Did you know that Barnard College maintained a camp on Journey’s End Road from 1933 until 1991? Not I, even though I graduated from Barnard in 1987!

So, follow me back through time to learn more about this well-kept secret . . .

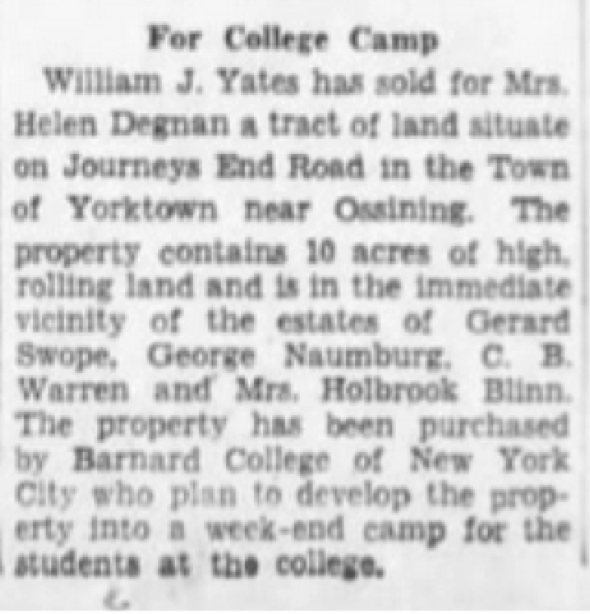

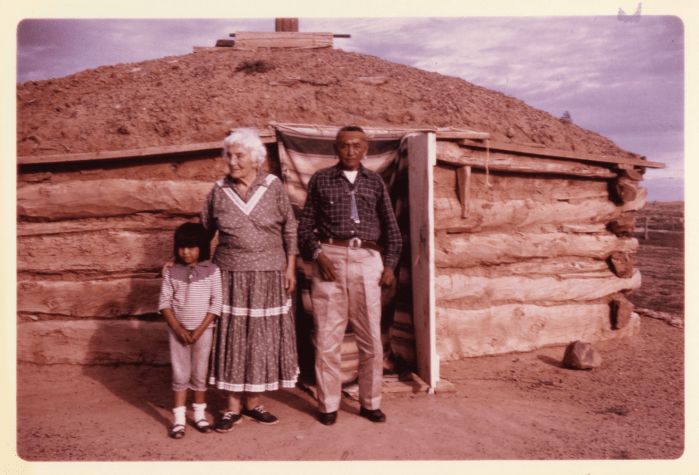

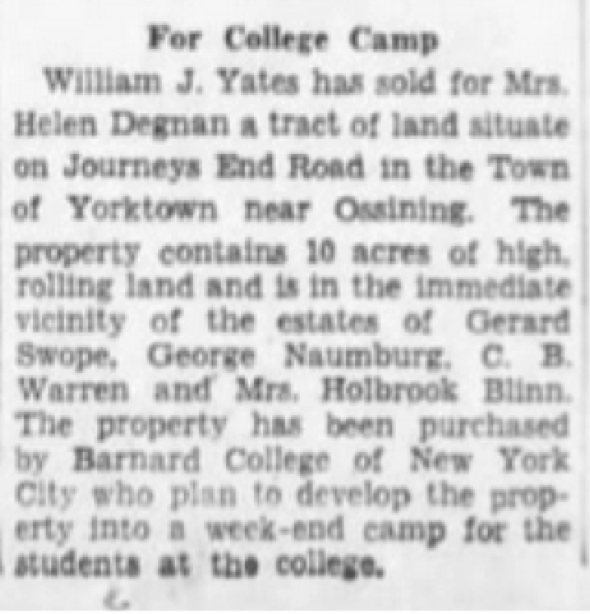

On February 19, 1933, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle ran this tiny story:

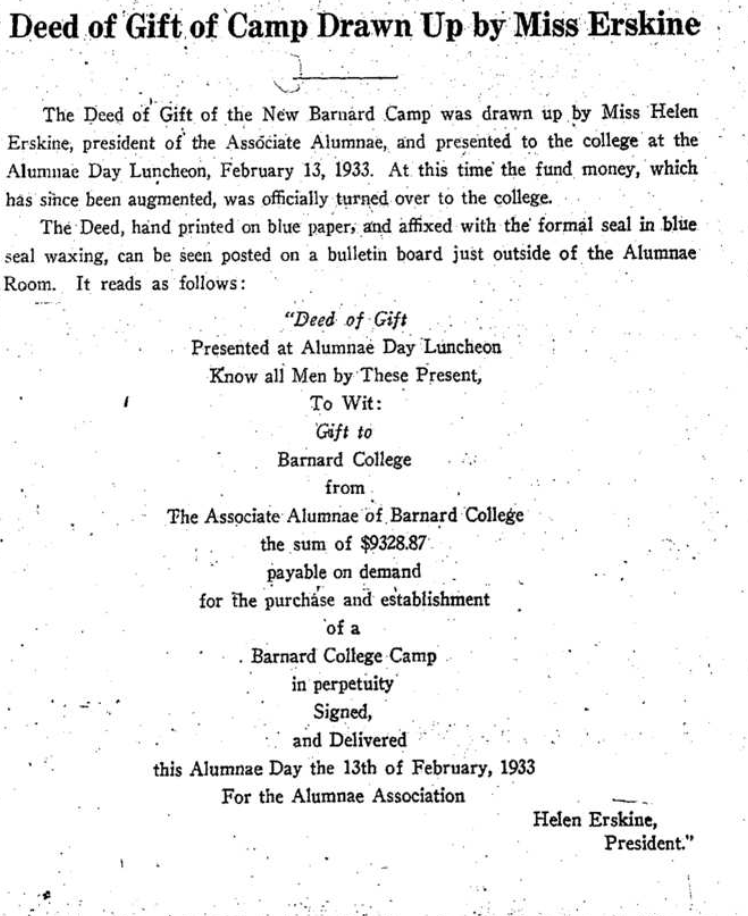

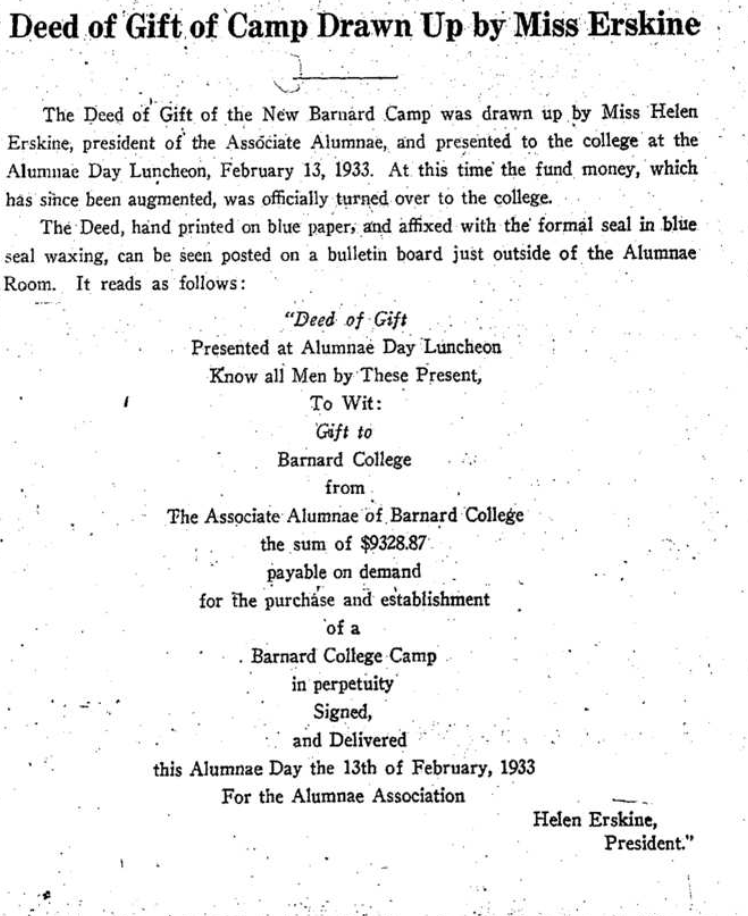

According to the Barnard College archive, the College was able to pay the Depression-era price of $9,000 for the above 10 acres of land thanks to a gift from the Alumnae Association:

(Snort! I love the boilerplate language above: “Know all men by these present . . .” Ha! It’s a women’s college, with money all coming from alumnae, presented at an alumnae luncheon! Oh English language, why so binary?)

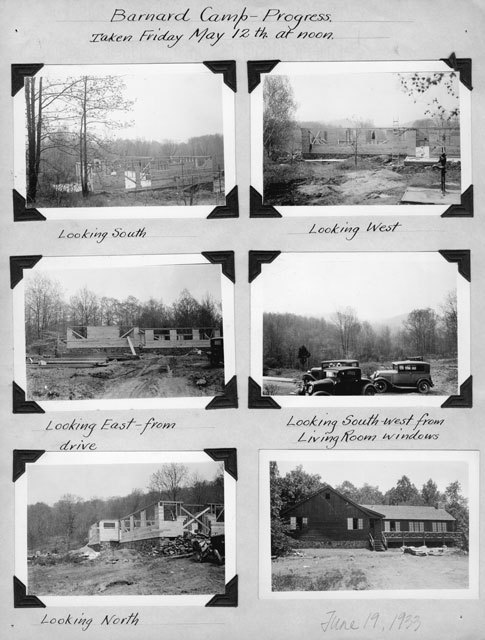

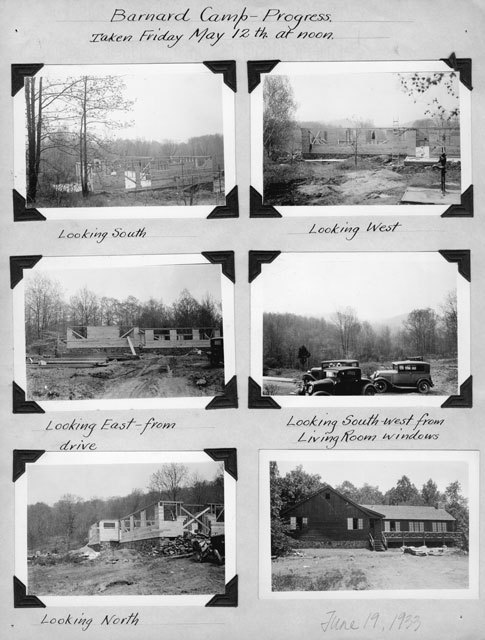

A simple log cabin was built by the Adirondack Log Cabin Company, and the camp officially opened on October 15, 1933.

Check out these cool photos of the cabin being built:

Able to sleep 10 – 15 students in two bunkrooms, everything about the camp was rustic in the extreme. The only heat came from wood stoves and a stone fireplace, with all firewood chopped by the students:

I did not expect this when I applied to Barnard!

and carried to the cabin:

Hey, winter is FUN!

All food was cooked by students over fire pits:

Mmm, Yum! I love squirrel

or on a stove that was probably old-fashioned even then:

Ooh, lovely, this kettle should be boiling in just under an hour!

Every drop of water was hauled by students from an outdoor pump:

Why am I always the one elected to do this?

And with no running water in the cabin, bathing took place in a nearby lake (when it wasn’t frozen, I assume,) and outhouses were the only waste facilities.

Sounds kind of delightful in the Spring and Fall, doesn’t it? However, these hardy Barnard women enjoyed the cabin year round!

Later on, three campsites with shelters were added for the truly stalwart who found the whole cabin experience too soft:

We don’t need no stinking walls!

We don’t need no stinking walls!

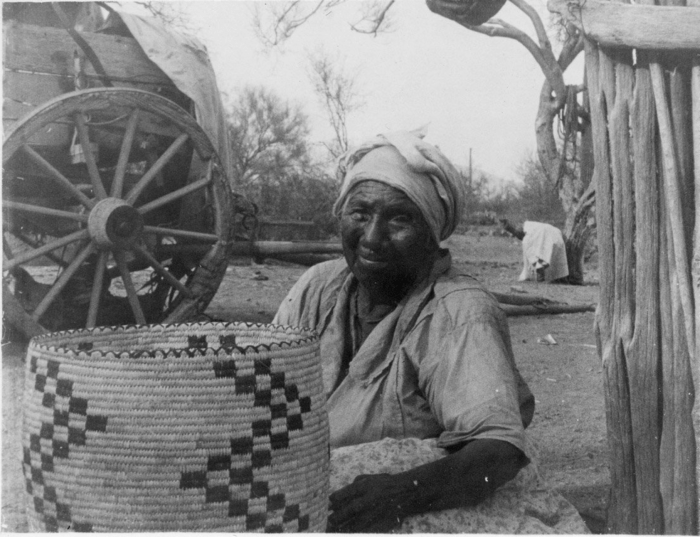

The Administration was thrilled with their new camp, the fruition of a ten-year quest.

(I could go on to document the previous incarnations of the Barnard Camp, which dated back to 1917 and World War I. With able-bodied men being sent overseas to fight, the shortage of male farm workers affected food production. So Dr. Ida Ogilvie, a Barnard geology professor, formed a chapter of the “Women’s Land Army” on her Bedford Hills farm. Barnard students, dubbed “Farmerettes,” spent weekends in the fresh country air tilling the soil and harvesting crops. Later, other outdoorsy weekend retreats were held at a farmhouse in Ossining, and at the Bear Mountain Inn. But I’ll stop here before your eyes completely glaze over.)

On Oct. 6, 1933, a special “Camp Supplement” issue of the school newspaper, the Barnard Bulletin, was published, which sang the praises of the new retreat: “Strangely and fittingly enough,” wrote Professor Agnes Wayman in the lead article, “The road that passes the property and ends at a private lake is called ‘Journey’s End,’ and so, the trail has led us to our journey’s end.”

How poetic!

Professor Wayman went on to say that “Camp now deliberately reaches out for the book-worm, the bridge fiend, the indoor girl, the weak sister…each may find friends and activities and peace and quiet and ‘unlax’ in her own way. Camp is the place for the student who wants a change from city life, for the student who wants to get away from It.”

The “bridge fiend?” In college? Goodness gracious me! Times have changed, no? And I’d hate to be a “weak sister” in that wood-chopping, water-carrying, outhouse-using milieu. But, still, doesn’t it look rather idyllic in the pictures? (Despite the possible squirrel-grilling.) In fact, I wouldn’t at all mind “unlaxing” there for only $5 a weekend!

Sadly, interest for the healthy outdoor life began to dwindle after World War II, and by 1961 a Barnard Camp Report noted that “Past reports have attempted to analyze the limited use of the camp. School pressures; absence of cohesive groups who socialize together; travel time, cost, and difficulty; lack of inside plumbing and adequate heating are valid explanations. The changing nature of the student, as several students have pointed out, accounts in part for their not participating in the experiences that the camp offers. Apparently few are interested in spending a weekend of group living with girls, especially when there are chores and some discomfort.”

Harumpf. Those soft baby boomers.

Because look how cozy it seemed:

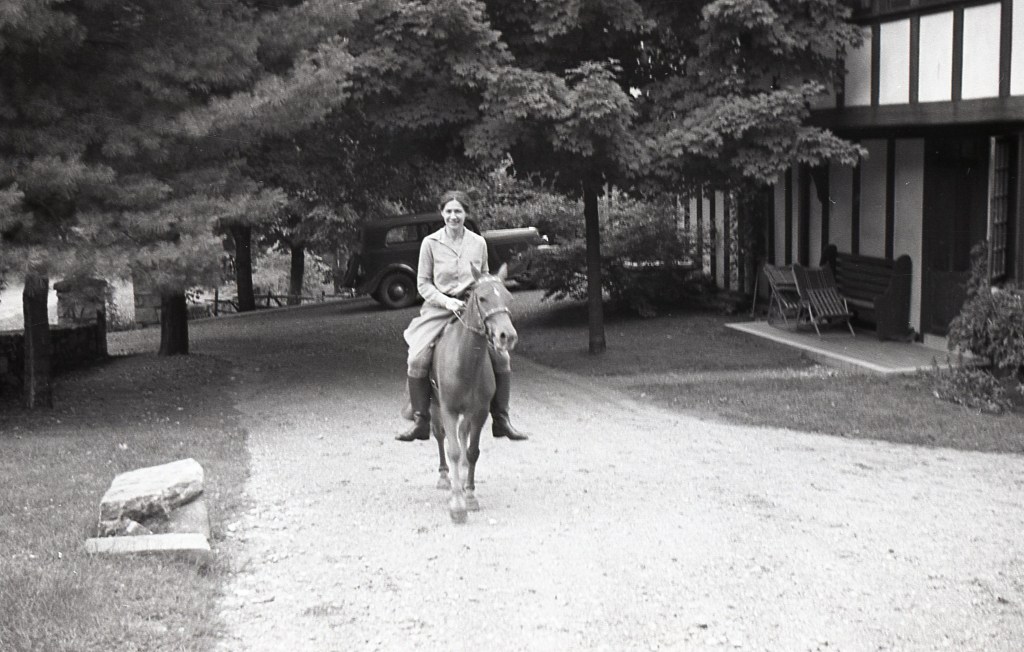

And see what fun they had!

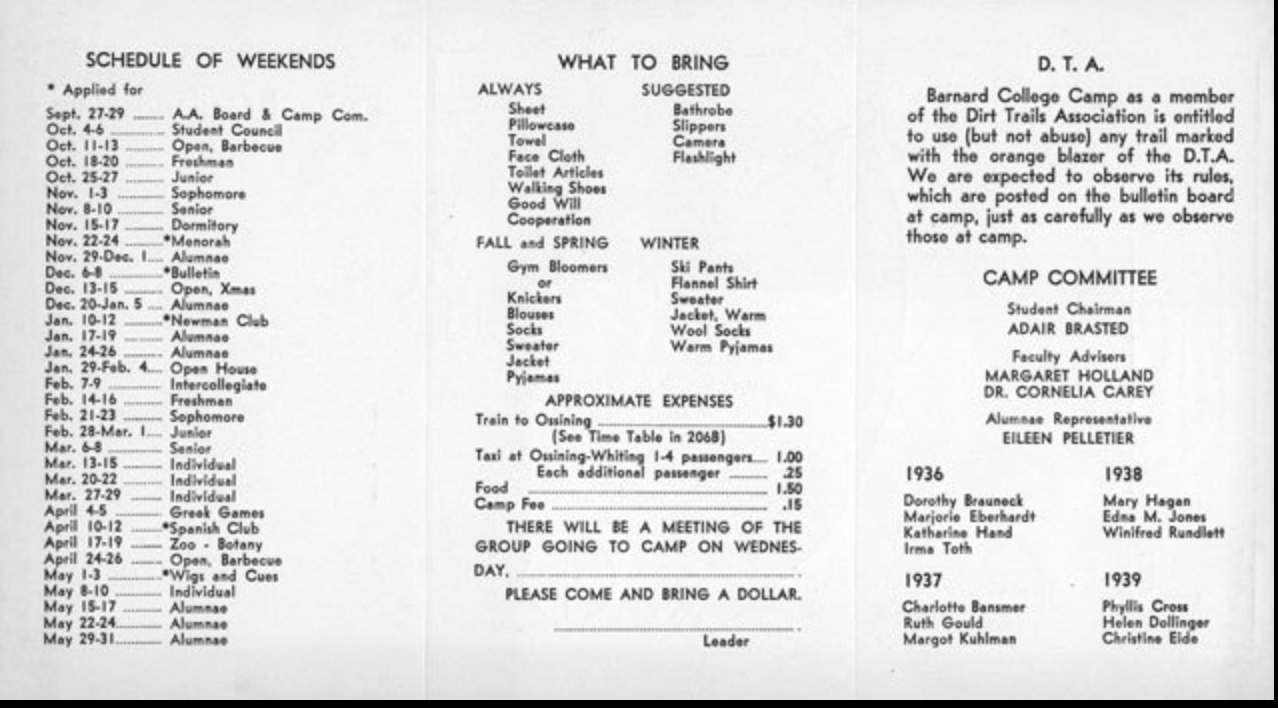

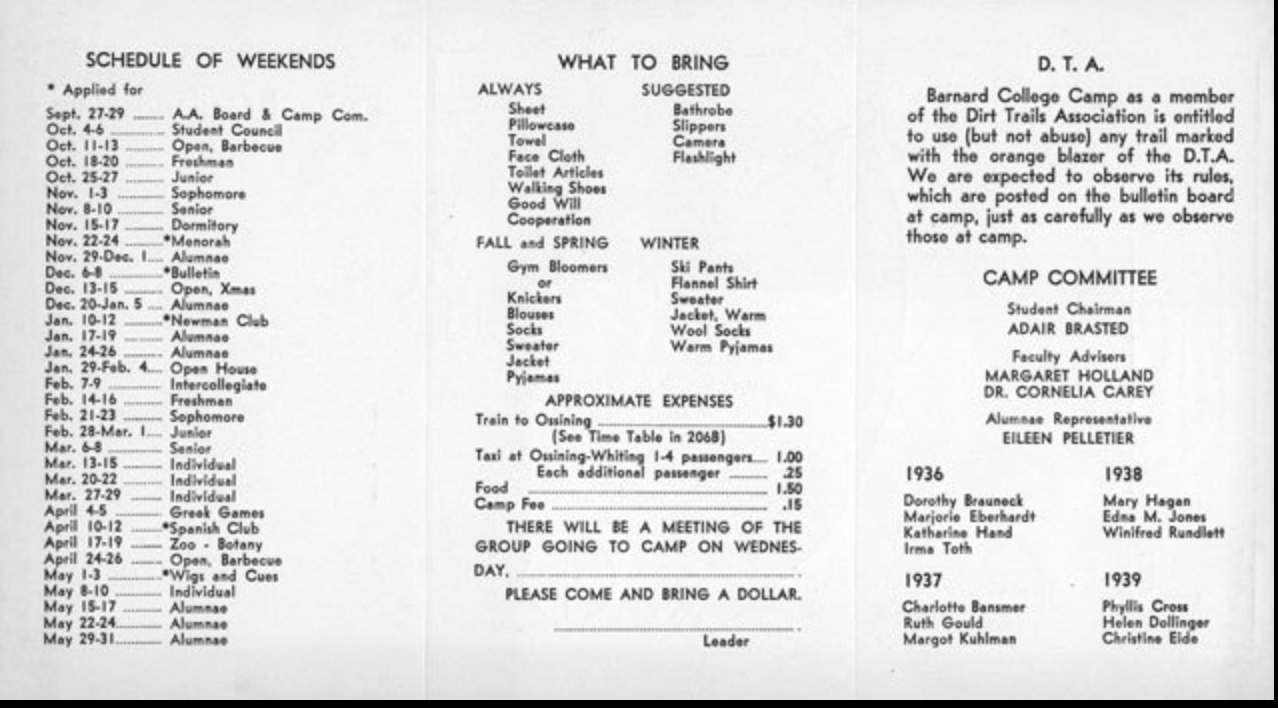

Can you believe it only cost $1.30 to take the train up to Ossining from NYC?

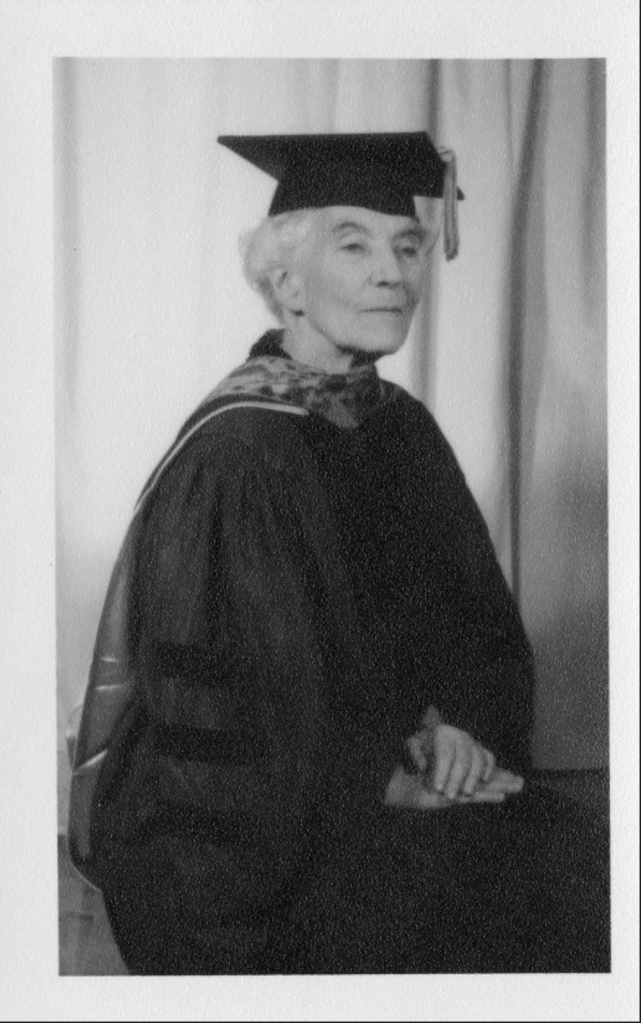

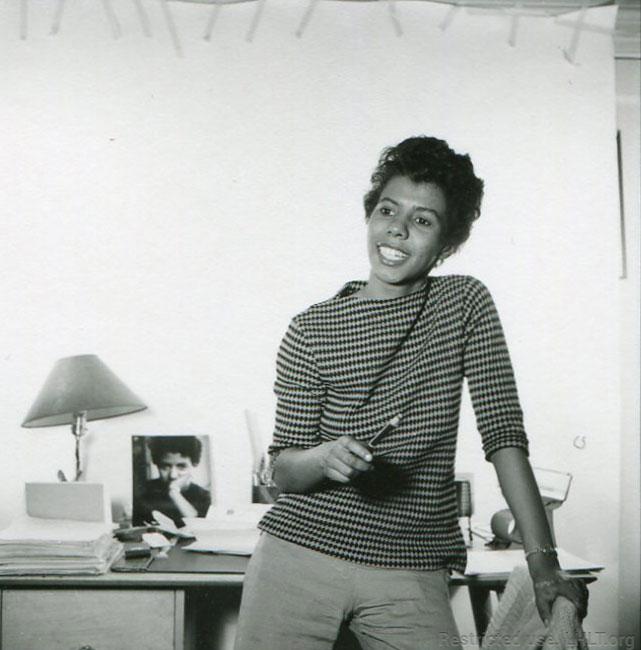

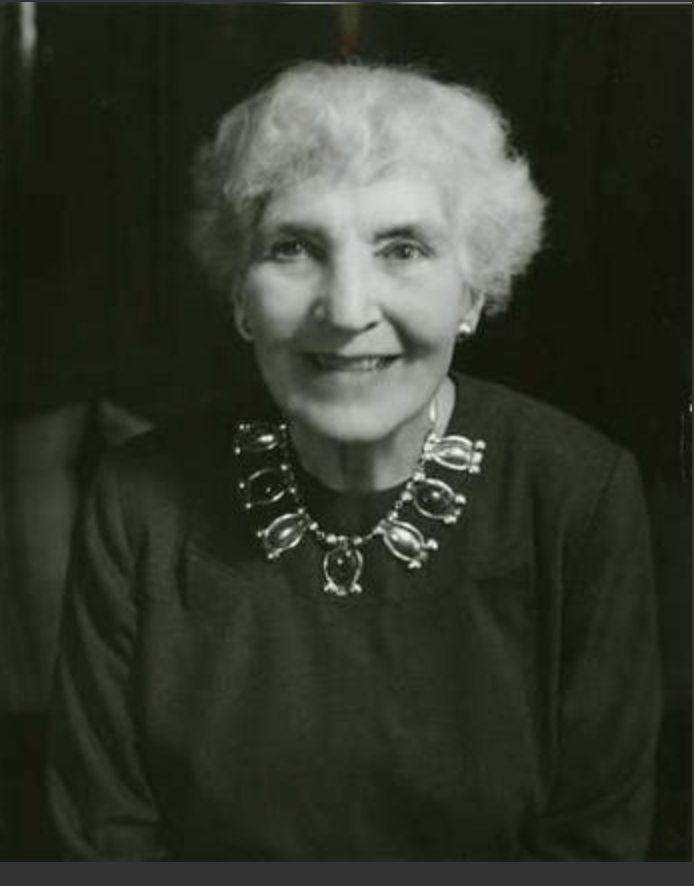

In December 1968, an editorial in the Barnard Bulletin bemoaned the fact that “People have lost their taste for the shared pleasures of fire-building and massive pancake breakfasts. Nowadays the cabin is less often visited than it was in the past, and large groups seldom get together there for a weekend. The times have changed, but, thank God, Holly House remains the same.” (The camp was renamed Holly House in 1963 at the retirement of Margaret Holland, the long-time Physical Education Department Chair and first camp counselor.)

The College kept the camp going for decades, mostly using it for retreats and alumnae events, although students were still supposedly allowed to go there. If they knew about it.

By 1991, student trips were no longer listed in the student handbook. (I swear, I never saw anything about the camp in my student handbook! Well, truthfully, I probably never read my student handbook. But still.)

The land was reportedly sold by the college in 1992 — so much for the “in perpetuity” of the existence of a Barnard College Camp. It kills me to think I could have visited the camp in its waning days! But, I confess, I’m not sure how much my well-coddled, 18-year old self would have appreciated bathing in a lake or using an outhouse.

So, file the above under history I’ve run by for years but never knew about until now.

You’re welcome.

All photos from the Barnard Archives and Special Collections

We don’t need no stinking walls!

We don’t need no stinking walls!