Come on down to the Ossining Public Library at 2pm on Saturday, February 21, 2026 and get your (signed if you want!) copy of Ossining’s newest history book.

Come on down to the Ossining Public Library at 2pm on Saturday, February 21, 2026 and get your (signed if you want!) copy of Ossining’s newest history book.

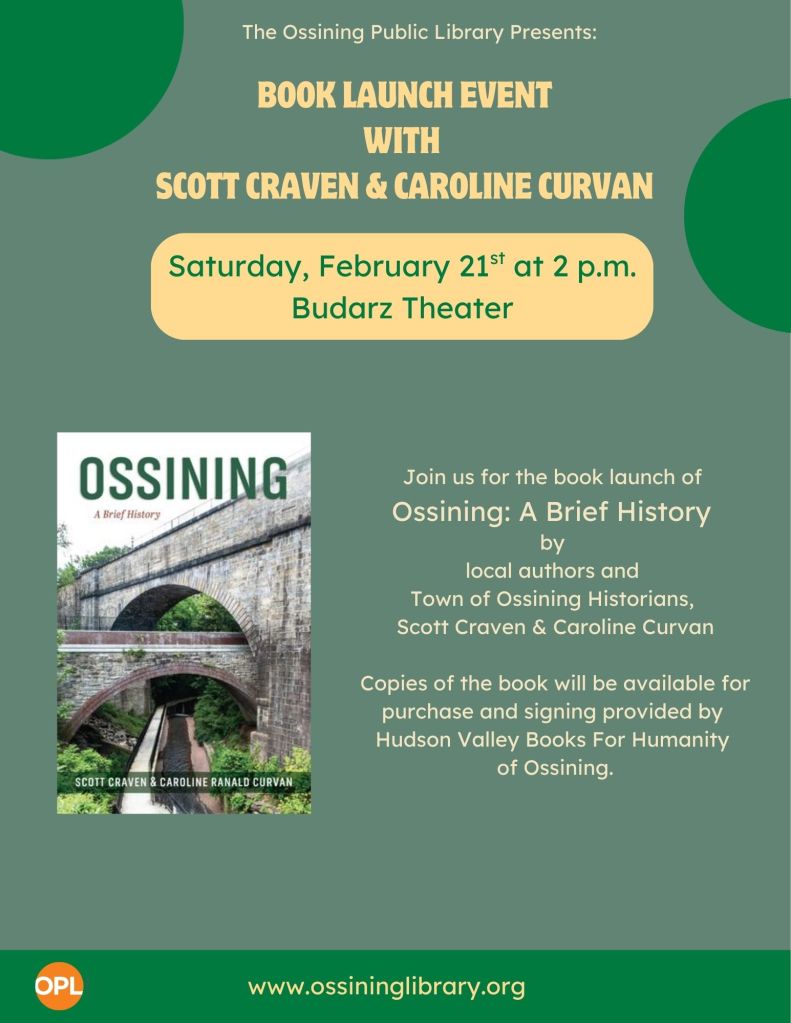

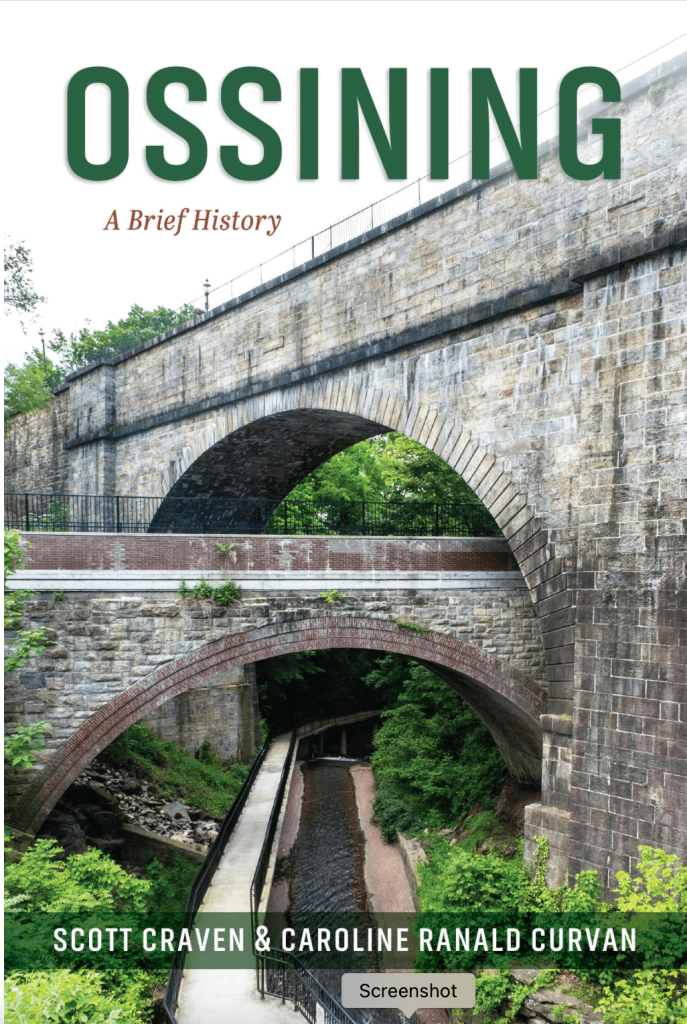

It’s almost here! Our new book, Ossining: A Brief History, will be released on February 10, 2026. Here’s a sneak peek at the cover — what do you think?

Check out the publisher’s website here to pre-order, or visit your favorite brick and mortar bookshop after its release.

We’ll be doing an official book launch at the Ossining Public Library on Saturday, February 21, 2026 at 2pm — watch this space for more info on that and other events coming your way soon!

Folks, this is just a short post to direct you to the Sing Sing Prison Museum website where you can learn more about the history of this iconic penitentiary, as well as read three posts I recently wrote for their blog about religion in Sing Sing Prison.

[Note that the Museum is on track to open very soon, and in the meantime is offering numerous events to the public as they complete construction on their space in Ossining’s historic Olive Opera House.]

2. Chaplains of Sing Sing – Mr. Gerrish Barrett, Sing Sing’s First Prison Chaplain

3. The Fight for Sing Sing’s Soul – The Tenure of Reverend John Luckey, 1839-1865

Check this out! I just happened upon the Agate Passage over which the Agate Bridge spans, connecting the Kitsap Peninsula to Bainbridge Island (north of Seattle, Washington.)

And guess who they’re named after? Ossining’s own Alfred Agate!!

How did this come to be?

Well, if you’ve been following this blog, you’ll know that I’ve been quite obsessed with artist Alfred Agate, born in the Sparta neighborhood of Ossining in 1812. He went on to be an artist/illustrator on the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1838 – 1842 (aka the USXX.)

See here and here for a refresher.

To recap briefly, the USXX was the largest U.S expedition you’ve never heard of, and its mission was multi-pronged:

It’s this last bullet point that interests us.

The expedition began with six ships, but lost one rounding Cape Horn in 1838, and sent one home in 1839, so by the time they were approaching the West Coast of North America in 1840, there were only four ships. At this point in the expedition, leader Lt. Charles Wilkes was often splitting his armada up to save time and maximize efficiency.

In December of 1840, our Alfred was aboard the USS Peacock which was trying to complete numerous complex missions, such as surveying the western edge of the South Pacific whaling grounds, correcting some previous USXX surveys of Samoa, and arresting a couple of Samoan chiefs because Lt. Wilkes said so. She and her crew were supposed to complete all this in time to meet the rest of the ships at the mouth of the Columbia River by May 1, 1841.

Lt. Wilkes had gone ahead with his other two ships, the USS Vincennes and the USS Porpoise, taking them into the Strait of San Juan de Fuca between the northern edge of Washington State and Vancouver Island on May 1, 1841. For 2 ½ months they would meander down to Puget Sound surveying as they went. (Of course, the British-held Hudson’s Bay Company was firmly ensconced there, trading in beaver and other skins, among other things. But that didn’t stop Lt. Wilkes . . . )

In late May, Lt. Wilkes would travel overland back down to the mouth of the Columbia River to meet up with the USS Peacock, but it would not be there. With no way to contact them, he had no idea where they were or what was making them so late. He left his ship’s purser, Waldron, to wait for them. After six weeks, Waldron would abandon his post, leaving his Black servant John Dean to wait in his stead. Good thing too, because Dean would make friends with the local Chinook Indians, and turn out to be a quick, decisive leader. When the Peacock finally did arrive in mid-July, she would founder on the bar at the mouth of Columbia. Our Alfred, his illustrations and the rest of the crew survived only because Dean dispatched several canoes of Chinook to save all hands before she sank in ignominy.

But back to Agate Passage – I cannot find any explanation as to WHY the surveying crew of the Vincennes/Porpoise would name this passage after Alfred (I mean, he wasn’t aboard either ship surveying this region.) However, the Agate Passage (over which the Agate bridge was built in 1950) had apparently been missed by previous explorers and so remained unnamed by Europeans. (Captain George Vancouver’s 1792 expedition, I’m looking at you!)

Of course, the native Suquamish people knew of this passage as it bordered their land, and likely had their own name for it (though I also haven’t discovered this.)

But, as we know, European explorers liked to rename everything to honor their people, so Agate Passage this became.

My theory is that because the USS Peacock was so tardy in arriving at the Columbia River, the remaining crew feared that the ship was lost. And they all seemed to admire our young illustrator, being especially moved by the way he handled a debacle in Fiji when two USXX crew members, Lt. Underwood and midshipman Wilkes Henry were murdered in retaliation for the kidnapping of a Fiji chief. (See here for that story)

So, perhaps this was why they decided to name this passage after Alfred Agate.

What do you think?

* This title is a bit of clickbait because now you know Alfred Agate wasn’t ever in Seattle — he would get to the mouth of the Columbia River and then immediately head south.

Welcome to the virtual exhibit page for Ossining Women’s History Month 2025!

While the installation at the Ossining Public Library (53 Croton Avenue) is no longer on display, the entire exhibit will live on this blog in perpetuity.

Who are these women?

These are all remarkable women local to Ossining who made a big impact in shaping our community and our world. Some are national figures. Some have local streets, schools or parks named after them. And some just did their work quietly. But all have accomplishments that deserve to be recognized and shared.

What will you see?

This is a retooling and enlargement of last year’s exhibit presented at the Bethany Arts Community, with expanded biographies and four more fascinating women included.

These women represent all facets of American life – art, religion, science, politics, military service, activism, and philanthropy. Those with a higher profile in life offer more images and material. Others avoided the limelight (either on purpose or through circumstance) and less is known about them, but this exhibit will help uncover and celebrate all of their remarkable stories.

To learn more about each woman featured, simply click on their names below and you’ll be quickly directed to a page with their detailed biography, including photos and links to further enrich their extraordinary stories.

Enjoy!

Caroline Ranald Curvan

Ossining Town Historian & Exhibit Curator

Before you go . . .

Help me curate Women’s History Month 2026!

I’d like to add to this group of Local Legends by crowd-sourcing nominations for next year’s Women’s History Month exhibit.

Who would you like to see honored and why? (They should be women who have some connection to the Ossining area . . .)

You can either fill out this brief form online or complete a hard copy at Ossining Library (downstairs in the exhibit gallery.)

Eliza Wood Farnham

1815 – 1864

Writer

Activist

Abolitionist

Prison reformer

***Local Connection: Matron of Mt. Pleasant Women’s Prison (aka Sing Sing Prison)***

In a society that portrayed the ideal woman as submissive, pure, and fragile, Eliza W. Farnham created her own concepts of female identity. Her theories and actions, occasionally contradictory, offered alternatives to women who felt confined by the limited roles prescribed by their culture. As Catherine M. Sedgwick, a contemporary writer and friend wrote of her “She has physical strength and endurance, sound sense and philanthropy . . . [and] the nerves to explore alone the seven circles of Dante’s Hell.”

Born in Rensselaerville, New York, Eliza Burhans’s early childhood was marked by the death of her mother and abandonment by her father. Growing up with harsh foster parents, she became a self-sufficient, quiet autodidact, reading anything and everything she could get her hands on.

At 15, an uncle would retrieve her from the foster home, reunite her with her siblings and arrange for her to go to school. By 21, she had married an idealistic Illinois lawyer, Thomas Jefferson Farnham, and set off with him to explore the American West.

Eliza would have three sons in four years, though only one would survive childhood. Thomas and Eliza would write up their observations of the West — he would become a popular travel writer of the day, and she would publish her memoir, Life in Prairie Land, in 1846.

In 1840, the Farnhams returned east and settled near Poughkeepsie, New York, where Eliza became deeply involved in the intellectual and reform movements of the day. An early feminist who believed that women were superior to men, Eliza wrote articles in local magazines against women’s suffrage, believing that women could have a much greater impact as mothers and decision makers in the home. (However, in their 1887 History of Woman Suffrage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony would write that Eliza’s attitudes evolved and that she ultimately saw the necessity of and supported women’s suffrage.)

Eliza also became interested in prison reform at the time, and in 1844 sought and was appointed to the position of Matron of the Mt. Pleasant Female Prison, at the time infamous for its chaos, rioting and escapes, to prove that kindness was a more effective method of governance than brutality.

She instituted daily schooling in the prison chapel and started a small library that allowed each woman to take a book to her cell to read (making sure that there were picture books available for those who couldn’t read.) She also believed that lightness and cheer were more conducive to reformation, and placed flowerpots on all windowsills, tacked maps and pictures on the walls, and installed bright lights throughout. She spearheaded the celebration of holidays, introduced music into the prison, and began a program of positive incentive over punishment. Finally, she fought to improve the food served to the women and ended the “rule of silence”, believing that “the nearer the condition of the convict, while in prison, approximates the natural and true condition in which he should live, the more perfect will be its reformatory influence over his character.” [1]

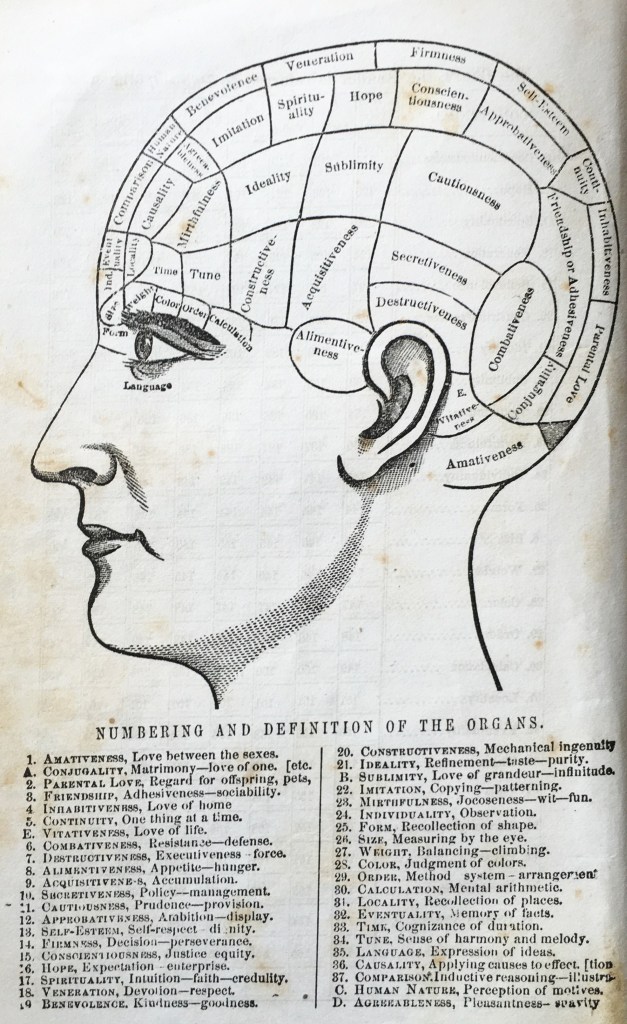

It must be said that her methods were deeply influenced by the now-discounted “science” of phrenology which looked at the correlation between skull shape and human behavior, giving a biological basis for criminal behavior (not, as many religious people believed then, sheer, incorrigible sinfulness.) Eliza would even edit and publish an American edition of a treatise by the English phrenologist Marmaduke Blake Sampson, under the title Rationale of Crime and its Appropriate Treatment. [2]

Although the mayhem that had plagued previous matrons was significantly reduced, Eliza’s approach was viewed as simply coddling the prisoners. This led to conflicts with several staff members, including Reverend John Luckey, the influential prison chaplain. By 1848, a change in the political landscape installed new prison leadership and she was forced to resign.

She would move to Boston, to work at the Perkins Institute for the Blind until her explorer-husband died unexpectedly while in San Francisco. Eliza went to California both to settle his estate and execute a plan assisting destitute women purchase homes in the West to achieve financial independence. Though that initiative was not successful, Eliza herself bought a ranch in Santa Cruz County, built her own house, and traveled on horseback unchaperoned, among other scandalous things she would detail in her 1856 book California, In-doors and Out.

In 1852, she entered into a stormy marriage with William Fitzpatrick, a volatile pioneer. During this period, she had a daughter, who died in infancy, worked on her California book, taught school, visited San Quentin prison, and gave public lectures.

Divorcing Fitzpatrick in 1856, she returned to New York and began work on what is arguably her most significant work, Woman and Her Era. In it, she would glorify women’s reproductive role as a creative power second only to that of God. She further contended that the discrimination women experienced and the double-standard of social expectations stemmed from an unconscious realization that females had been “created for a higher and more refined existence than the male.”[3]

So, her initial disdain for women’s equality and suffrage stemmed from her unique feminist philosophy that ironically saw women as superior due to their reproductive function, historically something that had always defined female inferiority. Thus, in her world view, why should women lower themselves to the level of men to achieve “equality”?

It’s a fascinating way to look at the world, no?

Eliza would give numerous lectures on this topic before returning to California and serving as the Matron of the Female Department of the Stockton Insane Asylum.

In 1862, she would work towards a Constitutional Amendment to abolish slavery and, in 1863, answer the call for volunteers to help nurse wounded soldiers at Gettysburg.

She died of consumption a year later, likely contracted during her Civil War hospital work.

She is buried in a Quaker cemetery in Milton, New York.

Major Publications:

Life in the Prairie Land (1846) A memoir of her time on the Illinois prairie between 1836 and 1840.

California, In-doors and Out (1856) – A chronicle of her experiences and observations in California.

My Early Days (1859) An autobiographical novel describing Farnham’s life as a foster child in a home where she was treated as a household drudge and denied the benefits of a formal education. The fictional heroine reflects Farnham’s own character as a tough, determined individual who works hard to achieve her goals, overcoming all obstacles.

Woman and Her Era (1864) Farnham’s “Organic, religious, esthetic, and historical” arguments for woman’s inherent superiority.

The Ideal Attained: being the story of two steadfast souls, and how they won their happiness and lost it not (1865) This novel’s heroine, Eleanora Bromfield, is an ideal, superior woman who tests and transforms the hero, Colonel Anderson, until he is a worthy mate who combines masculine strength with the nobility of womanhood and is ever ready to sacrifice himself to the needs of the feminine, maternal principle.

SOURCES

James, Edward T., et al., editors. Notable American Women, 1607-1950 : A Biographical Dictionary. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

Wilson, James Grant, et al., editors. Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography. D. Appleton & Co., 1900.

[1] NYS Senate Report, 70th Session, 1847, vol. viii, no.255, part 2, p. 62

[2]Notable American Women, 1607-1950 : A Biographical Dictionary.

[3] Farnham, Eliza W. Woman and Her Era

Anne M. Dorner

1902 – 1962

OHS 1921

Secretary to OUFSD Superintendent

Clerk of the Ossining School Board

***Local Connection: 14 Washington Avenue***

Anna M. Dorner was born on January 3, 1902, to Frederick and Ellen Dorner. Her father, born in Germany, was a prison guard at Sing Sing. By 1920, he would be promoted to the position of Assistant Principal Keeper.

Anna was the third of four siblings – William, Helen and Frederick.

She would go to Ossining High School, graduate in 1921, and by the 1925 census, she would be listed as working as a secretary. The 1930 census would give a bit more information and note that she was working as a “School stenographer.” The Ossining Public Schools Board of Education Pamphlet for 1934-35 would list her as “Anna M. Dorner, Secretary to the Superintendent, Harvey Culp.”

By 1940, she’s Anne Dorner, living in the family home at 14 Washington with her 78-year-old father, and working as a secretary to the Superintendent of the Public Schools.

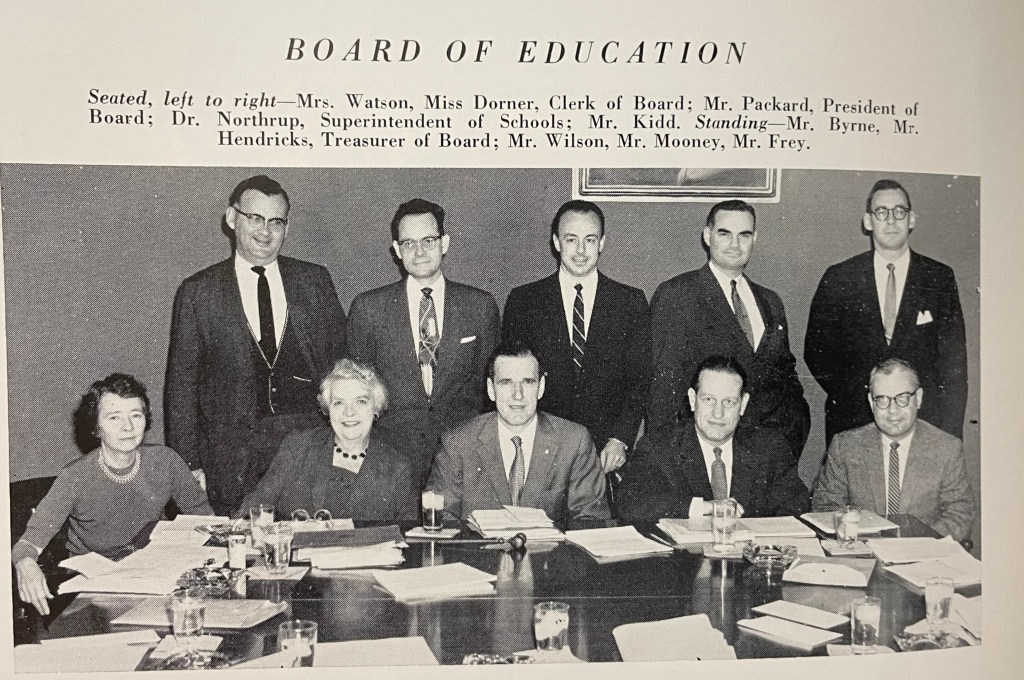

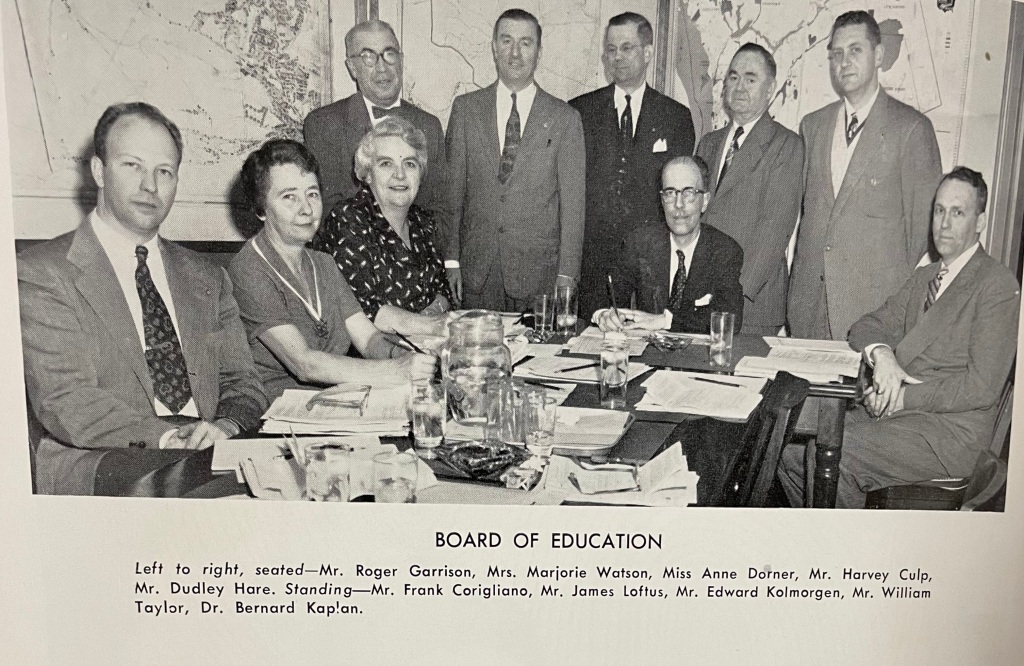

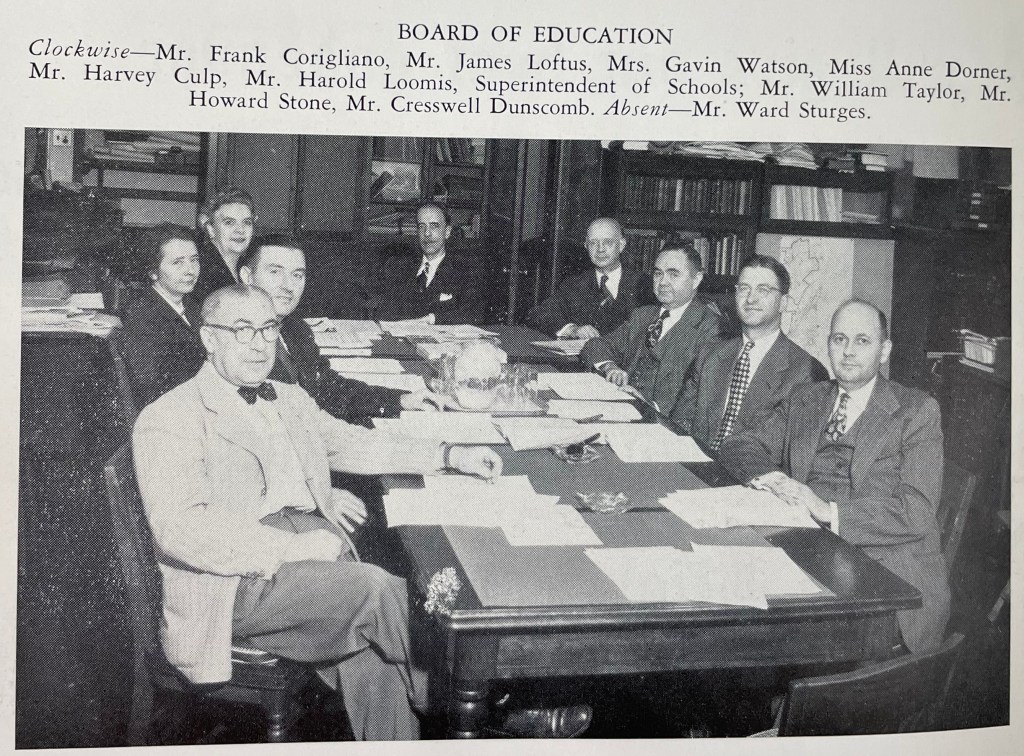

In various yearbooks, there are grainy pictures of her sitting at conference tables with school board members. She is always smiling, unlike most of the people around her:

Photos from various Ossining “Wizard” Yearbooks

Courtesy of the Ossining Historical Society and Museum

She retired in 1962 after 40 years working for the Ossining Schools, and in the yearbook that year, she received a full-page appreciation from Charles M. Northrup, the Superintendent of Schools. Among other encomiums, he writes “The world has always needed and will continue to need more individuals like you, Anne, people who put service to others above self-service. Your 40 years of dedicated work for the improvement of our schools should serve as a great inspiration to the young people of Ossining.”

She would pass away just a year later and is buried in St. Augustine’s Cemetery.

In 1966, the new Ossining middle school would be dedicated in her name.

While some may feel that she was not an august enough personage to merit such a distinction, it is a lovely gesture, to honor someone who it seems just quietly, capably and cheerfully got on with it and took care of things.

We do indeed need more people like her in the world.

Henrietta Hill Swope

1902 – 1980

Astronomer

Inventor

***Local Connection: The Croft, Teatown, Spring Valley Road***

Henrietta Hill Swope was a quiet, humble, but fiercely driven scientist whose work contributed to our current understanding of the structure of our universe.

Specifically working in the fields of Cepheid variable stars and photometry, her early work showed that that the Earth and the Sun were not at the center of the Milky Way galaxy as previously believed. From there, she surveyed all the variable stars within the Milky Way, thus tracing out the structure of that galaxy, something that had never been done before. She also helped invent LORAN, and contributed to the creation of a new technique to simply and accurately determine the distance of stars and galaxies from Earth.

Born in St. Louis, MO in 1902 to Gerard and Mary Hill Swope, Henrietta came from an extraordinary family. Her father was a financier and president of General Electric, while her uncle, Herbert Bayard Swope, was a Pulitzer-prize winning journalist, war correspondent and newspaper editor. Her mother was a Bryn Mawr graduate who would go on to study with the pioneering educator John Dewey, and later work for Jane Addams at Hull House in Chicago.

Henrietta became interested in astronomy as a young girl, and was taken to the Maria Mitchell Observatory on Nantucket where she heard lectures from Harvard’s Dr. Harlow Shapley and others.

Henrietta went off to Barnard College, where she majored in Mathematics and was graduated in 1925. (She said she chose Barnard because she “didn’t have any Latin. My father didn’t believe in any Latin. He thought I should spend that time on either sciences or modern languages.”[1])

In 1927, though she had only taken one course in astronomy, a friend alerted her to a fellowship offering for women only sponsored by Dr. Harlow Shapley at the Harvard College Observatory (HCO). She applied and was quickly accepted. (Her initial interpretation was that he was reaching out to women specifically because he “wanted some cheap workers.” Ahem.)[2]

She became Shapley’s first assistant, and while she looked for variable stars on photographic plates taken via the HCO telescope, she earned her Master’s in astronomy from Radcliffe College in 1928.

The following year, she became famous when she identified 385 new stars, accurately revealing the composition of the Milky Way galaxy. By 1934, she was in charge of all the Harvard programs on variable stars which were central to much of the astronomical research at the time.

In 1942, she left Harvard to work at MIT in a radiation laboratory, and the following year was recruited by the US Navy to work on a secret project which would come to be known as LORAN (Long Range Aid to Navigation.) This innovative technology allowed navigators to use radio signals from multiple locations to fix a precise position. She was appointed head of LORAN Division at the Navy Hydrographic Office in Washington, DC for the duration of the World War II.

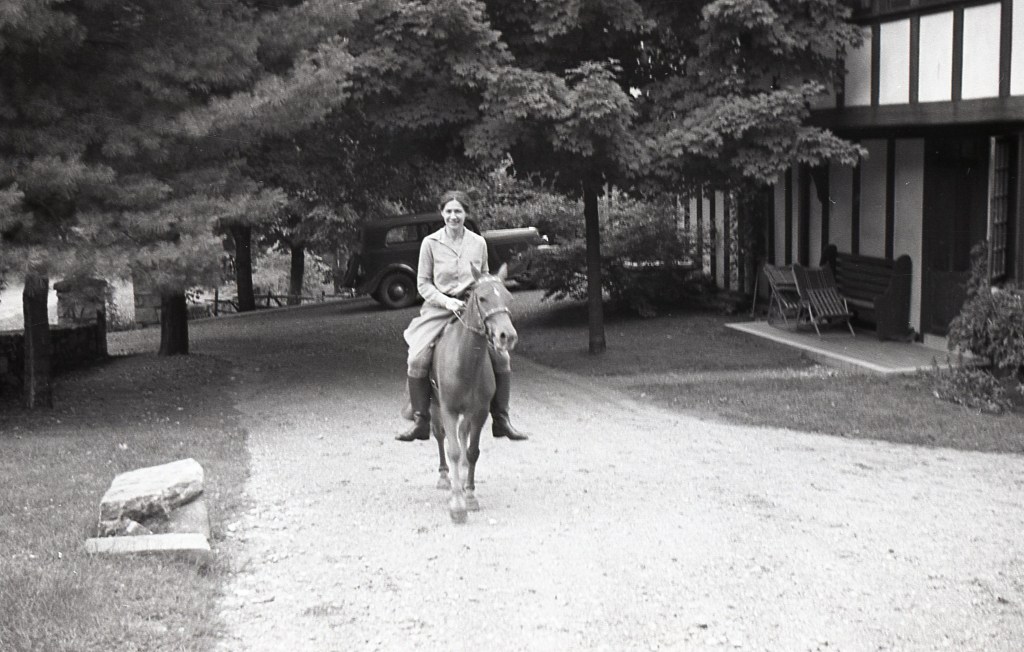

Post-WWII, she would teach astronomy at Barnard College, then relocate to California to work as a research fellow at the Mt. Wilson and Palomar Observatories, as well as teach at the California Institute of Technology (CalTech). She would visit her family’s home The Croft in Ossining a few times a year, and is remembered by a niece as being “no frills. Very sweet, otherworldly, and decidedly bluestocking, none of us knew how accomplished she was or how important her work was.”

Henrietta Swope at The Croft, c. 1930s/40s

Courtesy of Kevin Swope

During this time, Swope’s research focused on determining the brightness and blinking periods of Cepheid variable stars, and the quality and precision of her work allowed other astronomers to use these stars as “celestial yardsticks” with which to rapidly measure celestial distances. Swope herself used them to determine that the distance from earth to the Andromeda galaxy is 2.2 million light-years.

She remained at the Mt. Wilson Observatory and CalTech until her retirement in 1968.

In the 1970s, she donated funds to the Carnegie Institute of Washington to aid in the development of the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile.

The 40-inch Henrietta Swope Telescope began operation in 1971 and though Swope died in 1980, she continues to help people look to the stars.

[1] Interview with Dr. Henrietta Swope, By David DeVorkin at Hale Observatories, Santa Barbara State August 3, 1977. https://web.archive.org/web/20150112054849/http://www.aip.org/history/ohilist/4909.html

[2] IBID

Sarah “Sally” Swope

1912 – 1999

Philanthropist

Board Member

Volunteer

***Local connection: Hawkes Avenue***

Perhaps you’ve driven along Hawkes Avenue to the very outskirts of the Town and noticed this sign for the Sally Swope Sitting Park:

Who, you might then wonder, is Sally Swope? And why does she have a park named after her?

Well, she is most definitely one of those women who very quietly Got Things Done. In fact, one person interviewed commented that she was “practically allergic to being recognized for her good deeds.”

But from the 1970s until her death in 1999, Sally was a discreet force as a philanthropist and board member for, among other organizations, the Ossining Children’s Center, Westchester Community College, the Scarborough (and later Clearview) School, and Teatown Lake Reservation.

From those I’ve spoken to, she was curious, interested in people, and approachable. “Cultured”, “upper crust”, and “strong-willed” are also words that come up often in connection with her.

Sarah Porter Hunsaker was born in Brookline, Massachusetts in October 1912.

She attended the exclusive Miss Porter’s School (Miss Porter was a great-aunt of hers) and go on to study at Sarah Lawrence and Radcliffe Colleges. After college, she traveled the world and came home to work at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

In 1937, she married David Swope, a son of General Electric president Gerard Swope (and brother to the astronomer Henrietta Hill Swope.) While Sally stayed close to home in those early years as she raised her son David, Jr., and daughter Dorry, she was still active in the social sphere of Ossining.

Gradually she began extending her reach, focusing on charities that spoke to her interests – primarily children, education, and the environment. She was especially dedicated to the idea that childcare should be more than babysitting – a policy that had just been enacted at the Federal level through the Head Start programs of the 1960s. And she wanted to make sure that the Ossining’s Children’s Center was as diverse as Ossining, believing that to change society, one had to start with the youngest and most vulnerable.

She would join boards, fundraise, and be a hands-on presence. She did whatever she felt needed to be done: answering phones at the Ossining Children’s Center on occasion, serving ice pops to OCC kids who were regularly bussed across town to swim in her pool high atop Hawkes Avenue, and strategizing about the best ways to approach people for donations.

Her motto seemed to be “If you want it badly enough, you can make it happen.” And indeed, in no small part due to her contributions, the organizations with which she was involved flourished and continue to thrive decades later.

Her work extended far beyond just writing checks and attending galas – she served on boards and led committees, organizing, encouraging, and motivating her fellow volunteers. She regularly opened her house and gardens to children from the various groups in which she was involved.

And at her death, she was learning Italian. Always seeking, always learning . . .

In 2002, son David Swope, Jr., donated a parcel of land to the Town of Ossining in memory of his mother. Renovated and updated in 2024, the Sally Swope Sitting Park provides open space and meditative trails. Like its namesake, the park is a hidden gem in the midst of Ossining.

Harriet Agate Carmichael

1817 – 1871

Artist

***Local Connection: 2 Liberty Street***

One of three artistic siblings, Harriet Agate was born in Sparta in 1817. (Today Sparta is part of the Village of Ossining.)

In 1833, Harriet was one of the first women invited to show a painting at the National Academy of Design’s annual Art Exhibition. That painting was called “A View of Sleepy Hollow,” and was exhibited at the Eight Annual Exhibition, held at Clinton Hall, Beekman Street from May 14 – August 20, 1833.

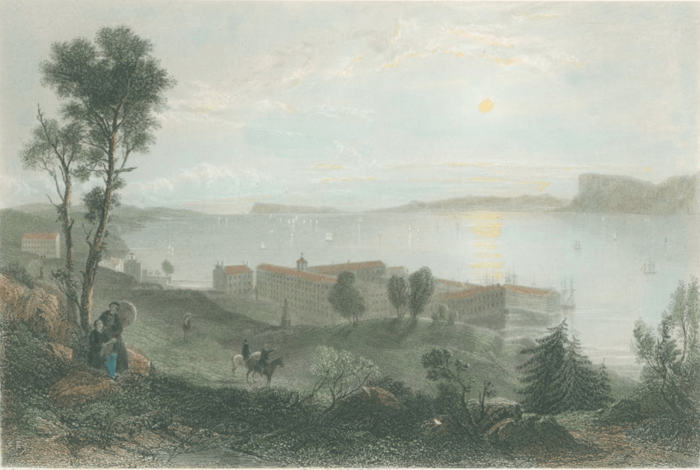

While it cannot currently be proven, I have a hunch that the painting below could be the one Harriet Agate showed at the 1833 National Academy of Design’s Art Exhibition.

Hers was titled “A View of Sleepy Hollow.”

There are only two surviving paintings known to be by Harriet:

When the Newark Art Museum accepted this painting in 1959, curator William H. Gerdts wrote the following notes:

It is an almost primitive painting, most interesting from a general cultural point of view . . . It shows a Greek soldier in costume lying on the ground with a Greek woman, also in native costume, next to him. A big Greek monument is in the centre behind him (Choragic Monument of Lysikrates I think.) Now, the subject of the picture is not known, but from the figures in it and from the time it was painted (it looks circa 1820 to 1830) I am sure it is a provincial American expression of sympathy with the Greek revolution — same time as Lord Byron’s [poem entitled “January 22, Missolonghi”] and Delacroix’s “Greek Expiring on the Ruins of Missalonghi” . . . but it is a relatively rare to see this in American art.

It is noteworthy that the people depicted in “At the Monument of Lysicrates” look particularly awkward – an indicator perhaps of the limitations placed on women artists at that time. Women would not have been allowed to take figure drawing classes, as viewing nude models would have been considered decidedly inappropriate.

This painting was included in a 1965 exhibit at the Newark Art Museum on “Women Artists of America, 1707 to 1964.”

Harriet’s two paintings and many of her brothers’ (Frederick and Alfred Agate) had been carefully kept in the attics of Agate family descendants (first in the Liberty Street house and then in another on Agate Avenue) until 1959 when Harriet’s great granddaughter, Melodia Carmichael Wood Ferguson, would discover them and give them to the Ossining Historical Society. Most were then donated to the New-York Historical Society and the Newark Art Museum, where they are not on public view but are safely stored in climate-controlled warehouses.

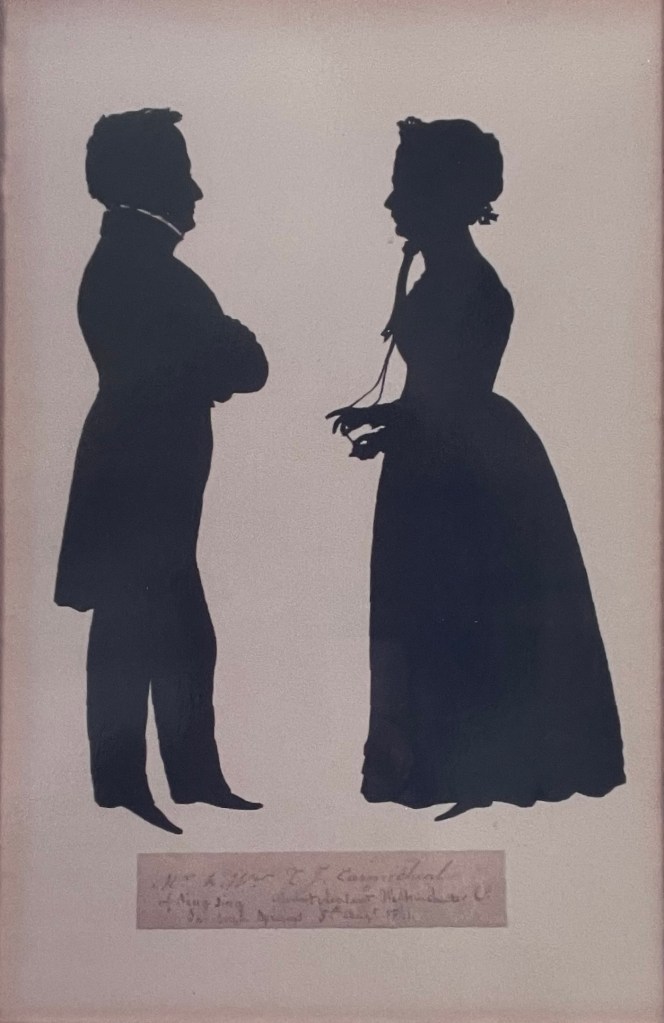

Around 1837, Harriet married Thomas J. Carmichael, a contractor for the Sing Sing portion of the Croton Aqueduct. They lived with her mother in the Agate family house at 2 Liberty Street. Harriet’s husband may have also contracted with Sing Sing Prison, then called Mount Pleasant State Prison, to use inmate labor for his stone cutting business.

Unfortunately, as was proper for women of the time, Harriet mostly seems to have lived in the shadows of the men in her life. All we have are these two paintings, the possible portrait painted by her brother Frederick, some deeds of property sales, and a few mentions of her in the biographies of her artist brothers. We don’t know if she continued painting, or if the responsibilities of motherhood and the pressure of societal norms caused her to abandon the pursuit of her art altogether.

We do, however, have this delightful silhouette of the couple:

Harriet would have five children and move to Wisconsin with her family in 1846 to live on a farm in Lake Mills. Sadly, husband Thomas died there in 1848, and after settling his estate, Harriet returned to Sparta where she lived with her mother Hannah at 2 Liberty Street and then with her daughter Melodia Frederica Carmichael Foster in Brooklyn.

Harriet died in 1871 in Brooklyn and is buried in Sparta cemetery.