Jeanne Eagels

1890 – 1929

Broadway and early film star

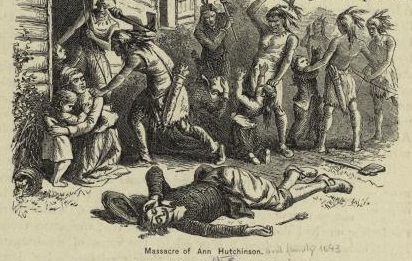

***Local Connection: Homes on Kitchawan Road (Rt. 134) and Cedar Lane***

Okay, first, if you are under the age of 95, you might ask, who is Jeanne Eagels?

Well, she was a big Broadway and film star in the 1910s and ‘20s — in fact, one of the biggest.

And her Ossining connection is that she owned not one, but two estates here: a 30-acre estate called “Kringejan” at 1395 Kitchawan Road, and 22-acres of land and a house on Cedar Lane Road.

In fact, I’m convinced that these two photos below were taken in the gardens of Kringejan:

Photographs by Maurice Goldberg for Vanity Fair, c. 1925

Public Domain

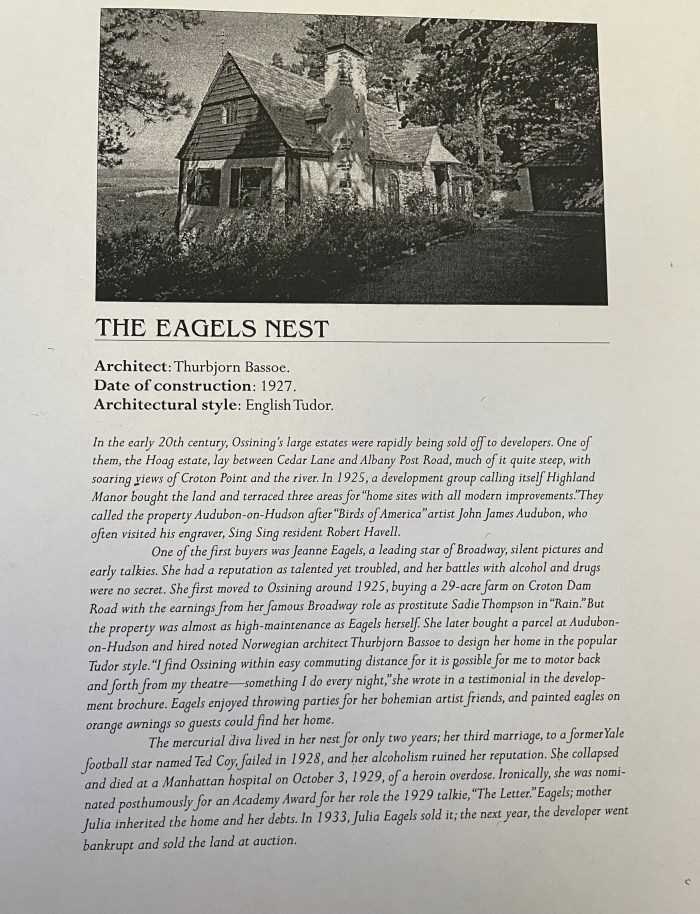

And here’s a description of her 2nd home in Ossining, on Cedar Lane Road:

In those days, Ossining was quite the place for the gentry to land – businessmen, bankers, writers and actors were snapping up farms and transforming them into elegant country estates. According to Eric Woodard and Tara Hanks in their biography Jeanne Eagels: A Life Revealed, Eagels fell in love with the Ossining area when she was making silent films at Thanhouser Studios in New Rochelle.

Hers was the classic “lift yourself up by your bootstraps” story that America loves: the small-town girl who comes to the big city and makes good. She started by nabbing bit parts in around 1908, and by dint of hard work, talent and luck, reached the top of her profession before her untimely death at the age of 39.

1924 found her on a list with Rockefellers, Roosevelts, Guggenheims and Harrimans when the income tax payments of Manhattan’s wealthiest were made public.

But somehow, that’s not at all how she’s remembered.

She lived most of her life on that tricky front line where she was applauded for her success while at the same time condemned for it. She was raised up and then torn down time and time again. The insatiable curiosity of the press and the public transformed almost every detail of her life into something salacious.

So, let’s try to separate the fact from fiction and give this accomplished woman her due.

Jeanne Eagels was born Amelia Eugenia Eagles in Kansas City, Missouri in 1890.

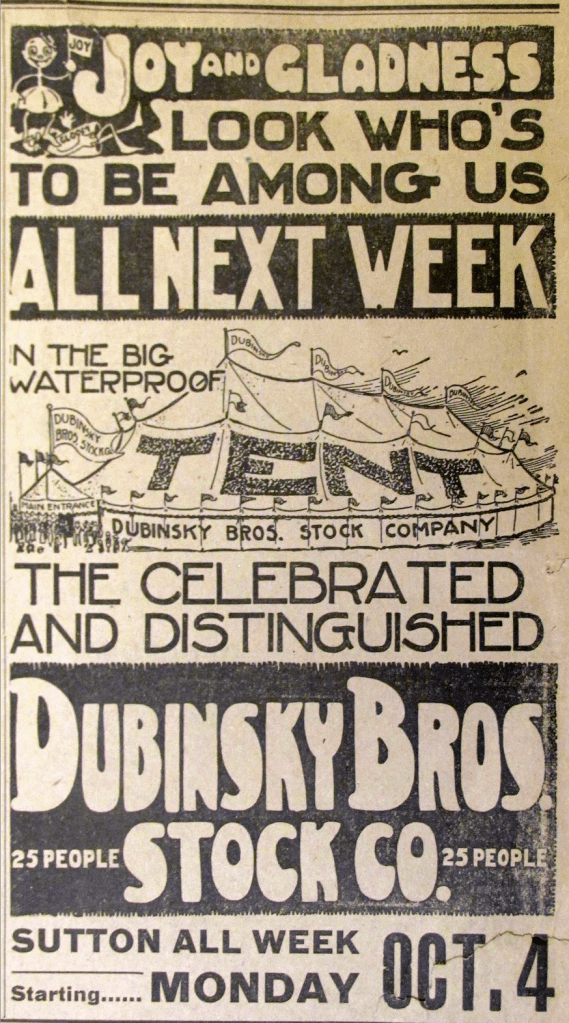

The story goes that Jean Eagles [sic] ran off with the Dubinsky Brothers Stock Company at the age of 15 (though she was really 18.) Starting off with a few small parts (and possibly by marrying one of the Dubinsky brothers) she clawed her way to the top there. At the time, stock companies were how most people living outside cities got their entertainment in the years before film and radio. And also how many actors got their starts.

These companies were constantly touring, often doing one night stands, after which the company would sleep sitting upright on chilly trains as they overnighted to the next stop. They played all sorts of venues, from legitimate theaters to church basements to tents in the nicer weather. On the rare occasion they played more than one night in a particular town, there were limitations about where they could stay because many hotels wouldn’t rent rooms to actors due to their supposedly loose morals. (And maybe because more than one had skipped out without paying.)

She left the Dubinsky Brothers in 1910 (and changed her name to Jeanne Eagels) to join a tour of Jumpin’ Jupiter, landing on Broadway for three weeks in March of 1911. While the show was savaged by critics, Eagels managed to land on her feet and score a job in the chorus of The Pink Lady, a Klaw & Erlanger production.

Courtesy of the New York Public Library – Billy Rose Theater Division

From here on, she’d continue to work steadily and for the most influential producers on Broadway, such as Charles Frohman, David Belasco, and the Shubert brothers.

Arguably, her most famous role was as Sadie Thompson in the play Rain. Whether you know it or not, I can guarantee you’ve heard of it somehow, or at least of the character of Sadie. Based on what was at the time considered a wicked and immoral story by Somerset Maugham (written in 1921), it’s about a prostitute named Sadie Thompson and the married missionary who falls in love with her as he tries to save her soul. It was provocative, controversial and just downright shocking.

Audiences couldn’t get enough of it.

Rain first premiered on Broadway in 1923. Lee Strasberg, the father of Method Acting, called her Sadie “One of the great performances of my theater-going experience . . . An inner, almost mystic flame engulfed Eagels and it seemed as if she had been brought up to some new dimension of being.”

(Fun fact: Gloria Swanson sold her Croton-on-Hudson estate to finance the 1928 silent picture version of Rain called Sadie Thompson, which she produced and starred in. Other actors connected to Rain in later films include Joan Crawford and Rita Hayworth. And, in 2016, the Old Globe Theater in San Diego premiered a musical version also called Rain. It’s a story that continues to fascinate.)

Jeanne Eagels quickly became as big a star as you could be back then. She appeared on Broadway and took her shows on the road, often selling out when she was the star. The Cleveland News ran a story about her which noted her “Lightning energy . . . Eyes snap. Voice trills. She seizes the attention.” It goes on to praise her realism and emotionalism – attributes it seems that most actresses of the time lacked.

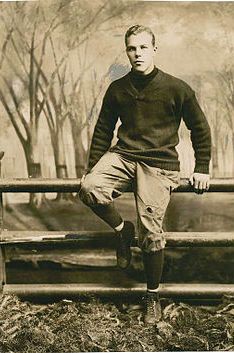

In 1925, Eagels secretly married Ted Coy, a famed Yale football player and supposedly the inspiration for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s character of Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby.

Ted Coy, legendary Yale football star.

But Eagels didn’t allow marriage to slow down her career. She stayed on tour with Rain until 1926, when she left to take on the role of Roxie Hart in the Maurine Dallas Watkins-penned play Chicago (in 1975, John Kander, Fred Ebb and Bob Fosse would turn it into a hit musical.) But as her star continued to ascend, her marriage with Coy became more and more volatile.

It’s at this point of her career that the legend of her temperamental nature becomes the story. Soon, the papers were running article after article about her failing marriage, health problems, mental instability and whispers of drug addictions. Ultimately, they got the better of her, and she quit Chicago.

After spending a few months in Ossining recuperating and trying to repair her marriage, she signed on to star in the play Her Cardboard Lover opposite a young Leslie Howard. Directed by an early-in-his-career George Cukor, and with a script doctored by P.G. Wodehouse, it seemed destined for success. Alas, Eagels’ reviews paled next to Leslie Howard’s.

Thus began a series of missed performances and general incidences of unprofessional behavior.

Here’s an excerpt from an article in the Milwaukee Sentinel from May 6, 1928, during the tour of Her Cardboard Lover:

Miss Eagel’s eccentricities are of long standing. Before each performance, the company and management wait anxiously to see if she will appear at all. When she does, nobody knows what she will do on the stage, and the stage manager stands ready to ring down the curtain in case of trouble.

The article goes on to describe how she simply disappeared when the show moved from Chicago to Milwaukee:

Days passed, the theatre remained dark, the company idle, the management began to tear its hair, already made gray by the erratic star. Towards the end of the week, the lady of mystery turned up with the simple explanation that “She hadn’t been feeling well.” It was too late to do anything in Milwaukee, but there was a fine advance in St. Louis. So the manager bought flowers for the star and the company took turns petting and pitying her and asking no questions.

But the newly formed Actors’ Equity Association (of which Eagels, along with her New Castle neighbor Holbrook Blinn, had been unsupportive and initially refused to join) brought her up on charges for her behavior, levied a $3,600 fine equal to two weeks’ salary (or $48,000 in 2025 dollars) and banned her from appearing on the Broadway stage for a year.

In response, Eagels just went off and made films because she could. She had made some silent movies before her stage career took off, and film producers had never stopped clamoring for her.

However, her personal demons were taking over, and after missing two weeks of shooting, she was fired from MGM’s Man, Woman and Sin, a silent film in which she was co-starring with John Gilbert. (Since she’s in the final cut, it seems like most of her scenes had been shot.) It’s also around this time the gossip columns start calling her “Gin Eagels” because she was known to drink hot gin “prescribed by her doctor to relieve persistent neuralgia.” (Let’s not forget, this is all during Prohibition.)

For the last year of her life, most of her press mentions concern her health (many hospitalizations), her divorce (in lurid detail), and her films. And, of course her tragic death.

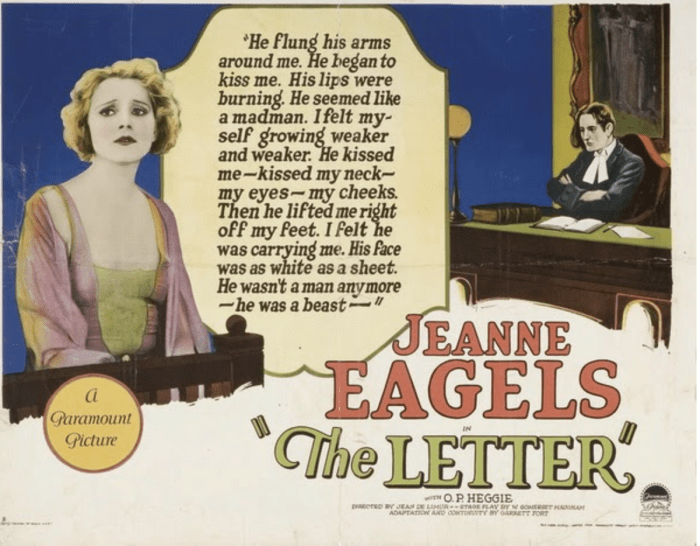

Her last project was a 1928 film called The Letter. It’s her only talkie, and she was posthumously nominated for a Best Actress Oscar Award for her performance (it went to Mary Pickford instead.)

Here’s a link to a scene. She does not look like she is at her best here.

Sadly, the story that’s mostly remembered is the tragedy of her early death, and her erratic behavior. This was helped along by a titillating biography written in 1930 by a muckraking Chicago reporter, Edward Doherty. Called The Rain Girl: The Tragic Story of Jeanne Eagels, her death was attributed to heroin addiction and alcoholism.

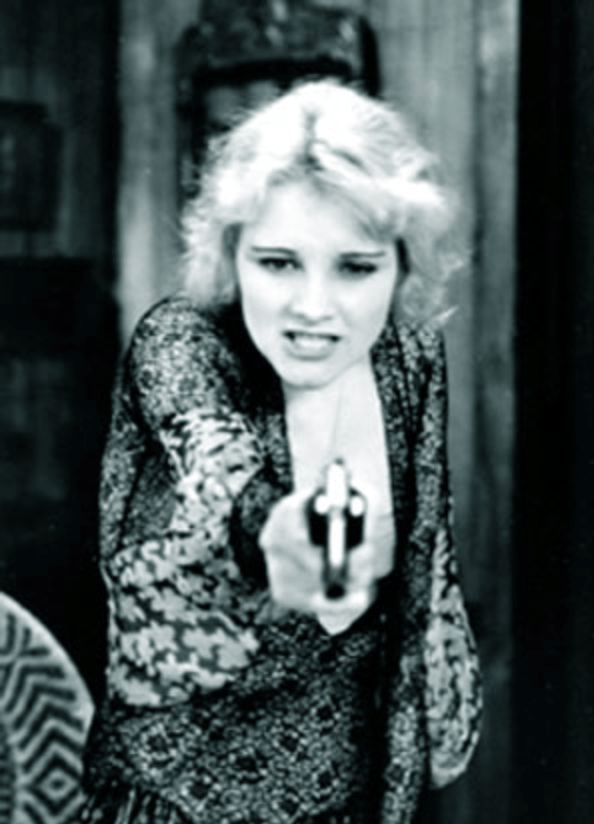

Eagels’ story was still bankable in 1957 when Columbia Pictures produced a highly fabricated biopic based on the Doherty book, starring Kim Novak:

Even the New York Times was not immune to capitalizing on her death. Her 1929 obituary made sure to remind everyone of her volatility and instability. It even took the time to follow up on her cause of death, publishing an article several days later that quoted the City Toxicologist’s finding that she “died from an overdose of chloral hydrate, a nerve sedative and soporific.”

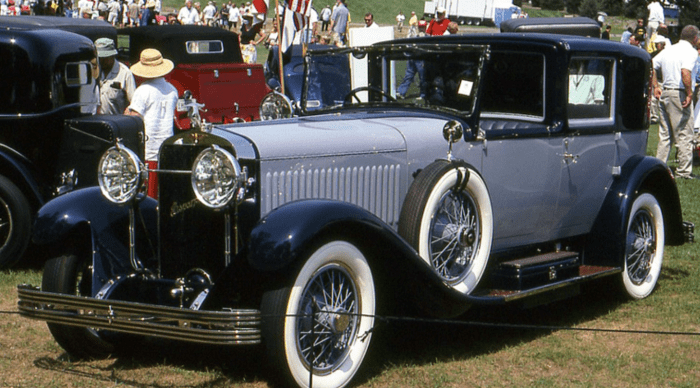

The Times would go on to cover her funeral, burial and the settlement of her estate, noting that it totaled over $88,000 (that’s $1.1 million today) and consisted of her Ossining home, nearly $12,000 in jewelry and furs, and a rare Hispano-Suiza autocar.

A 1927 Hispano-Suiza motorcar. Imagine living in Ossining when cars like that were on the road! Today such cars can sell for up to $450,000

Clearly she was troubled and likely an addict of some kind, and I’m not trying to be an apologist here for the unprofessional behavior reported by the press at the time. The fact of the matter is that she was a remarkably successful actress, and producers kept hiring her because she sold tickets and made money for them. Looking at her films today, it might be hard to see the appeal, but back then, she was the cat’s meow.

Looking back along the trail

Looking back along the trail