Come on down to the Ossining Public Library at 2pm on Saturday, February 21, 2026 and get your (signed if you want!) copy of Ossining’s newest history book.

Come on down to the Ossining Public Library at 2pm on Saturday, February 21, 2026 and get your (signed if you want!) copy of Ossining’s newest history book.

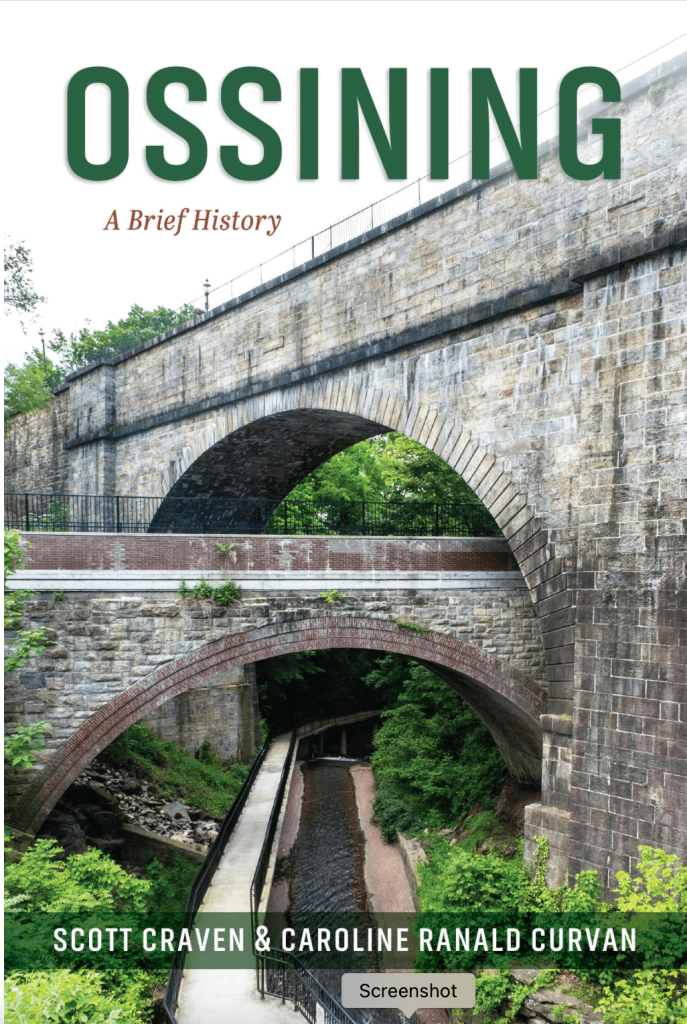

It’s almost here! Our new book, Ossining: A Brief History, will be released on February 10, 2026. Here’s a sneak peek at the cover — what do you think?

Check out the publisher’s website here to pre-order, or visit your favorite brick and mortar bookshop after its release.

We’ll be doing an official book launch at the Ossining Public Library on Saturday, February 21, 2026 at 2pm — watch this space for more info on that and other events coming your way soon!

Folks, this is just a short post to direct you to the Sing Sing Prison Museum website where you can learn more about the history of this iconic penitentiary, as well as read three posts I recently wrote for their blog about religion in Sing Sing Prison.

[Note that the Museum is on track to open very soon, and in the meantime is offering numerous events to the public as they complete construction on their space in Ossining’s historic Olive Opera House.]

2. Chaplains of Sing Sing – Mr. Gerrish Barrett, Sing Sing’s First Prison Chaplain

3. The Fight for Sing Sing’s Soul – The Tenure of Reverend John Luckey, 1839-1865

Welcome to the virtual exhibit page for Ossining Women’s History Month 2025!

While the installation at the Ossining Public Library (53 Croton Avenue) is no longer on display, the entire exhibit will live on this blog in perpetuity.

Who are these women?

These are all remarkable women local to Ossining who made a big impact in shaping our community and our world. Some are national figures. Some have local streets, schools or parks named after them. And some just did their work quietly. But all have accomplishments that deserve to be recognized and shared.

What will you see?

This is a retooling and enlargement of last year’s exhibit presented at the Bethany Arts Community, with expanded biographies and four more fascinating women included.

These women represent all facets of American life – art, religion, science, politics, military service, activism, and philanthropy. Those with a higher profile in life offer more images and material. Others avoided the limelight (either on purpose or through circumstance) and less is known about them, but this exhibit will help uncover and celebrate all of their remarkable stories.

To learn more about each woman featured, simply click on their names below and you’ll be quickly directed to a page with their detailed biography, including photos and links to further enrich their extraordinary stories.

Enjoy!

Caroline Ranald Curvan

Ossining Town Historian & Exhibit Curator

Before you go . . .

Help me curate Women’s History Month 2026!

I’d like to add to this group of Local Legends by crowd-sourcing nominations for next year’s Women’s History Month exhibit.

Who would you like to see honored and why? (They should be women who have some connection to the Ossining area . . .)

You can either fill out this brief form online or complete a hard copy at Ossining Library (downstairs in the exhibit gallery.)

Eliza Wood Farnham

1815 – 1864

Writer

Activist

Abolitionist

Prison reformer

***Local Connection: Matron of Mt. Pleasant Women’s Prison (aka Sing Sing Prison)***

In a society that portrayed the ideal woman as submissive, pure, and fragile, Eliza W. Farnham created her own concepts of female identity. Her theories and actions, occasionally contradictory, offered alternatives to women who felt confined by the limited roles prescribed by their culture. As Catherine M. Sedgwick, a contemporary writer and friend wrote of her “She has physical strength and endurance, sound sense and philanthropy . . . [and] the nerves to explore alone the seven circles of Dante’s Hell.”

Born in Rensselaerville, New York, Eliza Burhans’s early childhood was marked by the death of her mother and abandonment by her father. Growing up with harsh foster parents, she became a self-sufficient, quiet autodidact, reading anything and everything she could get her hands on.

At 15, an uncle would retrieve her from the foster home, reunite her with her siblings and arrange for her to go to school. By 21, she had married an idealistic Illinois lawyer, Thomas Jefferson Farnham, and set off with him to explore the American West.

Eliza would have three sons in four years, though only one would survive childhood. Thomas and Eliza would write up their observations of the West — he would become a popular travel writer of the day, and she would publish her memoir, Life in Prairie Land, in 1846.

In 1840, the Farnhams returned east and settled near Poughkeepsie, New York, where Eliza became deeply involved in the intellectual and reform movements of the day. An early feminist who believed that women were superior to men, Eliza wrote articles in local magazines against women’s suffrage, believing that women could have a much greater impact as mothers and decision makers in the home. (However, in their 1887 History of Woman Suffrage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony would write that Eliza’s attitudes evolved and that she ultimately saw the necessity of and supported women’s suffrage.)

Eliza also became interested in prison reform at the time, and in 1844 sought and was appointed to the position of Matron of the Mt. Pleasant Female Prison, at the time infamous for its chaos, rioting and escapes, to prove that kindness was a more effective method of governance than brutality.

She instituted daily schooling in the prison chapel and started a small library that allowed each woman to take a book to her cell to read (making sure that there were picture books available for those who couldn’t read.) She also believed that lightness and cheer were more conducive to reformation, and placed flowerpots on all windowsills, tacked maps and pictures on the walls, and installed bright lights throughout. She spearheaded the celebration of holidays, introduced music into the prison, and began a program of positive incentive over punishment. Finally, she fought to improve the food served to the women and ended the “rule of silence”, believing that “the nearer the condition of the convict, while in prison, approximates the natural and true condition in which he should live, the more perfect will be its reformatory influence over his character.” [1]

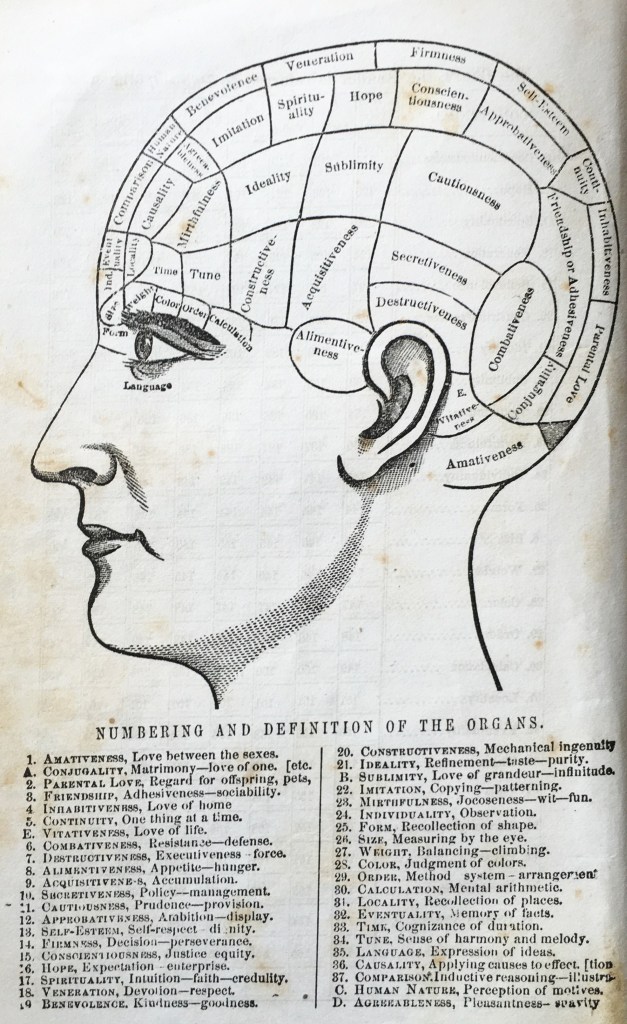

It must be said that her methods were deeply influenced by the now-discounted “science” of phrenology which looked at the correlation between skull shape and human behavior, giving a biological basis for criminal behavior (not, as many religious people believed then, sheer, incorrigible sinfulness.) Eliza would even edit and publish an American edition of a treatise by the English phrenologist Marmaduke Blake Sampson, under the title Rationale of Crime and its Appropriate Treatment. [2]

Although the mayhem that had plagued previous matrons was significantly reduced, Eliza’s approach was viewed as simply coddling the prisoners. This led to conflicts with several staff members, including Reverend John Luckey, the influential prison chaplain. By 1848, a change in the political landscape installed new prison leadership and she was forced to resign.

She would move to Boston, to work at the Perkins Institute for the Blind until her explorer-husband died unexpectedly while in San Francisco. Eliza went to California both to settle his estate and execute a plan assisting destitute women purchase homes in the West to achieve financial independence. Though that initiative was not successful, Eliza herself bought a ranch in Santa Cruz County, built her own house, and traveled on horseback unchaperoned, among other scandalous things she would detail in her 1856 book California, In-doors and Out.

In 1852, she entered into a stormy marriage with William Fitzpatrick, a volatile pioneer. During this period, she had a daughter, who died in infancy, worked on her California book, taught school, visited San Quentin prison, and gave public lectures.

Divorcing Fitzpatrick in 1856, she returned to New York and began work on what is arguably her most significant work, Woman and Her Era. In it, she would glorify women’s reproductive role as a creative power second only to that of God. She further contended that the discrimination women experienced and the double-standard of social expectations stemmed from an unconscious realization that females had been “created for a higher and more refined existence than the male.”[3]

So, her initial disdain for women’s equality and suffrage stemmed from her unique feminist philosophy that ironically saw women as superior due to their reproductive function, historically something that had always defined female inferiority. Thus, in her world view, why should women lower themselves to the level of men to achieve “equality”?

It’s a fascinating way to look at the world, no?

Eliza would give numerous lectures on this topic before returning to California and serving as the Matron of the Female Department of the Stockton Insane Asylum.

In 1862, she would work towards a Constitutional Amendment to abolish slavery and, in 1863, answer the call for volunteers to help nurse wounded soldiers at Gettysburg.

She died of consumption a year later, likely contracted during her Civil War hospital work.

She is buried in a Quaker cemetery in Milton, New York.

Major Publications:

Life in the Prairie Land (1846) A memoir of her time on the Illinois prairie between 1836 and 1840.

California, In-doors and Out (1856) – A chronicle of her experiences and observations in California.

My Early Days (1859) An autobiographical novel describing Farnham’s life as a foster child in a home where she was treated as a household drudge and denied the benefits of a formal education. The fictional heroine reflects Farnham’s own character as a tough, determined individual who works hard to achieve her goals, overcoming all obstacles.

Woman and Her Era (1864) Farnham’s “Organic, religious, esthetic, and historical” arguments for woman’s inherent superiority.

The Ideal Attained: being the story of two steadfast souls, and how they won their happiness and lost it not (1865) This novel’s heroine, Eleanora Bromfield, is an ideal, superior woman who tests and transforms the hero, Colonel Anderson, until he is a worthy mate who combines masculine strength with the nobility of womanhood and is ever ready to sacrifice himself to the needs of the feminine, maternal principle.

SOURCES

James, Edward T., et al., editors. Notable American Women, 1607-1950 : A Biographical Dictionary. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

Wilson, James Grant, et al., editors. Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography. D. Appleton & Co., 1900.

[1] NYS Senate Report, 70th Session, 1847, vol. viii, no.255, part 2, p. 62

[2]Notable American Women, 1607-1950 : A Biographical Dictionary.

[3] Farnham, Eliza W. Woman and Her Era

Kathryn Stanley Lawes

1885-1937

“The Mother of Sing Sing”

***Local Connection: The Warden’s House, Spring Street***

(Today, the clubhouse of the Hudson Point Condominiums)

Kathryn Stanley Lawes (1885 – 1937) was known as the “Mother of Sing Sing.”

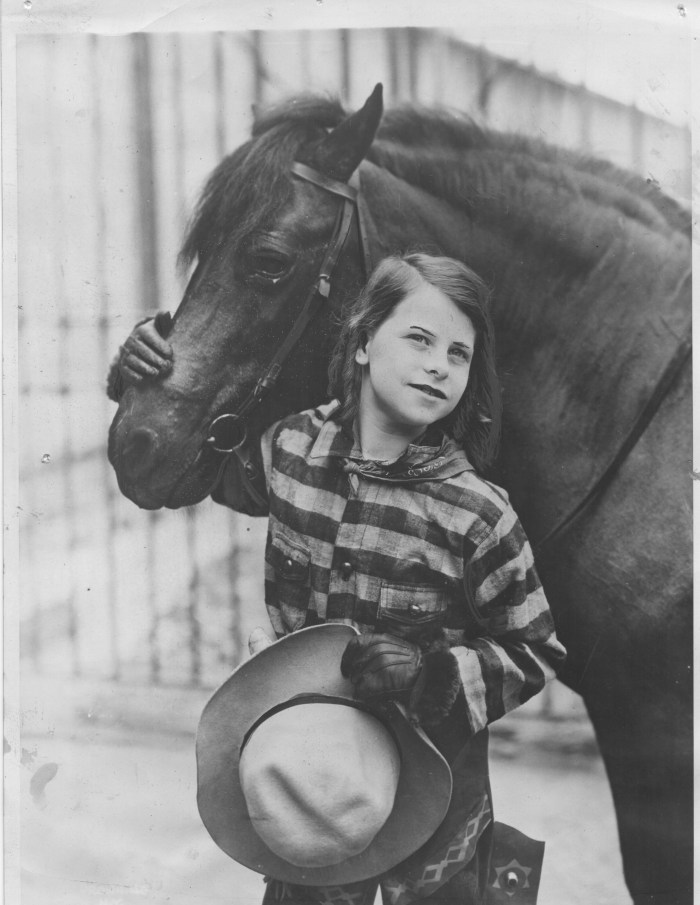

Wife of Warden Lewis Lawes, the longest tenured Prison Warden in Sing Sing’s history, she arrived at Sing Sing on January 1, 1920 with her two young daughters in tow. Settling into the drafty old Warden’s house situated next to the main cellblock, she would raise her girls (and have a third) within the walls of the prison.

She would regularly go into the prison and visit with the incarcerated. And her quiet kindnesses were the stuff of legend. She would arrange for every man to get a Christmas present – noting that some had never received one in their brutal lives. She would help them write letters to their families. Her youngest daughter, Cherie, recalled how her mother once gave away a favorite dress of hers so that the daughter of one of “the boys” could wear it to attend a high school dance.

Kathryn hosted Labor Day picnics for inmates, Halloween parties for the neighborhood children, and oversaw special meals in the mess for Thanksgiving and other holidays.

Those incarnated in Sing Sing knew that they could trust her, with one quoted as saying that telling her something was “like burying it at sea.”

In 1937, the Logansport-Pharos-Tribune wrote one of the very few articles about her, saying “When a convict’s mother or near relative was dying, the convict was permitted to leave the Sing Sing walls for a final visit. On such occasions, instead of going under heavy guard, he was taken in Mrs. Lawes’ own car, often accompanied by the Warden’s wife herself.”

She was especially solicitous to those awaiting execution, doing little things to make their cells brighter, spending hours talking to them – sometimes she would even arrange for their families to stay in the Warden’s house as the execution date drew near. She also made sure that every incarcerated man (and women) had a decent burial if they had no immediate family.

Little things, perhaps, but important.

Born in 1885 in Elmira, New York, Kathryn Stanley was ambitious and smart. At 17, she took a business course and landed a job as a secretary in a paper company. It’s around that time she met Lewis Lawes, who was working as an errand boy in a neighboring office.

But Lewis’ father was a “prison guard” (today the term is “Corrections Officer”) at the Elmira Prison, so it was rather natural that his son would eventually follow in his footsteps.

Kathryn and Lewis married in 1905 and started their family. Lewis quickly rose through the ranks in the New York prison system first in Elmira, then in Auburn. In 1915, he became Chief Overseer at the Hart Island reformatory, living right in the middle of the facility with Kathryn and their two infant daughters. Even then, Kathryn found time work with the boys in the reformatory, some who were as young as 10, giving many of them the first maternal attention they’d ever experienced.

Kathryn would be an essential participant in her husband’s success, helping cement his reputation as a progressive and compassionate Warden.

Still, it’s quite hard to flesh out Kathryn’s story. She gave very few interviews and those that she did give read like someone wrote them without ever talking to her. In fact, much of what we know about surfaced only after her mysterious death.

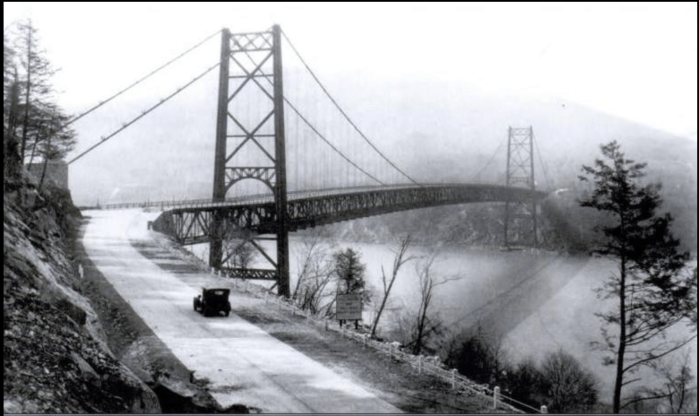

You see, one of the things that makes her story so complex and compelling is that she died at the age of 52 after falling off (or was it near?) the Bear Mountain Bridge.

A Mysterious Death

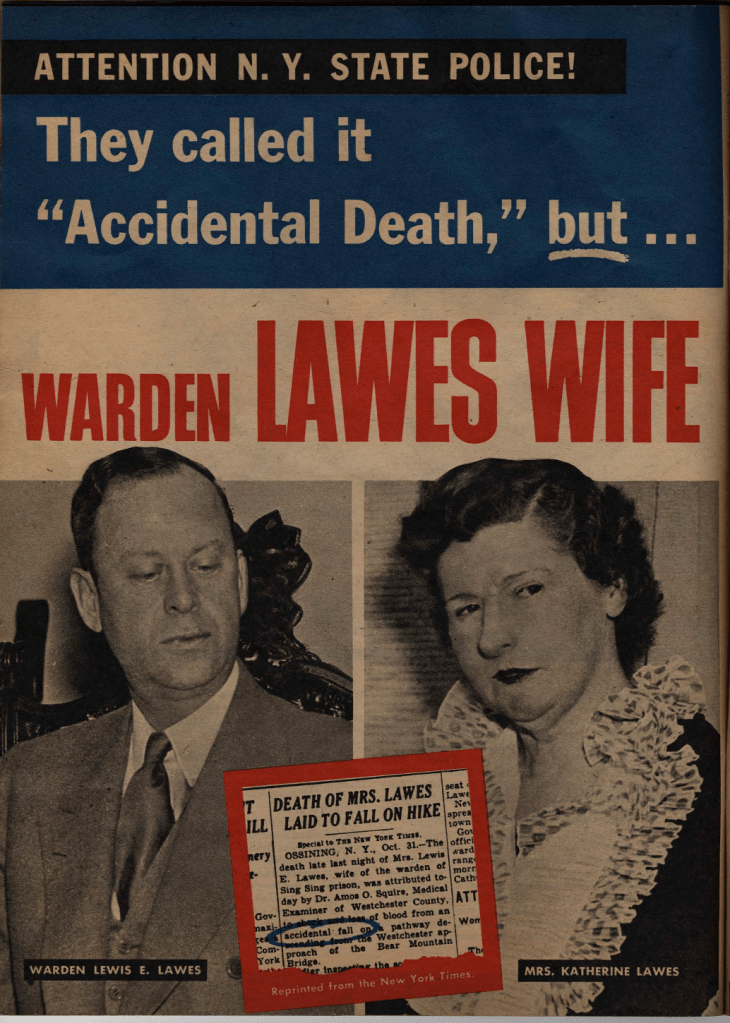

On October 30, 1937, the New York Times published an article entitled “Wife of Warden Lawes Dies After a Fall. Lies Injured all Day at Bear Mountain Span.” In it, the New York State Police stated that she had “jumped or fallen” from the bridge. Though conscious when discovered by Warden Lawes, their son-in-law, and Dr. Amos Squire, she died in Ossining Hospital soon after from her injuries.

A few days later, a follow-up story was published in the Times that quoted heavily from Dr. Squire (the former Sing Sing Prison Doctor as well as Westchester County Medical Examiner). Dr. Squire had apparently gone back to investigate the scene of the accident. There, according to the article, he found “her high-heeled shoes caught between two boards of a walk” and concluded that she had gone hiking, perhaps venturing down the trail to pick wildflowers. He continued, “After falling and breaking her right leg, Mrs. Lawes evidently dragged herself about 125 feet southward along the path to the pile of rock where she was found exhausted.”

The men of Sing Sing were devastated when they heard the news of her sudden and shocking death. Eventually, in response to their entreaties, the prison gates were opened and two hundred or so “old-timers” were permitted to march up the hill to the Warden’s house to pay their last respects at her bier.

(In 1938, the New York Times noted that the “Prisoners of Sing Sing Honor Late Mrs. Lawes” with the installation of brass memorial tablet, paid for by the Mutual Welfare League, a organization of incarcerated individuals.)

Kathryn’s Influence

Fifteen years after her tragic death, Kathryn Lawes’ story continued to capture the attention of the press.

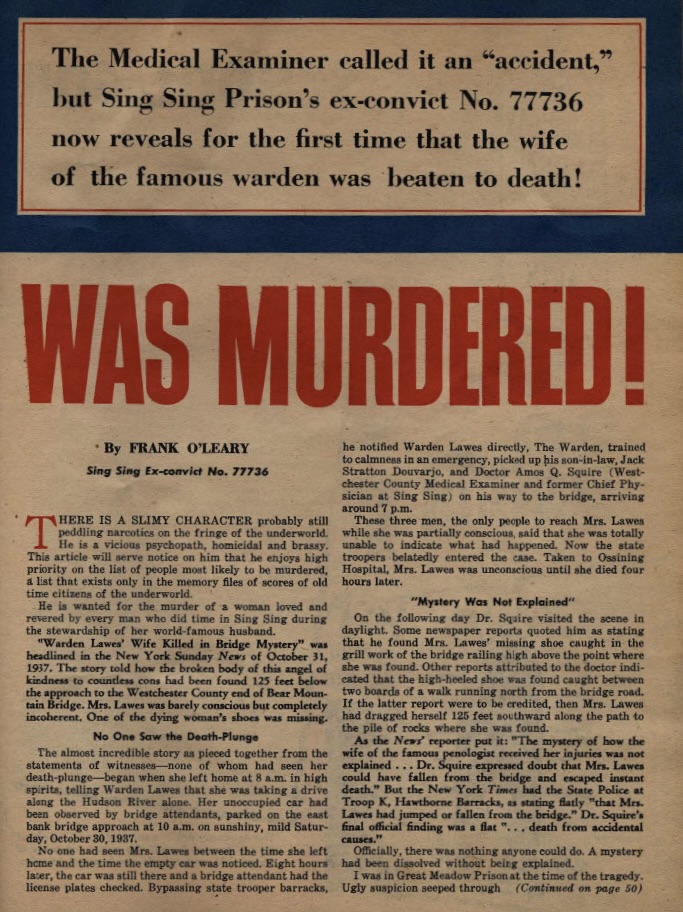

From a March 1953 feature in The Reader’s Digest “The Most Unforgettable Character I’ve Ever Met”, to the July 1956 exposé in tawdry Confidential Magazine below, Kathryn’s life (and death) remained compelling.

Even today, one can find sermons online that praise Kathryn Lawes’ generosity and compassion for those that society would rather forget.

Today’s post highlights the life and work of Kathryn Stanley Lawes, known as the “Mother of Sing Sing.”

Now, Kathryn Lawes’ story was actually my entry into Ossining history – when my husband and I first moved here, one of the first things we did was go to the Ossining Library and check out every book we could find about Ossining.

Of course, many of them were focused on Sing Sing Prison. Built by convicts in 1825 using stone quarried on site, it has featured prominently in the history and lore of our town. And Hollywood’s films of the 1930s, starring actors like Humphrey Bogart, Spencer Tracy, and Bette Davis, and where the terms “Up the River,” “The big house” and “The last mile” were coined, helped burnish the myth and mystery of the prison. (Fun fact: Many of these films were actually shot inside Sing Sing’s walls, using real prisoners as extras and sometimes engaging the actual Warden, Kathryn’s husband Lewis Lawes, to play a version of himself. In 1934, Warner Brothers even built a brand-new gymnasium for the prison as a thank-you. Here’s a partial list of films if you’re interested.)

One of the first books I read was Ralph Blumenthal’s “The Miracle at Sing Sing,” a biography of Kathryn’s husband, the progressive and once well-known Warden Lewis Lawes. In charge of Sing Sing from 1920 to 1941, he instituted many reforms and remains the longest tenured prison warden in its history. He also seems to have had the highest profile of any prison warden ever, appearing in movies, giving lectures world-wide, hosting his own radio program, writing books, articles, a Broadway play, and even a couple of screenplays. He also oversaw more executions than any other Sing Sing warden (303, to be precise, with four of them women.)

His wife, Kathryn, was beloved by Sing Sing’s inmates — to the point that they all called her “Mother.” In addition to raising three daughters inside the prison walls, she would regularly go into the prison and visit with the incarcerated. She arranged for every man to get a Christmas present; she would help them write letters to their families; she would even intercede on their behalf with the Warden on occasion.

In 1937, the Logansport-Pharos-Tribune wrote one of the few articles about her and described how she “Took – not sent – food and clothes and money to a family left desolate by the husband’s imprisonment. She saw to it that encouraging letters went to hopeless young criminals. Many, many dollars found their way from her purse to the pockets of newly released men, frightened to face freedom again. . . When a convict’s mother or near relative was dying, the convict was permitted to leave the Sing Sing walls for a final visit. On such occasions instead of going under heavy guard, he was taken in Mrs. Lawes’ own car, often accompanied by the Warden’s wife herself.” [1]

Her youngest daughter, Cherie, recalled how her mother once gave away a favorite dress of hers so that the daughter of one of “the boys” could wear it to attend a high school dance.

Kathryn hosted Labor Day picnics for inmates, Halloween parties for the neighborhood children, and made sure the mess served special meals for Thanksgiving and other holidays.

The inmates knew that they could trust her, with one quoted as saying that telling Mother Lawes something was “like burying it at sea.”

She was especially kind to those in the death house awaiting execution, quietly helping to make their cells brighter, spending hours talking to them, helping out their families – to the extent of putting the families up in her own home as the execution date drew near and arranging their final visits. She also made sure that every prisoner had a decent burial if they had no immediate family.

Little things, perhaps, but important. And so deeply compassionate.

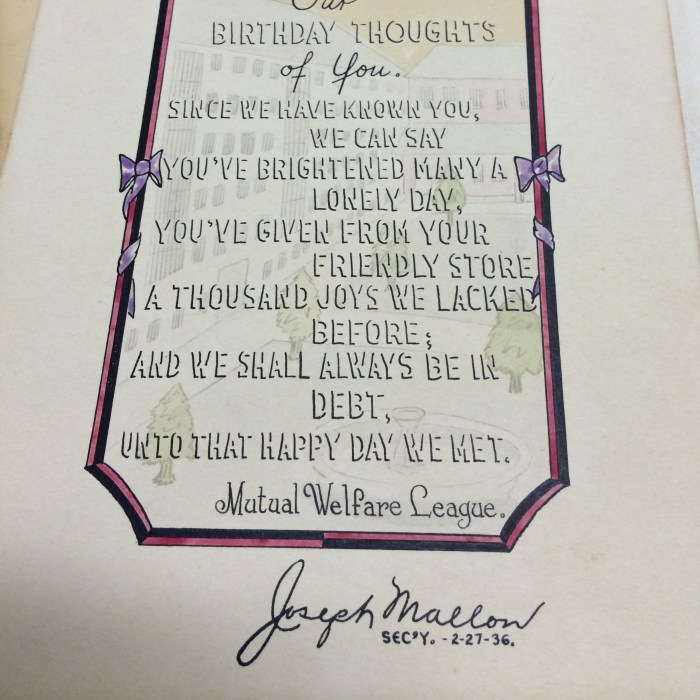

In 1936, the “boys” sent her this handmade birthday card:

Kathryn was born in Elmira, New York in 1885. Born into genteel poverty, she was ambitious and smart. At 17, she took a business course and landed a job as a secretary in a paper company. It’s around that time she met Lewis Lawes, who was working as an errand boy in a neighboring office. But Lewis’ father was a prison guard at the Elmira Prison, so it was rather natural that his son would follow in his footsteps.

Kathryn and Lewis married in 1905 and started their family. Lewis quickly rose through the ranks in the New York prison system first in Elmira, then in Auburn. In 1915, he became Chief Overseer at the Hart Island reformatory, living right in the middle of the facility with Kathryn and their two young daughters. There, Kathryn found time to work with the boys, some who were as young as 10, giving many of them the first maternal attention they’d ever experienced.

Still, it’s quite hard to flesh out Kathryn’s story. She gave very few interviews and those that she did give read like someone wrote them without ever talking to her. Much of what we know about her surfaced only after her mysterious death.

You see, what makes her story so complex (and dare I say compelling?) is that she died at the age of 52 after falling off the Bear Mountain Bridge.

What, you say? But yes, it’s true.

I hate to hijack a Women’s History month post with a true crime mystery, but it can’t be helped.

On October 30, 1937, the New York Times published an article entitled “Wife of Warden Lawes Dies After a Fall. Lies Injured all Day at Bear Mountain Span.” In it, the NYS Police said that she had jumped or fallen from the Bridge. Though conscious when discovered hours later by Warden Lawes, their son-in-law, and Dr. Amos Squire the Westchester County Medical Examiner, she died of her injuries soon after arriving at Ossining Hospital.

A few days later, a follow-up story was published in the Times that quoted heavily from Dr. Amos Squire (the former Sing Sing Prison Doctor as well as Medical Examiner), asserting that he had gone back to the scene of the accident. There, he found “her high-heeled shoes caught between two boards of a walk” and concluded that she had gone hiking, perhaps venturing down the trail to pick wildflowers. He surmised that she had tripped, rolled hundreds of feet down the steep embankment towards the river, breaking her leg in the fall. Then, he asserted, she dragged herself 125 feet to the spot where she was found twelve hours later.

I mean, really. So many things here –

First, how perfectly horrible. What a ghastly way to die. How could this have happened to such a universally beloved woman?

But then, the mind starts to whir . . . Were fifty-two-year-old women in the habit of hiking in 1937? In high heels? And how convenient that her high heels remained stuck between “boards of a walk.” And what about this dragging herself one hundred twenty-five feet southward with a compound fracture to spot where she was finally found? Finally, was it coincidence that the Westchester County Medical Examiner was Dr. Amos Squire, the former Sing Sing prison doctor and old friend to the Lawes’?

There’s so much to unpack. But I’m going to leave it there, for another time.

I’d rather try to concentrate on her life and the good she did in her relatively short time on earth by sharing some of the condolence letters Warden Lawes received. [2] More than anything, they give us a picture of the truly kind, benevolent influence she had on the lives of so many:

Joe Moran, Prisoner # 47-342 wrote “With the passing of dear Mrs. Lawes, the only ray of sunshine ever to be found within the walls of Sing Sing has gone forever. She lent courage to the condemned, she comforted the sick and she brightened the lives of the friendless. The men branded with numbers shall never forget the many kindnesses and acts of charity administered to them by the woman they regarded as their mother.”

Edward McIntyre, a former inmate, said “I don’t believe a kinder soul ever lived. And I know this from watching her making her daily visits to the sick and being at all times ready to help somebody who was in need.”

Even the mothers of inmates sent in condolences: “She was highly appreciated by me because she was kind to the inmates, especially my son. Only two weeks ago he praised her to me. He said ‘Mother, Mrs. Lawes is right fine. Mrs. Lawes always says ‘hello boys’ in a motherly tone. And you know, she does not have to recognize us. But she does.’”

The inmates were inconsolable when they heard the news of her sudden and shocking death. Finally, against his instincts, Warden Lawes was forced to do the unthinkable – open up the prison gates and allow two hundred or so “old-timers” to march up the hill to the Warden’s house to pay their last respects at her bier. Two hundred men walked through the gates to freedom and two hundred men walked back into the prison.

That year, there was no Halloween party for local children, nor any Christmas presents for the inmates of Sing Sing ever again.

To this day, her good works are remembered by preachers and highlighted in their prayers and sermons.

[1] The Whitewright Sun (TX) 11 Dec 1947

[2] Find them in the Lewis Lawes Archive at John Jay College