Lorraine Hansberry

1930 – 1965

Playwright

Author

Civil Rights Activist

***Local Connection: Bridge Lane, Croton-on-Hudson***

Lorraine Hansberry was born in Chicago, IL to Carl August Hansberry, a successful real estate speculator (known as “The Kitchenette King of Chicago”) and Nannie Louise Perry, a teacher.

When Hansberry was 8, her parents purchased a house in a white neighborhood, but faced intimidation and threats from the residents who tried to force them to leave. Hansberry remembered rocks being thrown through their windows, and her mother prowling the house after midnight carrying a German Luger pistol when Carl Hansberry was away on business.

Illinois courts upheld the ongoing eviction proceedings and found that by purchasing their house, the Hansberrys had violated the “white-only” covenant of that subdivision. However, Hansberry’s father took the case all the way to the United States Supreme Court and won.

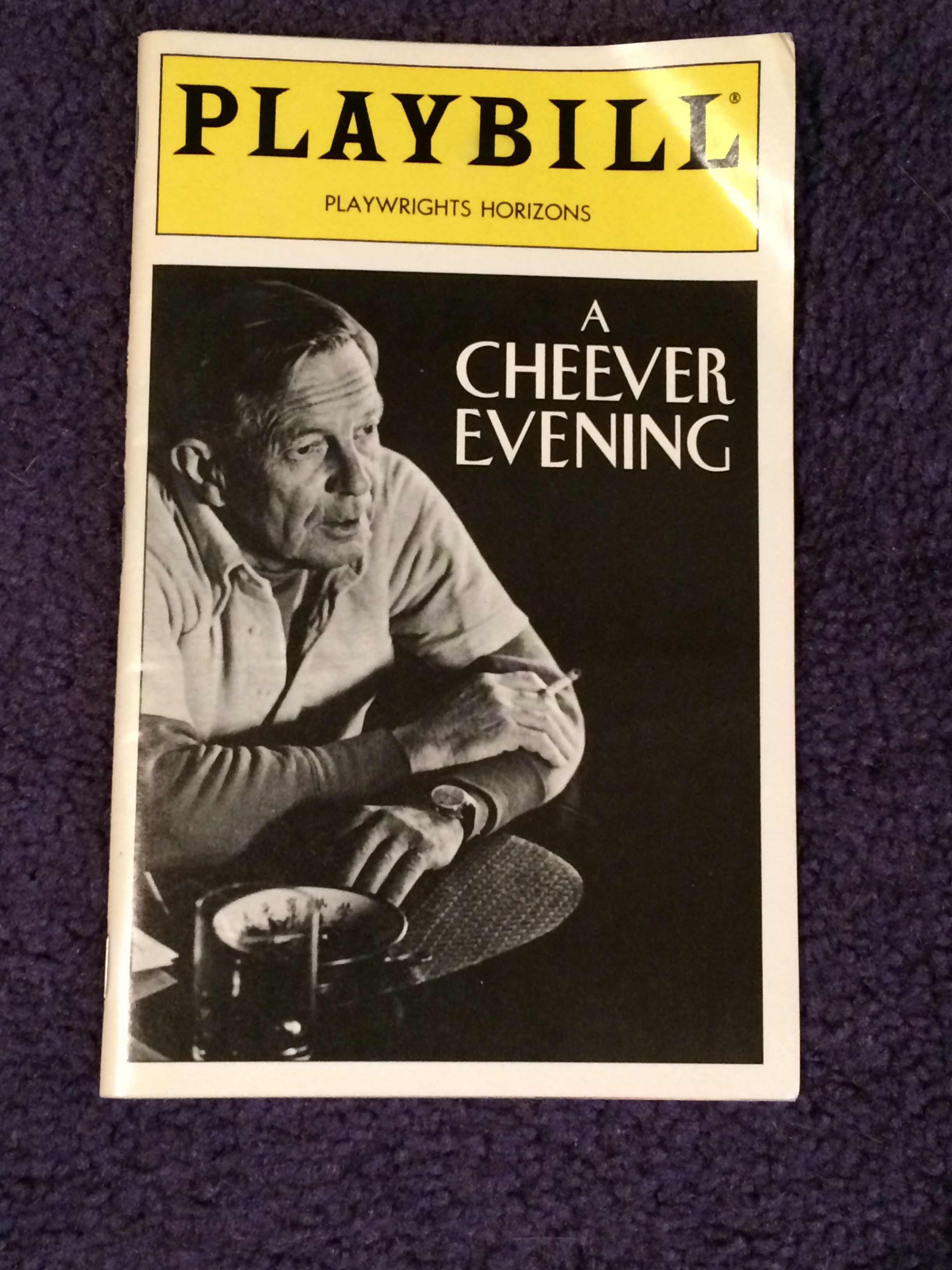

This experience would inspire Hansberry’s most famous play A Raisin in the Sun.

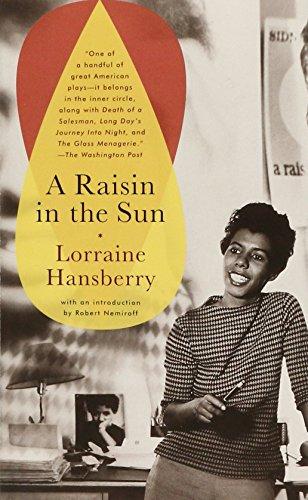

In 1950, Hansberry moved to New York City to pursue a career as a writer. Landing first in Harlem, she began working for Paul Robeson’s Black, radical newspaper Freedom, a monthly periodical.

At Freedom, she quickly rose through the ranks from subscription manager, receptionist, typist, copy editor to associate editor, along the way writing articles and editorials for the paper. It was during this time that she wrote one of her first theatrical pieces, a pageant for “The Freedom Negro History Festival” that would feature Paul Robeson, Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier, among other luminaries.

In 1953, she married Robert Nemiroff, a book editor, producer, and composer of the hit single “Cindy, oh Cindy.” They moved to 337 Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village and it was here, in 1957, that she wrote her semi-autobiographical play A Raisin in the Sun.

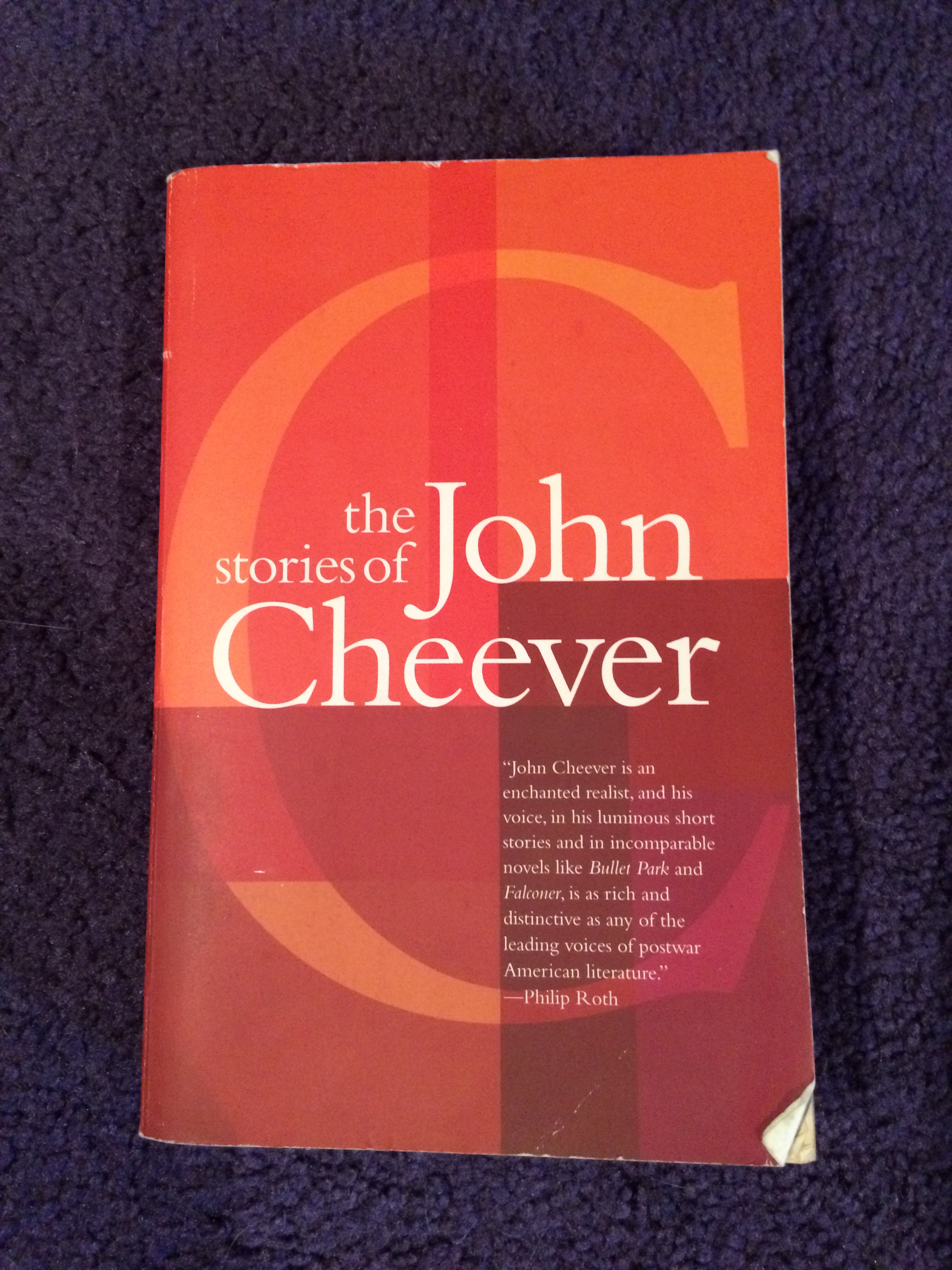

It took the producers nearly two years to raise the funds, as investors were wary of backing the first play of an unknown 26-year-old Black woman. Premiering in New Haven, Connecticut, A Raisin in the Sun opened on Broadway in March 1959 and was the first Broadway show to be written by Black woman and the first to be directed by a Black man (Lloyd Richards.) Starring Sidney Poitier, Ruby Dee and Claudia McNeil, the production was nominated for four Tony Awards. The original production ran for 530 performances – a remarkable feat in those days and would make a successful transfer to the big screen in the 1961 movie written by Hansberry and starring most of the Broadway cast. Today it is a staple of high school and college curricula and is considered one of the greatest American plays of the 20th century. It continues to be produced all over the world.

After the success of A Raisin in the Sun, Hansberry purchased a townhouse in Greenwich Village.

Soon after, she would purchase a house in Croton-on-Hudson. Ironically calling her Bridge Lane home, “Chitterling Heights,” it became her escape from the city, her writing studio, and a place where Black artists and progressives (such as Langston Hughes, Alex Haley, and Ruby Dee) would gather.

Hansberry’s Broadway success catapulted her into the whirlwind of popular intellectual discourse, and she used her newfound fame to speak out on things that mattered to her. She became a star speaker, dominating panels, podiums and television appearances. Her quick wit and provocative stances made her popular with the media as she could always be counted on for spirited discussion.

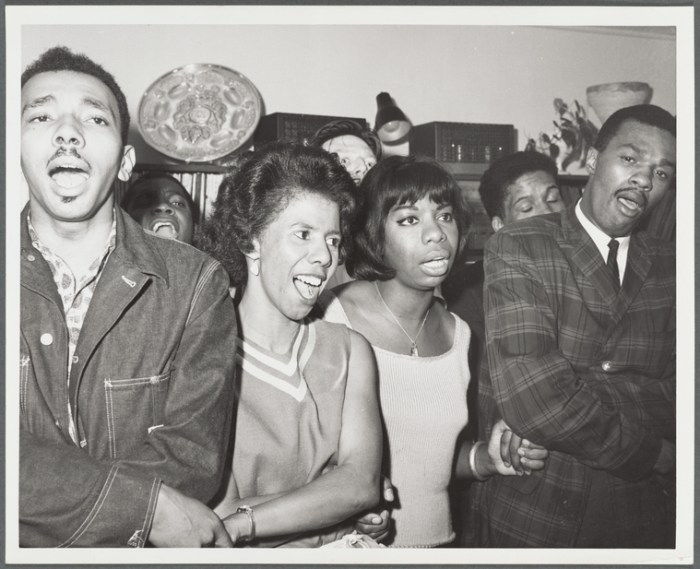

She was deeply involved in the Civil Rights movement, appearing at numerous events and meeting with political leaders:

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

By 1963, as one of the intellectual leaders of the civil rights movement, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy would meet with her, James Baldwin, Lena Horne, Harry Belafonte and others for advice on civil rights and school desegregation initiatives. (Read a May 25, 1963 New York Times article about this meeting here.)

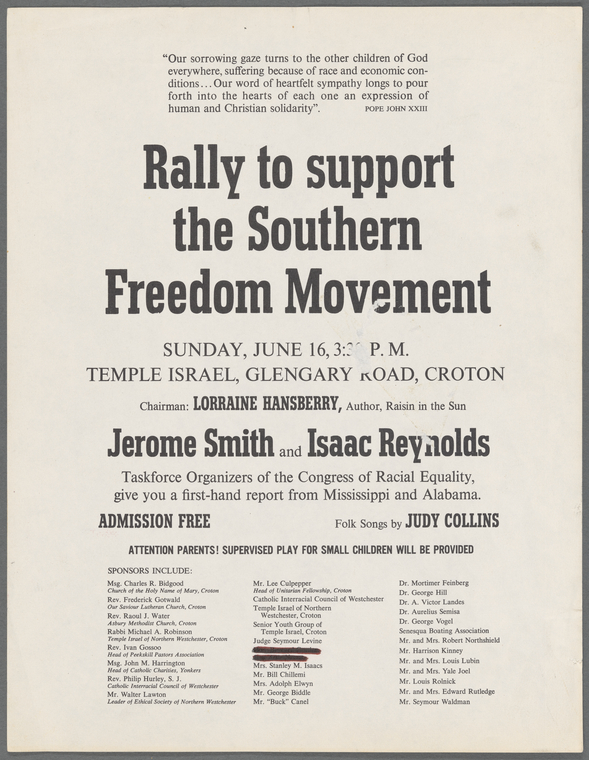

In 1964, Hansberry was integral in organizing and participating in one of the first fundraisers in the New York City area for the civil rights movement, held at Croton’s Temple Israel. (The 1963 Birmingham church bombings catalyzed many on the East Coast.)

She was the MC of the event, and brought in other like-minded celebrities, including Ossie Davis, James Baldwin, and Judy Collins. They raised over $11,000 for organizations like the Congress of Racial Equality – Freedom Summer voter registration project (CORE), the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the NAACP.

Some of the money raised went towards the purchase of a Ford station wagon that Freedom Riders James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were driving the night they were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

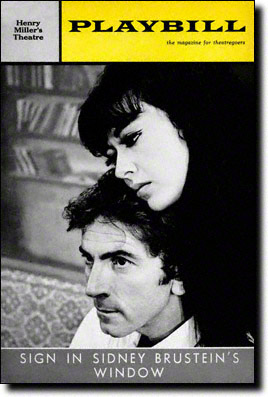

Unofficially separated for several years, Hansberry would divorce Robert Nemiroff in 1964, though they remained close collaborators and business partners to the end of her life. Nemiroff produced her final play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which opened on Broadway in October 1964.

In January 1965, Hansberry would die from pancreatic cancer at the age of 34, two days after The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window closed.

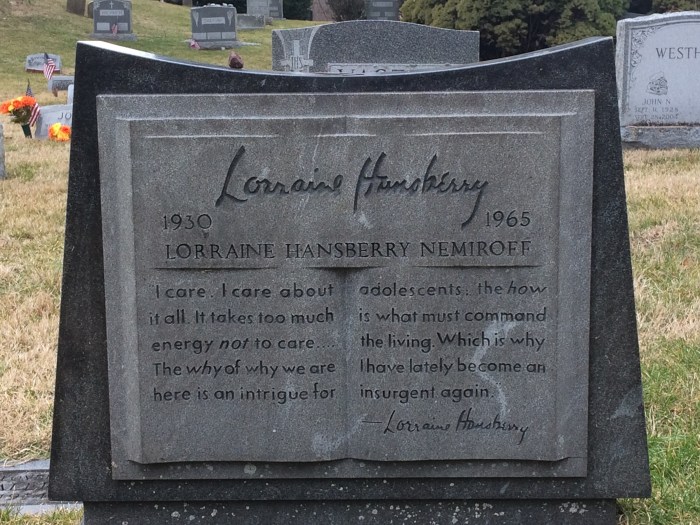

She is buried in the Bethel Cemetery in Croton-on-Hudson, New York.

CODA:

“You are young, gifted, and black. In the year 1964, I, for one can think of no more dynamic combination that a person might be.”

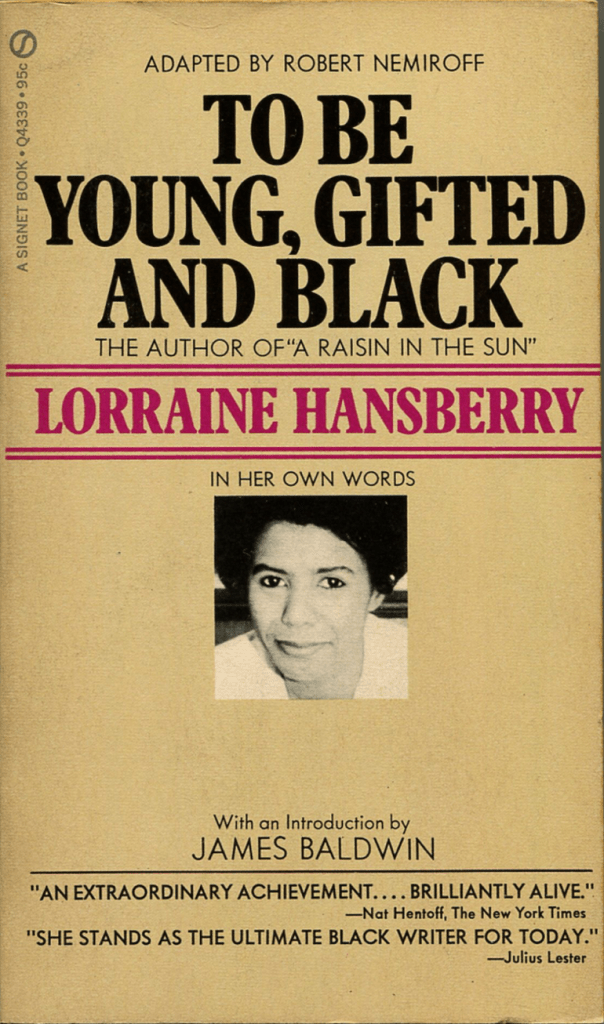

The above quotation comes from a talk Lorraine Hansberry gave to six teenage winners of a Readers’ Digest/ United Negro College Fund writing contest. In 1968, ex-husband and literary executor Robert Nemiroff would compile many of Hansberry’s unfinished and unpublished works into an off-Broadway play called Young, Gifted and Black. This in turn would be adapted into a posthumous autobiography of the same name published in 1969.

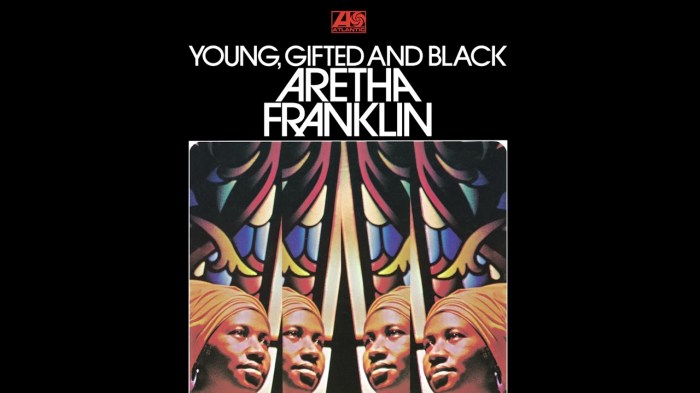

Singer/Songwriter Nina Simone would be inspired to write and record a song with that title and in 1972, singer Aretha Franklin would release an album of the same name.

There have been numerous productions of her seminal play A Raisin in the Sun – on Broadway and off-, internationally, in regional theaters, on television and film. In 1973, a musical version of the play, called Raisin won the Tony Award for Best Musical. In 2010, playwright Bruce Norris wrote Clybourne Park which tells the story before and after the events of A Raisin in the Sun and in 2013, Kwame Kwei-Armah wrote Beneatha’s Place which imagines what happened to the character of Beneatha after the events of A Raisin in the Sun.

It is a play and a story that continue to inspire.

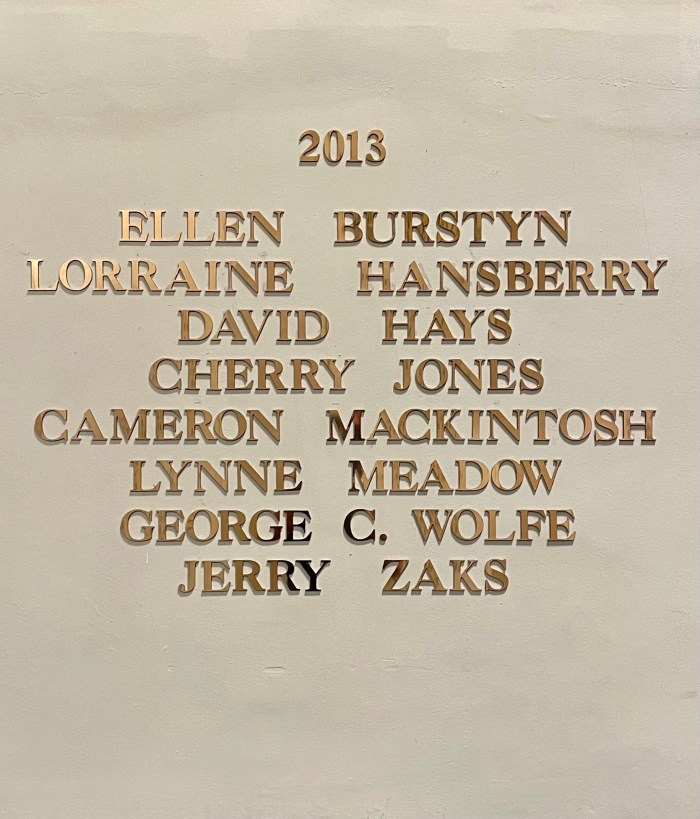

Yet, it took until 2013 for Lorraine Hansberry to be inducted into the Theatre Hall of Fame:

Finally, today, in addition to her other accomplishments, Lorraine Hansberry is now being hailed as a figurehead of the LGBTQ movement. However, this is a little tricky, as Hansberry was not out during her lifetime. For five decades after her death, ex-husband and literary executor Robert Nemiroff restricted access to any of Hansberry’s writings that explored her sexuality. It wasn’t until 2013 that researchers were allowed to see these previously hidden articles, letters, and journal entries. Since then, Hansberry has emerged as a queer icon. Her published works from this cache, often signed only with her initials, reveal a thoughtful and progressive thinker, while her private writings offer a new perspective on this multifaceted artist.

She doesn’t look too happy, does she?

She doesn’t look too happy, does she?