stand for the removal of the sex restriction, nothing more, nothing less.”[1]

This controversy re-emerged forcefully in 1995, right before Iowa State University (formerly Iowa State Agricultural College) was set to name a campus building in Catt’s honor.

In an article, published in the Uhuru! newsletter of the ISU Black Student Alliance entitled “The Catt’s Out of the Bag: Was She Racist?” sophomore Meron Wondwosen argued that Catt and other white suffragists employed racist strategies to gain Southern support for the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Wondwosen referenced examples of Catt giving lectures in Southern states and stressing that women’s suffrage would reinforce white supremacy, discouraging Black suffragists from participating in marches and rallies, and belittling immigrants and Black people.

After several years of research, reflection and discussion, Iowa State decided not to take her name off the building, saying:

“The crux of the matter is that while Catt made statements that are likely to be considered racist, there is also an abundance of declarations upholding and even defending other races. This duality and implicit contradiction is what makes the work of this committee very difficult—and it is what makes Catt such an ambiguous figure when it comes to questions of racism. It adds layers to Catt, her work, how she viewed the world, and how the world viewed her. These may begin to shed light on how compromises were made to achieve an ultimate goal.[2]

Several of the arguments for removing Catt’s name from Catt Hall were based on Barbara Andolsen’s 1985 book Daughters of Jefferson, Daughters of Bootblacks. Andolsen, a feminist theologian, documented some of the frankly bigoted tactics white suffragists used to win passage of the 19th Amendment. Despite this, however, Andolsen believed most suffragist leaders were “women of integrity” committed to gaining the vote for all women. She argued that these leaders didn’t condone segregation or manipulate racist ideologies out of bad intentions, but out of political necessity in a racist society.

In the 2020 PBS program Carrie Chapman Catt, Warrior for Women, historian Beth Behn explored why Catt, generally a progressive thinker and leader, used racism in the suffrage movement. Behn suggested that Catt felt a sense of urgency, fearing that the opportunity to secure a Federal amendment could close. Behn noted that other developed countries, like Great Britain and France, didn’t grant women suffrage until years later, reinforcing the suffragists’ urgency.

A life-long pacifist, Catt endorsed America’s entry into World War I in 1917 in order to gain President Woodrow Wilson’s support for women’s suffrage. She would spend the rest of her life working for peace and disarmament.

Food for thought . . .

[1] Carrie Chapman Catt, letter to John Shillady, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, May 6, 1919.

[2] 2023 Catt Hall Review Final Report 2023, p. 27; https://iastate.app.box.com/s/rw7igjtl5iet6vb6s3xdu3yfkhqin9ck