This is the third of the series documenting my Summer 2024 voyage to the South Pacific. See here for my previous post.

Today’s post will give a blog-length history of the US Exploring Expedition of 1838 – 1842 (aka the US XX). However, if you really want an excellent, in-depth study, I highly recommend reading Nathaniel Philbrick’s Sea of Glory. He does a magnificent job of synthesizing previous histories and making a corking good story of it all:

Known by numerous names – South Seas Surveying and Exploring Expedition, the US South Seas Exploring Expedition, the Charles Wilkes Expedition, it took over 10 years for this expedition to come to fruition.

Its inspiration is often laid at the feet of Captain John Cleves Symmes, Jr, a curious veteran of the War of 1812 (and nephew of a Revolutionary War Colonel of the same name). Somehow, Symmes came to believe that the world was hollow and that the entrance to this undiscovered realm could be accessed through the South Pole.

In 1818, Symmes boldly mailed out 500 copies of his “Circular No. 1” in which he stated:

“I declare the earth is hollow, and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentrick spheres, one within the other, and that it is open at the poles 12 or 16 degrees; I pledge my life in support of this truth, and am ready to explore the hollow, if the world will support and aid me in the undertaking.”

This “Holes in the Poles” theory was not met with great enthusiasm, but it did attract some attention, perhaps most importantly that of New England merchants and whalers. They loved the idea of an expedition that would explore the South Seas, possibly find them undiscovered whaling and sealing grounds, create accurate charts and maps of the area, and maybe even enter into treaties with the islanders. Thanks to President John Quincy Adams, who believed that “The object of government is the improvement of the condition of those who are parties to the social compact,” Congress passed a resolution in 1828 to send a ship to the Southern Ocean. Congress did not, however, appropriate any funds for it.

[Sidebar on President J. Q. Adams, a president that I only know as a whiny politician from the musical “Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson.” He had remarkably big ideas and believed that America would be doomed to “perpetual inferiority” if she did not step up and contribute to the world of discovery and knowledge. To that end, he tried to establish universities, museums and observatories. An exploration of this magnitude fit in nicely with his worldview.]

Now, no doubt Adams’ desire to sponsor an expedition to the South Seas was also influenced by the fact that many of his Massachusetts friends included the aforementioned whalers and merchants.

But there was still such distrust in leaders and government left over from America’s colonial experiences that it was hard to get Congress to act on anything “frivolous” like science or exploration. Adams was a one-term President and couldn’t get the US XX together before President Andrew Jackson took over. And as we all know, Andrew Jackson was not at all interested in exploration (unless it was in the US and involved massacring indigenous people,) nor was he interested in education or broadening world knowledge. However, by the end of his second term, Jackson started to think that such an ocean expedition seemed very cool and so got the US Navy involved and encouraged Congress to make it happen.

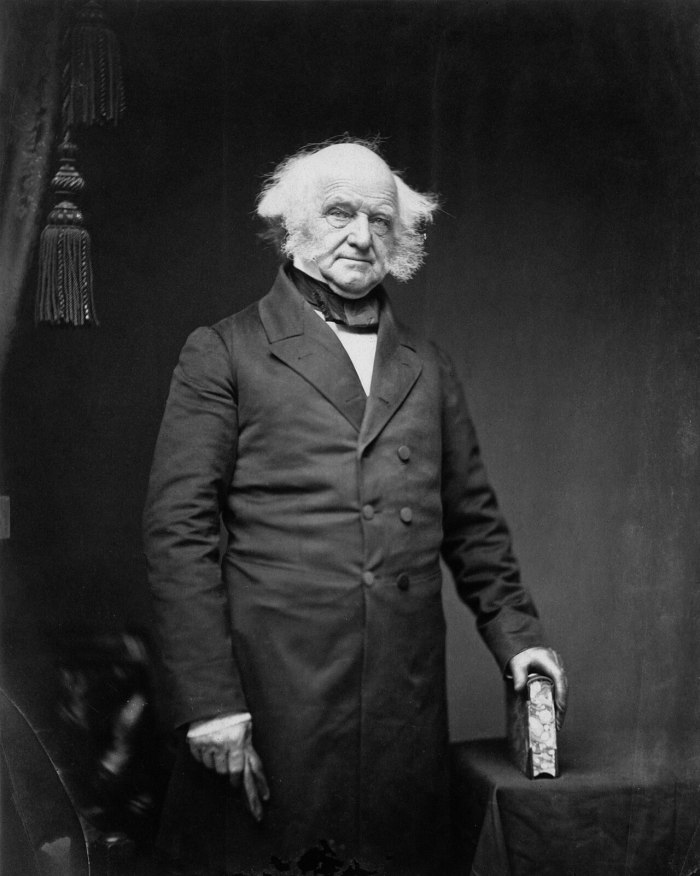

However, it took New Yorker President Martin Van Buren to push it across the start. But by the time things were falling in place for the USXX in the mid-1830s, there had been so much chaos surrounding the expedition, and so many commanders had come and gone, that no Navy man worth his grog wanted command of what began to be called the “Deplorable Expedition.”

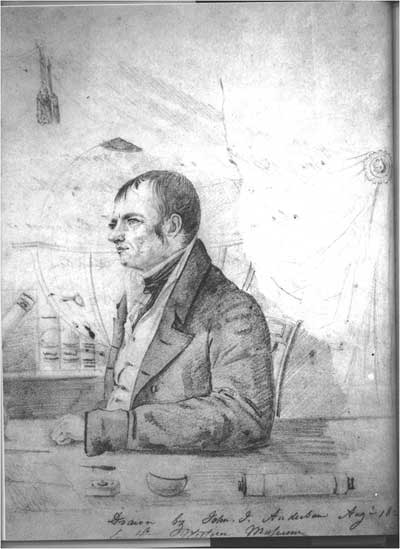

Enter Jr. Lt. Charles Wilkes to organize and command the expedition. (Note that Wilkes was a mere Lieutenant though in command of an expedition with six ships. Pretty unheard of in the world of the US Navy, but there was no one else willing to take on this command. His lowly rank would become a great bone of contention for him, since most of the captains of his expedition’s six ships outranked him. This, combined with his inflexible personality and inexperience as a leader would create numerous problems going forward. But more on this in another post.)

By the time the Expedition shoved off from Hampton Roads, VA on August 18, 1838 its price tag had swelled to over $300,000 (around $10 million in today’s dollars), an astonishing amount for the nation at the time.

In a celebratory speech at the Expedition’s departure, Secretary of the Navy James Paulding would proclaim that the Expedition’s goal was “Not for conquest but for discovery.”

As a reminder, here’s a map of where the Expedition went:

The accomplishments of the Expedition are quite impressive:

- Over 280 islands were surveyed

- Over 180 charts created (some were still being used during WWII!)

- Some 800 miles of Oregon coast and its interior were explored and mapped

- Around 1500 miles of Antarctic coast were charted, and the USXX was the likely the first to discover that Antarctica was a separate land mass (there’s still some question on this point) but Charles Wilkes had this factoid chiseled onto his tombstone.

- Contributed to the rise of science in America, the evolution of navigation, and the development of the fields of botany and anthropology

- The 40-tons worth of plants, animals and artifacts collected becomes the core of the Smithsonian Museum. See more on that here.

Just as a reminder of how large this expedition was, here are the details of six ships that originally comprised it:

Now, for an expedition whose purported purpose was “To extend the bounds of science and promote knowledge,” out of the 400-plus crew, only nine were considered “scientifics.” And our Alfred was considered one of this nine.

These gentlemen were:

James Dwight Dana Minerologist/geologist/Volcanologist/zoologist

Horatio Hale Philologist(precursor to Anthropologist)/linguist

Titian R. Peale Naturalist

Charles Pickering Naturalist/Doctor

William D. Brackenridge Botanist/Horticulturalist

William Rich Botanist

Joseph Couthouy Conchologist (Study of molluscs)/linguist/paleontologist

Alfred T. Agate Artist

Joseph Drayton Artist

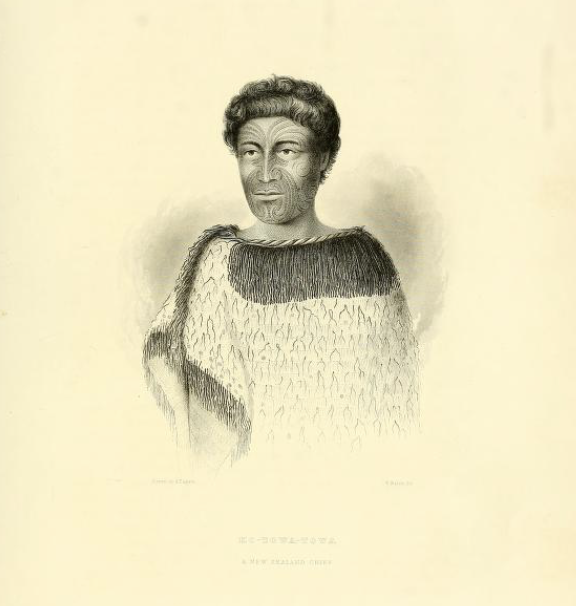

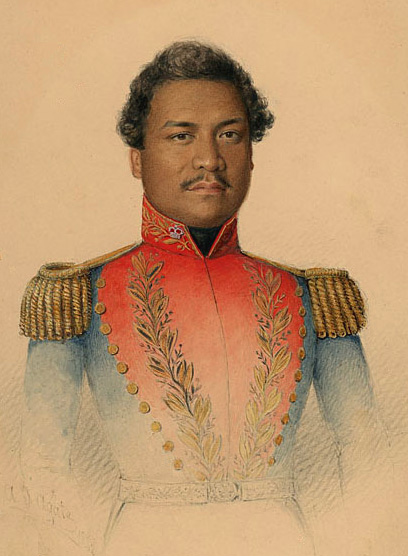

Many of them went on to important careers in their chosen fields, adding greatly to the store of knowledge on the natural world. And, thanks to their US XX work, many new species of birds, plants and animals were discovered, collected and studied. Further, thanks to Alfred Agate, records of the unique cultural patterns of dress, tattoos and rituals of the different South Pacific Island nations was documented.

The perils facing the Expedition were great: there were few accurate charts or maps to navigate through the shoals and coral reefs of the islands. The indigenous people were, for the most part, often and understandably hostile towards Europeans coming to their islands and demanding food, water and other supplies. There was no way to communicate between ships except by cannon, lights and flags, meaning that sometimes days or even weeks would go by before they resumed contact. One ship, the Sea Gull, was lost at sea somewhere between Tierra Del Fuego and Valparaiso, Chile during the first year, never to be heard of again. Another ship was wrecked and lost at the mouth of the Columbia River. About 20 of the crew died during the four-year voyage from disease, injury or attacks.

But the Expedition accomplished its mission and put America on the world stage, though perhaps not as spectacularly as President Adams had hoped.

Stay tuned for more about Lt. Charles Wilkes, and stories about the Expedition’s encounters on Tahiti, Tonga and Fiji.

If you haven’t already subscribed and are interested in following this journey, you can do so here:

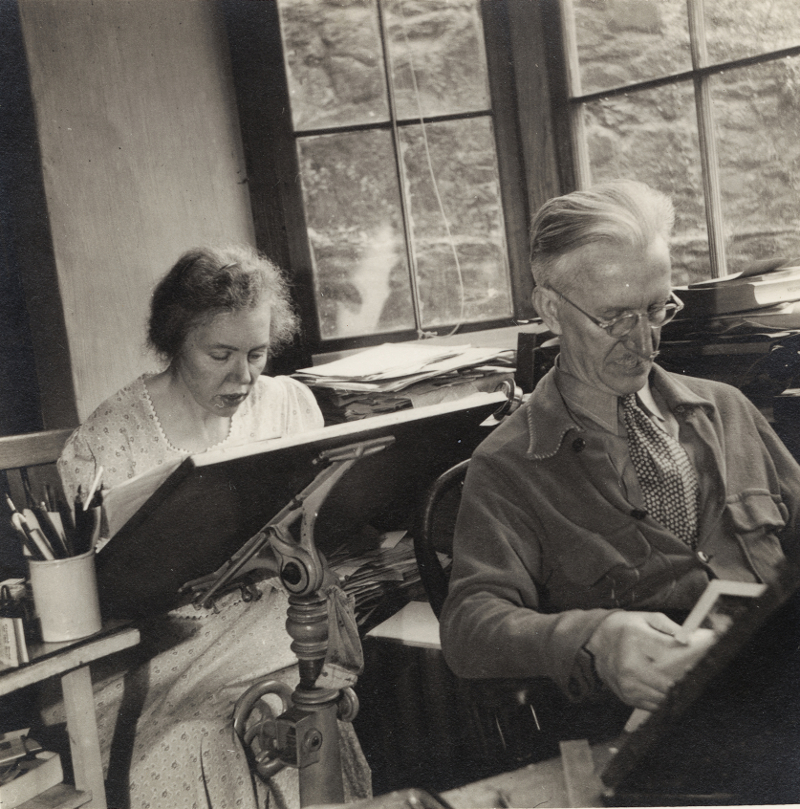

Berta and Elmer Hader in their studio in Nyack, NY (Courtesy of Concordia University)

Berta and Elmer Hader in their studio in Nyack, NY (Courtesy of Concordia University)