Come on down to the Ossining Public Library at 2pm on Saturday, February 21, 2026 and get your (signed if you want!) copy of Ossining’s newest history book.

Come on down to the Ossining Public Library at 2pm on Saturday, February 21, 2026 and get your (signed if you want!) copy of Ossining’s newest history book.

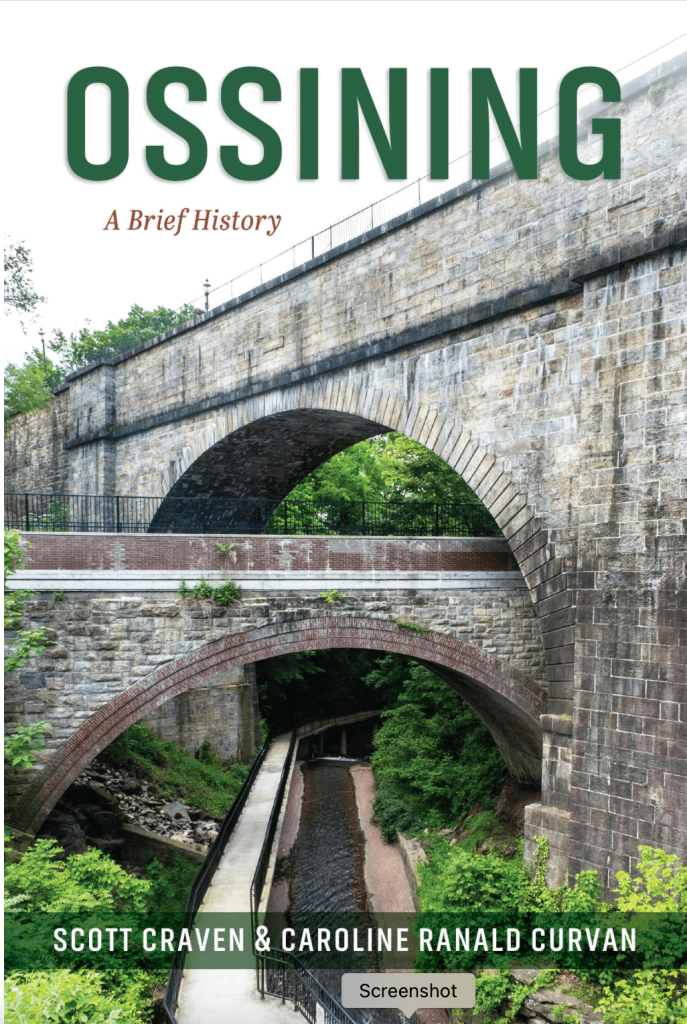

It’s almost here! Our new book, Ossining: A Brief History, will be released on February 10, 2026. Here’s a sneak peek at the cover — what do you think?

Check out the publisher’s website here to pre-order, or visit your favorite brick and mortar bookshop after its release.

We’ll be doing an official book launch at the Ossining Public Library on Saturday, February 21, 2026 at 2pm — watch this space for more info on that and other events coming your way soon!

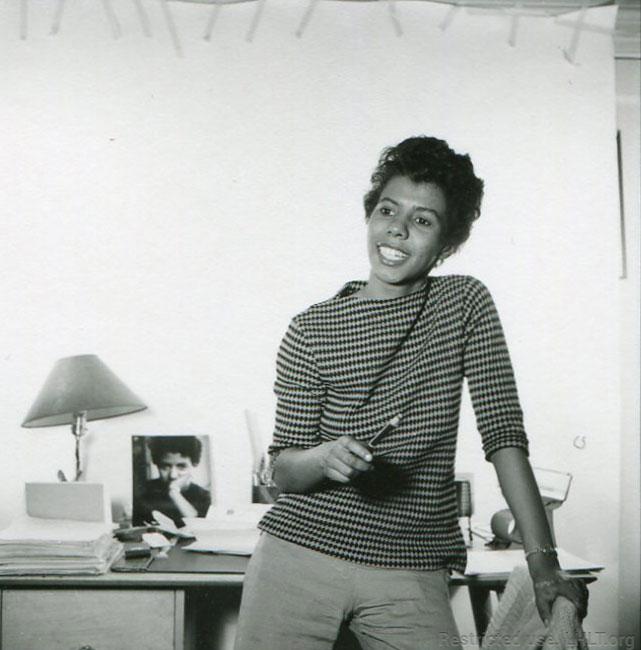

Welcome to the virtual exhibit page for Ossining Women’s History Month 2025!

While the installation at the Ossining Public Library (53 Croton Avenue) is no longer on display, the entire exhibit will live on this blog in perpetuity.

Who are these women?

These are all remarkable women local to Ossining who made a big impact in shaping our community and our world. Some are national figures. Some have local streets, schools or parks named after them. And some just did their work quietly. But all have accomplishments that deserve to be recognized and shared.

What will you see?

This is a retooling and enlargement of last year’s exhibit presented at the Bethany Arts Community, with expanded biographies and four more fascinating women included.

These women represent all facets of American life – art, religion, science, politics, military service, activism, and philanthropy. Those with a higher profile in life offer more images and material. Others avoided the limelight (either on purpose or through circumstance) and less is known about them, but this exhibit will help uncover and celebrate all of their remarkable stories.

To learn more about each woman featured, simply click on their names below and you’ll be quickly directed to a page with their detailed biography, including photos and links to further enrich their extraordinary stories.

Enjoy!

Caroline Ranald Curvan

Ossining Town Historian & Exhibit Curator

Before you go . . .

Help me curate Women’s History Month 2026!

I’d like to add to this group of Local Legends by crowd-sourcing nominations for next year’s Women’s History Month exhibit.

Who would you like to see honored and why? (They should be women who have some connection to the Ossining area . . .)

You can either fill out this brief form online or complete a hard copy at Ossining Library (downstairs in the exhibit gallery.)

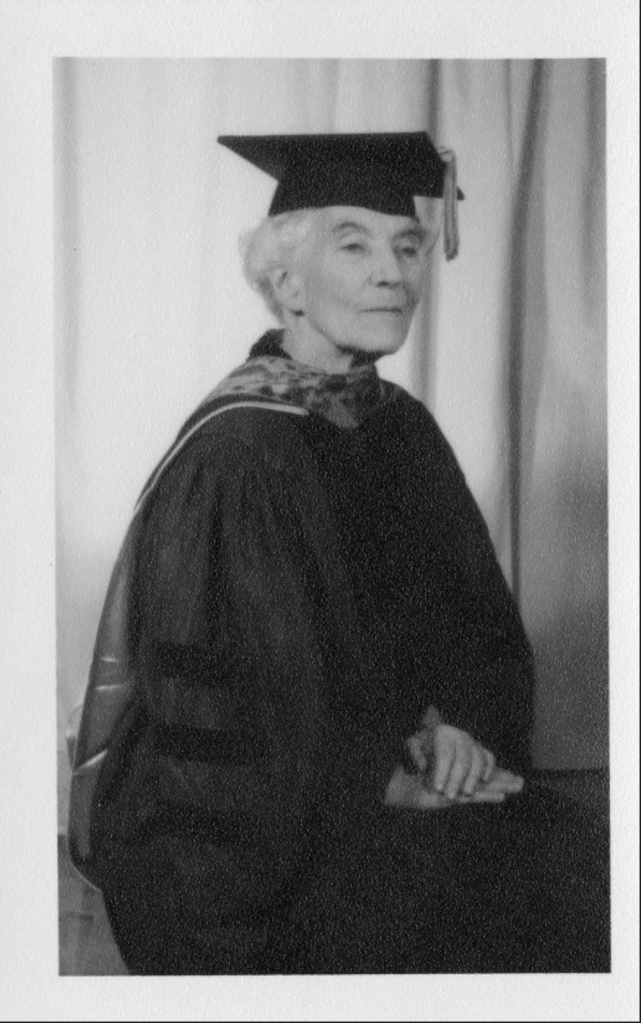

Anne M. Dorner

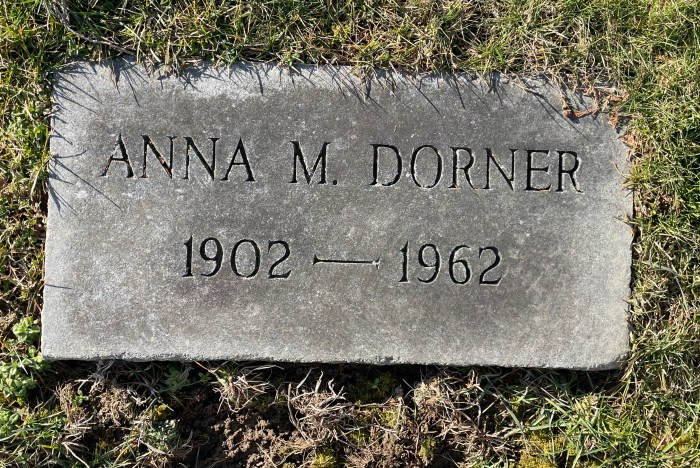

1902 – 1962

OHS 1921

Secretary to OUFSD Superintendent

Clerk of the Ossining School Board

***Local Connection: 14 Washington Avenue***

Anna M. Dorner was born on January 3, 1902, to Frederick and Ellen Dorner. Her father, born in Germany, was a prison guard at Sing Sing. By 1920, he would be promoted to the position of Assistant Principal Keeper.

Anna was the third of four siblings – William, Helen and Frederick.

She would go to Ossining High School, graduate in 1921, and by the 1925 census, she would be listed as working as a secretary. The 1930 census would give a bit more information and note that she was working as a “School stenographer.” The Ossining Public Schools Board of Education Pamphlet for 1934-35 would list her as “Anna M. Dorner, Secretary to the Superintendent, Harvey Culp.”

By 1940, she’s Anne Dorner, living in the family home at 14 Washington with her 78-year-old father, and working as a secretary to the Superintendent of the Public Schools.

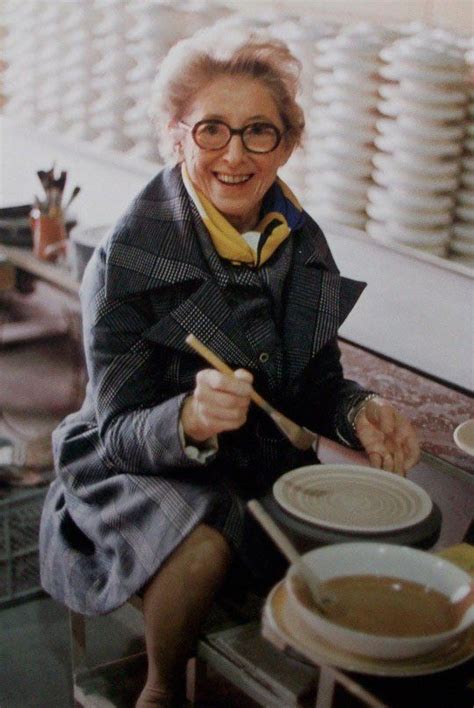

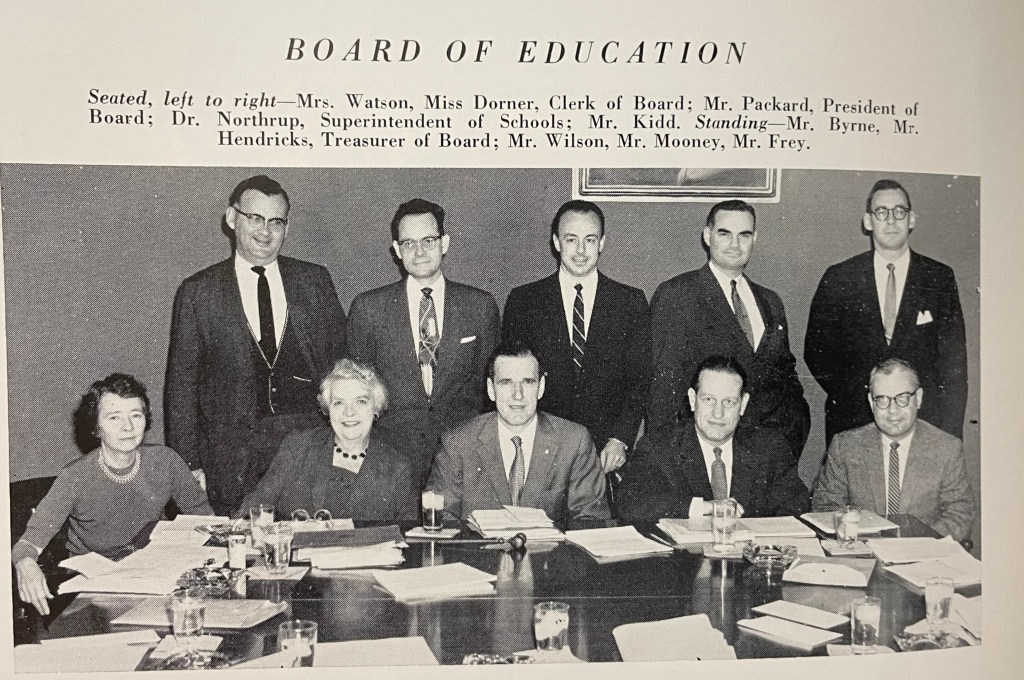

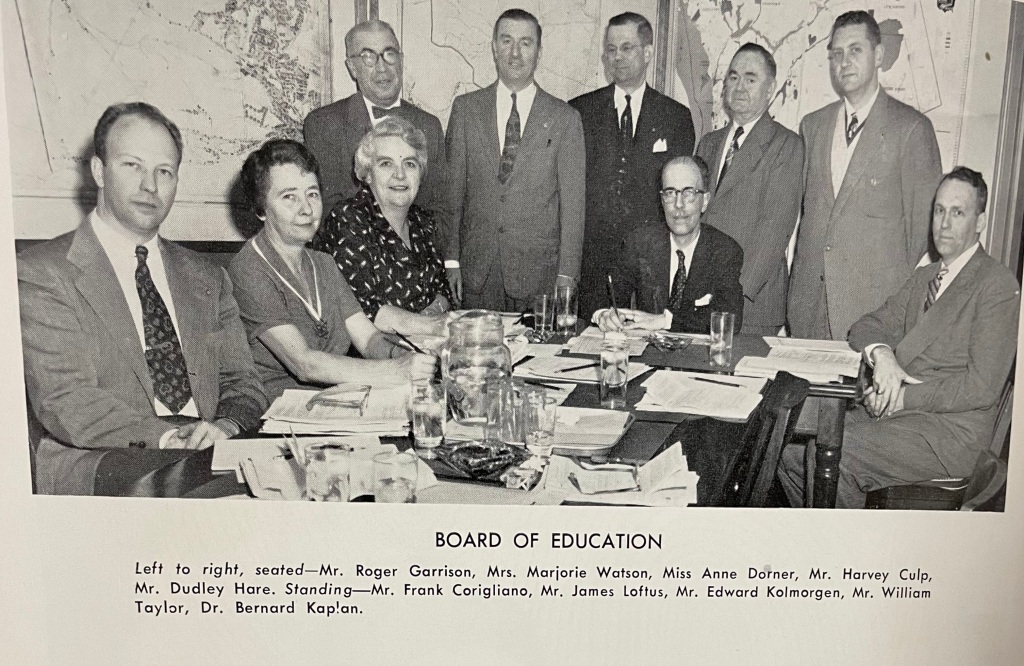

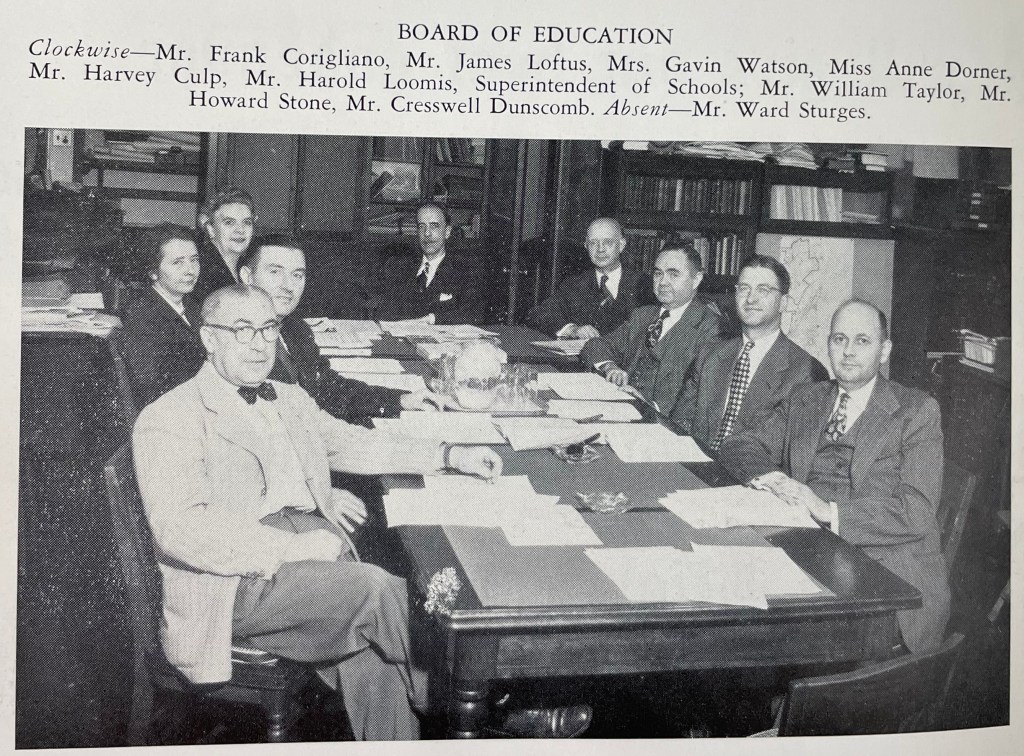

In various yearbooks, there are grainy pictures of her sitting at conference tables with school board members. She is always smiling, unlike most of the people around her:

Photos from various Ossining “Wizard” Yearbooks

Courtesy of the Ossining Historical Society and Museum

She retired in 1962 after 40 years working for the Ossining Schools, and in the yearbook that year, she received a full-page appreciation from Charles M. Northrup, the Superintendent of Schools. Among other encomiums, he writes “The world has always needed and will continue to need more individuals like you, Anne, people who put service to others above self-service. Your 40 years of dedicated work for the improvement of our schools should serve as a great inspiration to the young people of Ossining.”

She would pass away just a year later and is buried in St. Augustine’s Cemetery.

In 1966, the new Ossining middle school would be dedicated in her name.

While some may feel that she was not an august enough personage to merit such a distinction, it is a lovely gesture, to honor someone who it seems just quietly, capably and cheerfully got on with it and took care of things.

We do indeed need more people like her in the world.

Harriet Agate Carmichael

1817 – 1871

Artist

***Local Connection: 2 Liberty Street***

One of three artistic siblings, Harriet Agate was born in Sparta in 1817. (Today Sparta is part of the Village of Ossining.)

In 1833, Harriet was one of the first women invited to show a painting at the National Academy of Design’s annual Art Exhibition. That painting was called “A View of Sleepy Hollow,” and was exhibited at the Eight Annual Exhibition, held at Clinton Hall, Beekman Street from May 14 – August 20, 1833.

While it cannot currently be proven, I have a hunch that the painting below could be the one Harriet Agate showed at the 1833 National Academy of Design’s Art Exhibition.

Hers was titled “A View of Sleepy Hollow.”

There are only two surviving paintings known to be by Harriet:

When the Newark Art Museum accepted this painting in 1959, curator William H. Gerdts wrote the following notes:

It is an almost primitive painting, most interesting from a general cultural point of view . . . It shows a Greek soldier in costume lying on the ground with a Greek woman, also in native costume, next to him. A big Greek monument is in the centre behind him (Choragic Monument of Lysikrates I think.) Now, the subject of the picture is not known, but from the figures in it and from the time it was painted (it looks circa 1820 to 1830) I am sure it is a provincial American expression of sympathy with the Greek revolution — same time as Lord Byron’s [poem entitled “January 22, Missolonghi”] and Delacroix’s “Greek Expiring on the Ruins of Missalonghi” . . . but it is a relatively rare to see this in American art.

It is noteworthy that the people depicted in “At the Monument of Lysicrates” look particularly awkward – an indicator perhaps of the limitations placed on women artists at that time. Women would not have been allowed to take figure drawing classes, as viewing nude models would have been considered decidedly inappropriate.

This painting was included in a 1965 exhibit at the Newark Art Museum on “Women Artists of America, 1707 to 1964.”

Harriet’s two paintings and many of her brothers’ (Frederick and Alfred Agate) had been carefully kept in the attics of Agate family descendants (first in the Liberty Street house and then in another on Agate Avenue) until 1959 when Harriet’s great granddaughter, Melodia Carmichael Wood Ferguson, would discover them and give them to the Ossining Historical Society. Most were then donated to the New-York Historical Society and the Newark Art Museum, where they are not on public view but are safely stored in climate-controlled warehouses.

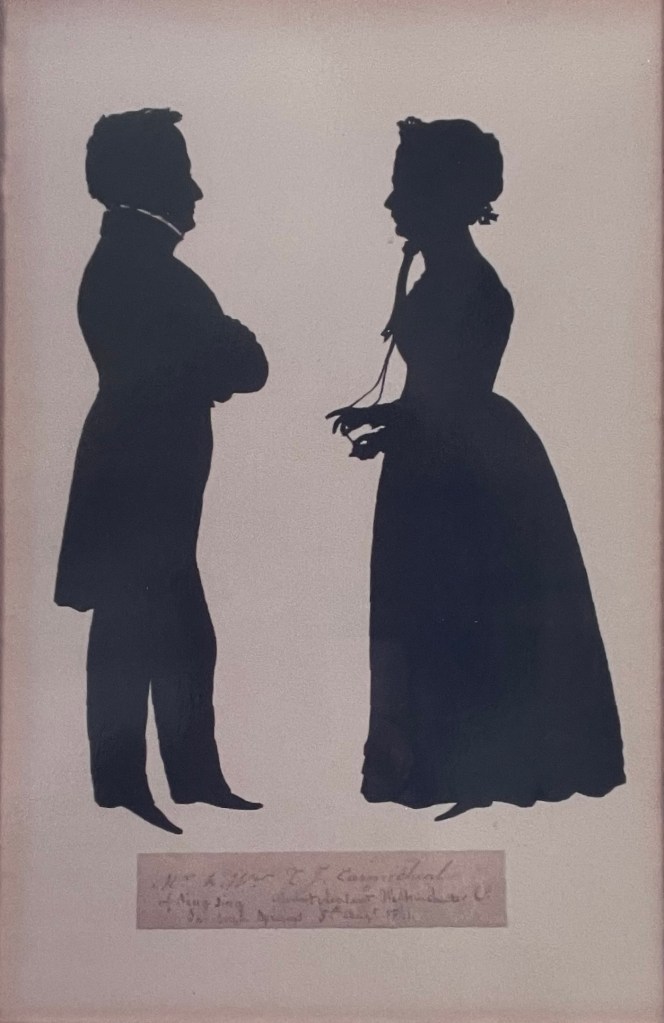

Around 1837, Harriet married Thomas J. Carmichael, a contractor for the Sing Sing portion of the Croton Aqueduct. They lived with her mother in the Agate family house at 2 Liberty Street. Harriet’s husband may have also contracted with Sing Sing Prison, then called Mount Pleasant State Prison, to use inmate labor for his stone cutting business.

Unfortunately, as was proper for women of the time, Harriet mostly seems to have lived in the shadows of the men in her life. All we have are these two paintings, the possible portrait painted by her brother Frederick, some deeds of property sales, and a few mentions of her in the biographies of her artist brothers. We don’t know if she continued painting, or if the responsibilities of motherhood and the pressure of societal norms caused her to abandon the pursuit of her art altogether.

We do, however, have this delightful silhouette of the couple:

Harriet would have five children and move to Wisconsin with her family in 1846 to live on a farm in Lake Mills. Sadly, husband Thomas died there in 1848, and after settling his estate, Harriet returned to Sparta where she lived with her mother Hannah at 2 Liberty Street and then with her daughter Melodia Frederica Carmichael Foster in Brooklyn.

Harriet died in 1871 in Brooklyn and is buried in Sparta cemetery.

Kathryn Stanley Lawes

1885-1937

“The Mother of Sing Sing”

***Local Connection: The Warden’s House, Spring Street***

(Today, the clubhouse of the Hudson Point Condominiums)

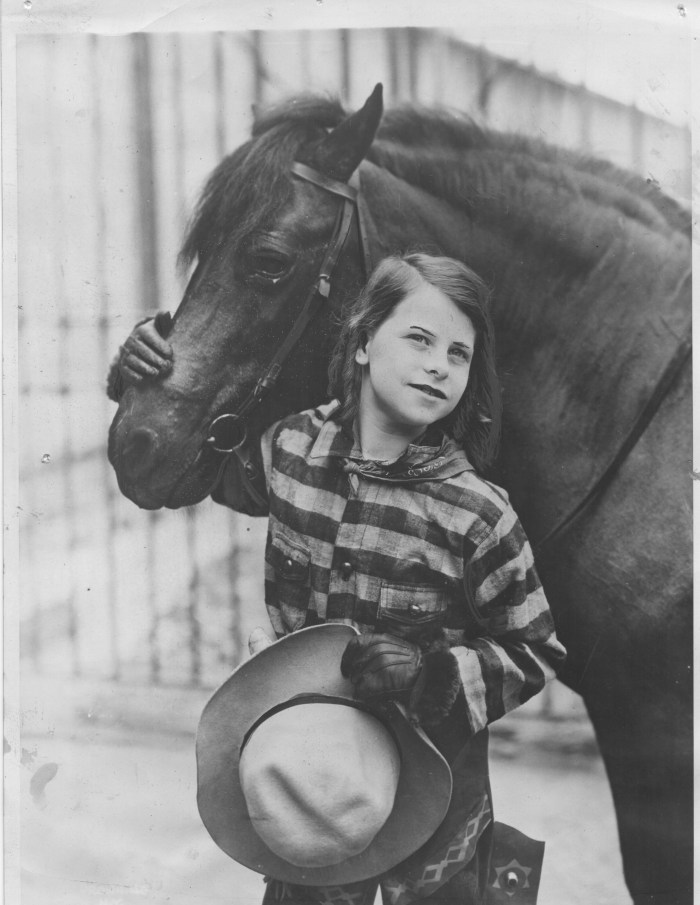

Kathryn Stanley Lawes (1885 – 1937) was known as the “Mother of Sing Sing.”

Wife of Warden Lewis Lawes, the longest tenured Prison Warden in Sing Sing’s history, she arrived at Sing Sing on January 1, 1920 with her two young daughters in tow. Settling into the drafty old Warden’s house situated next to the main cellblock, she would raise her girls (and have a third) within the walls of the prison.

She would regularly go into the prison and visit with the incarcerated. And her quiet kindnesses were the stuff of legend. She would arrange for every man to get a Christmas present – noting that some had never received one in their brutal lives. She would help them write letters to their families. Her youngest daughter, Cherie, recalled how her mother once gave away a favorite dress of hers so that the daughter of one of “the boys” could wear it to attend a high school dance.

Kathryn hosted Labor Day picnics for inmates, Halloween parties for the neighborhood children, and oversaw special meals in the mess for Thanksgiving and other holidays.

Those incarnated in Sing Sing knew that they could trust her, with one quoted as saying that telling her something was “like burying it at sea.”

In 1937, the Logansport-Pharos-Tribune wrote one of the very few articles about her, saying “When a convict’s mother or near relative was dying, the convict was permitted to leave the Sing Sing walls for a final visit. On such occasions, instead of going under heavy guard, he was taken in Mrs. Lawes’ own car, often accompanied by the Warden’s wife herself.”

She was especially solicitous to those awaiting execution, doing little things to make their cells brighter, spending hours talking to them – sometimes she would even arrange for their families to stay in the Warden’s house as the execution date drew near. She also made sure that every incarcerated man (and women) had a decent burial if they had no immediate family.

Little things, perhaps, but important.

Born in 1885 in Elmira, New York, Kathryn Stanley was ambitious and smart. At 17, she took a business course and landed a job as a secretary in a paper company. It’s around that time she met Lewis Lawes, who was working as an errand boy in a neighboring office.

But Lewis’ father was a “prison guard” (today the term is “Corrections Officer”) at the Elmira Prison, so it was rather natural that his son would eventually follow in his footsteps.

Kathryn and Lewis married in 1905 and started their family. Lewis quickly rose through the ranks in the New York prison system first in Elmira, then in Auburn. In 1915, he became Chief Overseer at the Hart Island reformatory, living right in the middle of the facility with Kathryn and their two infant daughters. Even then, Kathryn found time work with the boys in the reformatory, some who were as young as 10, giving many of them the first maternal attention they’d ever experienced.

Kathryn would be an essential participant in her husband’s success, helping cement his reputation as a progressive and compassionate Warden.

Still, it’s quite hard to flesh out Kathryn’s story. She gave very few interviews and those that she did give read like someone wrote them without ever talking to her. In fact, much of what we know about surfaced only after her mysterious death.

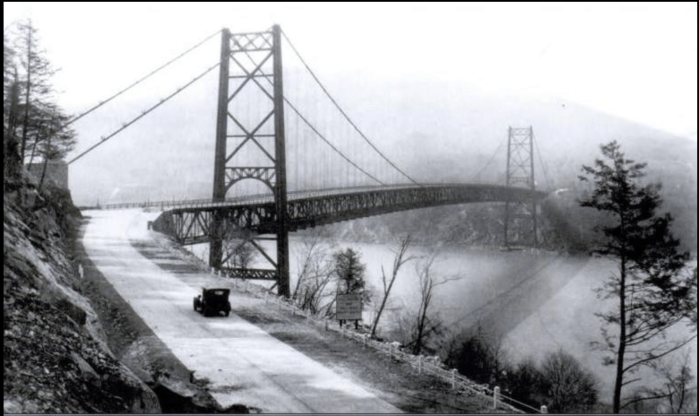

You see, one of the things that makes her story so complex and compelling is that she died at the age of 52 after falling off (or was it near?) the Bear Mountain Bridge.

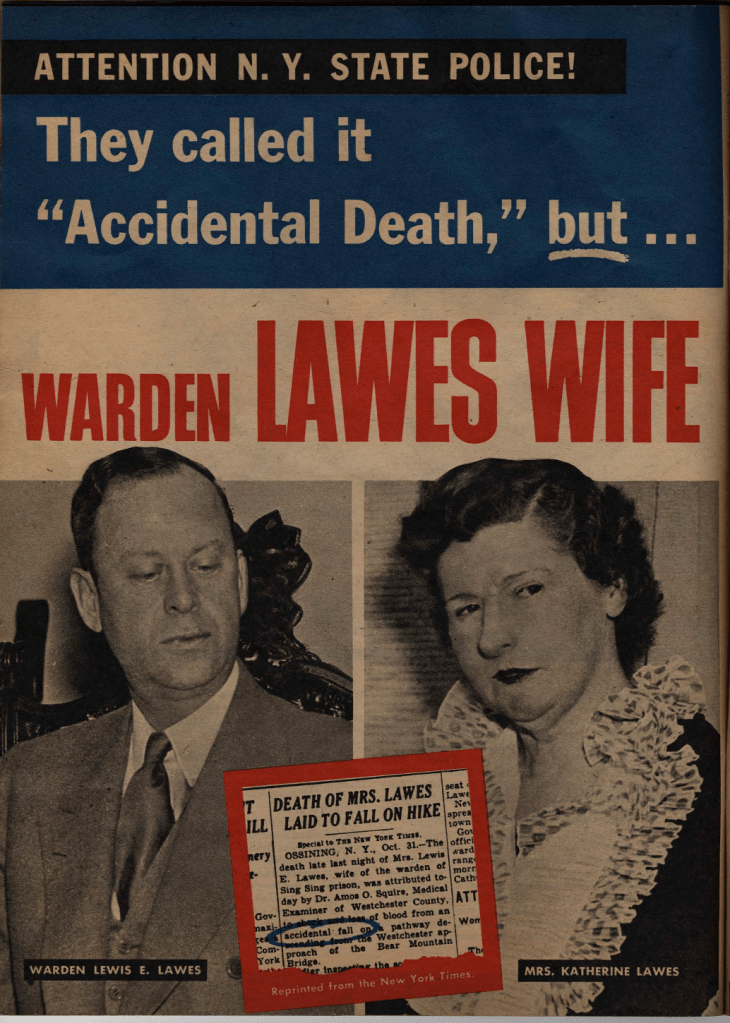

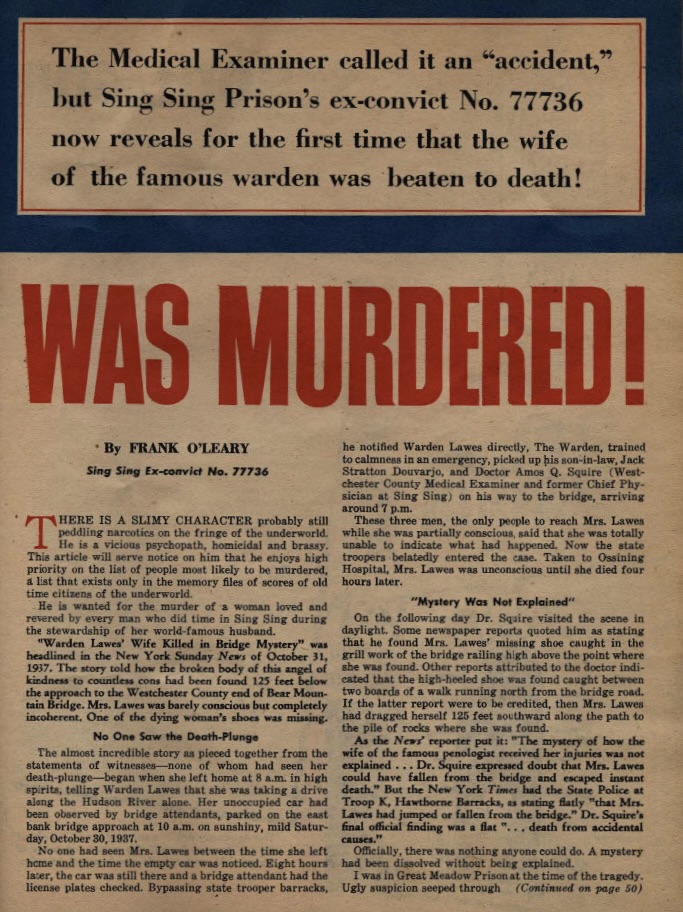

A Mysterious Death

On October 30, 1937, the New York Times published an article entitled “Wife of Warden Lawes Dies After a Fall. Lies Injured all Day at Bear Mountain Span.” In it, the New York State Police stated that she had “jumped or fallen” from the bridge. Though conscious when discovered by Warden Lawes, their son-in-law, and Dr. Amos Squire, she died in Ossining Hospital soon after from her injuries.

A few days later, a follow-up story was published in the Times that quoted heavily from Dr. Squire (the former Sing Sing Prison Doctor as well as Westchester County Medical Examiner). Dr. Squire had apparently gone back to investigate the scene of the accident. There, according to the article, he found “her high-heeled shoes caught between two boards of a walk” and concluded that she had gone hiking, perhaps venturing down the trail to pick wildflowers. He continued, “After falling and breaking her right leg, Mrs. Lawes evidently dragged herself about 125 feet southward along the path to the pile of rock where she was found exhausted.”

The men of Sing Sing were devastated when they heard the news of her sudden and shocking death. Eventually, in response to their entreaties, the prison gates were opened and two hundred or so “old-timers” were permitted to march up the hill to the Warden’s house to pay their last respects at her bier.

(In 1938, the New York Times noted that the “Prisoners of Sing Sing Honor Late Mrs. Lawes” with the installation of brass memorial tablet, paid for by the Mutual Welfare League, a organization of incarcerated individuals.)

Kathryn’s Influence

Fifteen years after her tragic death, Kathryn Lawes’ story continued to capture the attention of the press.

From a March 1953 feature in The Reader’s Digest “The Most Unforgettable Character I’ve Ever Met”, to the July 1956 exposé in tawdry Confidential Magazine below, Kathryn’s life (and death) remained compelling.

Even today, one can find sermons online that praise Kathryn Lawes’ generosity and compassion for those that society would rather forget.

Carrie Chapman Catt

1859 – 1947

Suffragist Leader

President, National American Women’s Suffrage Association

President, International Women’s Suffrage Association

Founder, National League of Women Voters

Founder, National Committee on the Cause and Cure of War

****Local Connection: Juniper Ledge, North State Road****

Carrie Chapman Catt (née Lane) was born in Ripon, Wisconsin in 1859. Unusually for that time and place, she went to college (Iowa State Agricultural College) and earned her Bachelor of Science degree in 1880. She became a teacher, a principal, then Superintendent of her Iowa school district.

In 1880, she married husband #1, Leo Chapman, editor of the Mason City Republican, who held extremely progressive ideas for the time, but died of typhoid fever within a couple of years. In 1885, she married husband #2, George Catt, a wealthy engineer and fellow Iowa State alum. He apparently was quite supportive of her involvement in the fight for women’s rights.

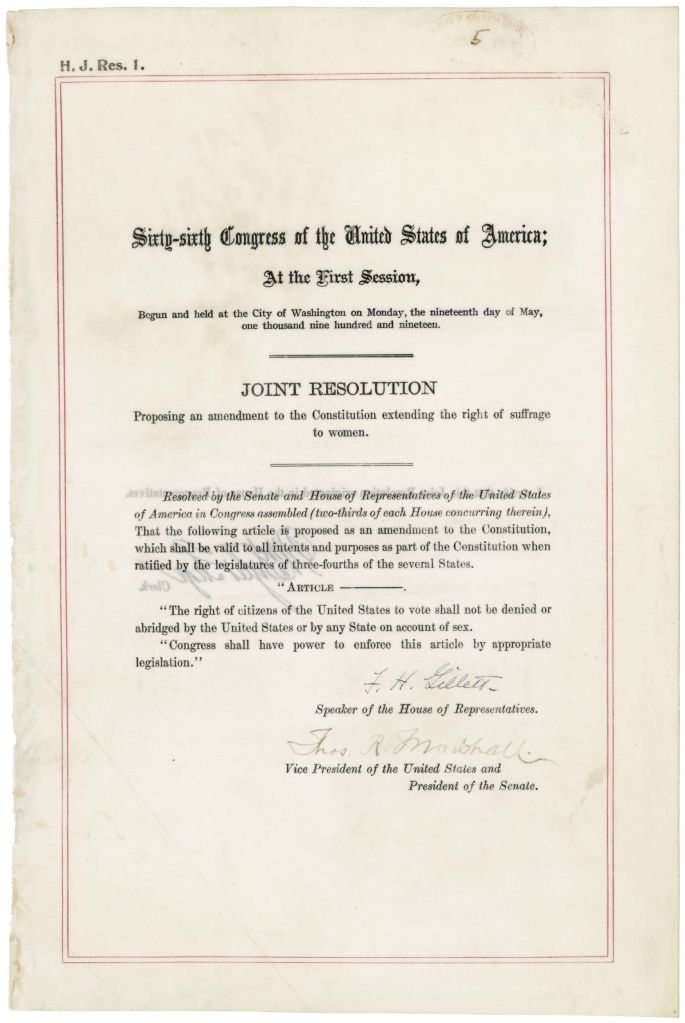

The Constitutional Amendment to give women the right to vote was first proposed in 1878. Catt became involved with the fight soon after. By 1890, she was president of the Iowa Women’s Suffrage Association, running it with great skill. From there, Catt came to the attention of Susan B. Anthony, the Grande Dame of suffragists, who, in 1900, anointed Catt as her successor as President of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Catt was its President when the Nineteenth Amendment was passed in 1920, recognizing women’s right to vote.

Arguably, it was Catt’s stewardship and steady hand that helped unite all the different factions and finally win the vote for women.

Catt would purchase Juniper Ledge, her home in Ossining, in 1919 and live there until 1928 with her companion Mary Garrett Hay:

The story goes that the estate was called Juniper Ledge because of its abundance of juniper trees.

In a 1921 New York Times article detailing a picnic she hosted for 100 members of the League of Women voters, Catt is quoted as saying “I know that the juniper is useful in making liquor, and that is why I bought the place – so no one would have opportunity to use the trees for that purpose.” She served her guests coffee and orangeade.

According to another New York Times article, this one from 1927, Juniper Ledge was quite impressive: “The estate is one of the show places of Northern Westchester, and includes sixteen acres of extensively developed land fronting on two roads. The residence, on a knoll overlooking the countryside, is a modern house of English architecture containing fourteen rooms and three baths. A gardener’s cottage, stables, a garage and a greenhouse are also on the property.” Catt affixed brass plaques with the names of famous suffragettes to fourteen trees – and some of those plaques are reportedly in the archives at Harvard University.

From her Juniper Ledge home, she started the League of Women Voters in order to give women information to help them make informed voting decisions. She also was a big supporter of Prohibition, the League of Nations and its successor the United Nations, spending much of her time on crusades for world peace and international disarmament.

Catt sold Juniper Ledge in 1927 and purchased a home at 120 Paine Avenue in New Rochelle. Sadly, her companion Mary Garrett Hay died shortly after they moved.

Catt lived on, staying active right up until her death in 1947. She and Hay are buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. The inscription on their joint tombstone reads, “Here lie two, united in friendship for thirty-eight years through constant service to a great cause.” (Here’s Catt’s obituary if you want to learn more about her life. It makes me tired just to read about all the things she accomplished.)

So, the next time you drive on North State Road, keep an eye out for this old driveway pillar and know that a very influential and historically important woman lived just up the hill.

CONTROVERSY

We would be remiss if we didn’t address the controversy that has swirled around the US women’s suffrage movement almost since its inception.

Some have perceived that it was a racist one, with white women keeping Black women on the fringes of the movement ostensibly to avoid antagonizing the Southern vote.

Carrie Chapman Catt would address these concerns in a speech she delivered in 1893: “If any say we would put down one class to rise ourselves, they do not know us. The woman suffrage movement is not one for woman alone. It is for equality of rights and privileges, and it knows no difference between black and white.”

However, by 1903, Catt and many of her colleagues would state that the national women’s suffrage movement was solely concentrating on removing the “sex restriction” for voting. They seemed perfectly content to let the individual States to determine what, if any, qualifications were deemed necessary to allow women to vote.

And in 1919, Catt would continue to respond to such concerns, such as those from the NAACP who feared that Black women would not be allowed to vote in southern states if the proposed suffrage amendment did not include specific language to include all races, by repeating “We stand for the removal of the sex restriction, nothing more, nothing less.”[1]

This controversy re-emerged forcefully in 1995, right before Iowa State University (formerly Iowa State Agricultural College) was set to name a campus building in Catt’s honor.

In an article, published in the Uhuru! newsletter of the ISU Black Student Alliance entitled “The Catt’s Out of the Bag: Was She Racist?” sophomore Meron Wondwosen argued that Catt and other white suffragists employed racist strategies to gain Southern support for the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Wondwosen referenced examples of Catt giving lectures in Southern states and stressing that women’s suffrage would reinforce white supremacy, discouraging Black suffragists from participating in marches and rallies, and belittling immigrants and Black people.

After several years of research, reflection and discussion, Iowa State decided not to take her name off the building, saying:

“The crux of the matter is that while Catt made statements that are likely to be considered racist, there is also an abundance of declarations upholding and even defending other races. This duality and implicit contradiction is what makes the work of this committee very difficult—and it is what makes Catt such an ambiguous figure when it comes to questions of racism. It adds layers to Catt, her work, how she viewed the world, and how the world viewed her. These may begin to shed light on how compromises were made to achieve an ultimate goal.[2]

Several of the arguments for removing Catt’s name from Catt Hall were based on Barbara Andolsen’s 1985 book Daughters of Jefferson, Daughters of Bootblacks. Andolsen, a feminist theologian, documented some of the frankly bigoted tactics white suffragists used to win passage of the 19th Amendment. Despite this, however, Andolsen believed most suffragist leaders were “women of integrity” committed to gaining the vote for all women. She argued that these leaders didn’t condone segregation or manipulate racist ideologies out of bad intentions, but out of political necessity in a racist society.

In the 2020 PBS program Carrie Chapman Catt, Warrior for Women, historian Beth Behn explored why Catt, generally a progressive thinker and leader, used racism in the suffrage movement. Behn suggested that Catt felt a sense of urgency, fearing that the opportunity to secure a Federal amendment could close. Behn noted that other developed countries, like Great Britain and France, didn’t grant women suffrage until years later, reinforcing the suffragists’ urgency.

A life-long pacifist, Catt endorsed America’s entry into World War I in 1917 in order to gain President Woodrow Wilson’s support for women’s suffrage. She would spend the rest of her life working for peace and disarmament.

Food for thought . . .

[1] Carrie Chapman Catt, letter to John Shillady, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, May 6, 1919.

[2] 2023 Catt Hall Review Final Report 2023, p. 27; https://iastate.app.box.com/s/rw7igjtl5iet6vb6s3xdu3yfkhqin9ck

Today’s post highlights the life and work of Kathryn Stanley Lawes, known as the “Mother of Sing Sing.”

Now, Kathryn Lawes’ story was actually my entry into Ossining history – when my husband and I first moved here, one of the first things we did was go to the Ossining Library and check out every book we could find about Ossining.

Of course, many of them were focused on Sing Sing Prison. Built by convicts in 1825 using stone quarried on site, it has featured prominently in the history and lore of our town. And Hollywood’s films of the 1930s, starring actors like Humphrey Bogart, Spencer Tracy, and Bette Davis, and where the terms “Up the River,” “The big house” and “The last mile” were coined, helped burnish the myth and mystery of the prison. (Fun fact: Many of these films were actually shot inside Sing Sing’s walls, using real prisoners as extras and sometimes engaging the actual Warden, Kathryn’s husband Lewis Lawes, to play a version of himself. In 1934, Warner Brothers even built a brand-new gymnasium for the prison as a thank-you. Here’s a partial list of films if you’re interested.)

One of the first books I read was Ralph Blumenthal’s “The Miracle at Sing Sing,” a biography of Kathryn’s husband, the progressive and once well-known Warden Lewis Lawes. In charge of Sing Sing from 1920 to 1941, he instituted many reforms and remains the longest tenured prison warden in its history. He also seems to have had the highest profile of any prison warden ever, appearing in movies, giving lectures world-wide, hosting his own radio program, writing books, articles, a Broadway play, and even a couple of screenplays. He also oversaw more executions than any other Sing Sing warden (303, to be precise, with four of them women.)

His wife, Kathryn, was beloved by Sing Sing’s inmates — to the point that they all called her “Mother.” In addition to raising three daughters inside the prison walls, she would regularly go into the prison and visit with the incarcerated. She arranged for every man to get a Christmas present; she would help them write letters to their families; she would even intercede on their behalf with the Warden on occasion.

In 1937, the Logansport-Pharos-Tribune wrote one of the few articles about her and described how she “Took – not sent – food and clothes and money to a family left desolate by the husband’s imprisonment. She saw to it that encouraging letters went to hopeless young criminals. Many, many dollars found their way from her purse to the pockets of newly released men, frightened to face freedom again. . . When a convict’s mother or near relative was dying, the convict was permitted to leave the Sing Sing walls for a final visit. On such occasions instead of going under heavy guard, he was taken in Mrs. Lawes’ own car, often accompanied by the Warden’s wife herself.” [1]

Her youngest daughter, Cherie, recalled how her mother once gave away a favorite dress of hers so that the daughter of one of “the boys” could wear it to attend a high school dance.

Kathryn hosted Labor Day picnics for inmates, Halloween parties for the neighborhood children, and made sure the mess served special meals for Thanksgiving and other holidays.

The inmates knew that they could trust her, with one quoted as saying that telling Mother Lawes something was “like burying it at sea.”

She was especially kind to those in the death house awaiting execution, quietly helping to make their cells brighter, spending hours talking to them, helping out their families – to the extent of putting the families up in her own home as the execution date drew near and arranging their final visits. She also made sure that every prisoner had a decent burial if they had no immediate family.

Little things, perhaps, but important. And so deeply compassionate.

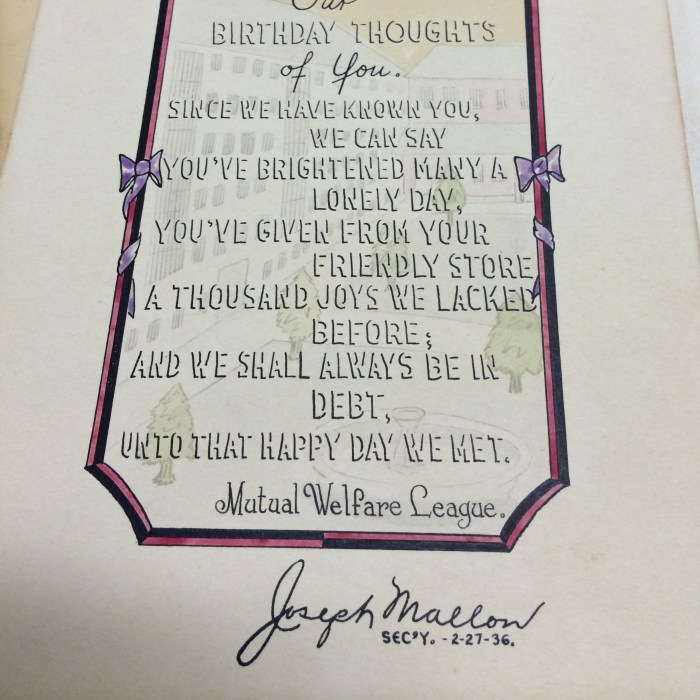

In 1936, the “boys” sent her this handmade birthday card:

Kathryn was born in Elmira, New York in 1885. Born into genteel poverty, she was ambitious and smart. At 17, she took a business course and landed a job as a secretary in a paper company. It’s around that time she met Lewis Lawes, who was working as an errand boy in a neighboring office. But Lewis’ father was a prison guard at the Elmira Prison, so it was rather natural that his son would follow in his footsteps.

Kathryn and Lewis married in 1905 and started their family. Lewis quickly rose through the ranks in the New York prison system first in Elmira, then in Auburn. In 1915, he became Chief Overseer at the Hart Island reformatory, living right in the middle of the facility with Kathryn and their two young daughters. There, Kathryn found time to work with the boys, some who were as young as 10, giving many of them the first maternal attention they’d ever experienced.

Still, it’s quite hard to flesh out Kathryn’s story. She gave very few interviews and those that she did give read like someone wrote them without ever talking to her. Much of what we know about her surfaced only after her mysterious death.

You see, what makes her story so complex (and dare I say compelling?) is that she died at the age of 52 after falling off the Bear Mountain Bridge.

What, you say? But yes, it’s true.

I hate to hijack a Women’s History month post with a true crime mystery, but it can’t be helped.

On October 30, 1937, the New York Times published an article entitled “Wife of Warden Lawes Dies After a Fall. Lies Injured all Day at Bear Mountain Span.” In it, the NYS Police said that she had jumped or fallen from the Bridge. Though conscious when discovered hours later by Warden Lawes, their son-in-law, and Dr. Amos Squire the Westchester County Medical Examiner, she died of her injuries soon after arriving at Ossining Hospital.

A few days later, a follow-up story was published in the Times that quoted heavily from Dr. Amos Squire (the former Sing Sing Prison Doctor as well as Medical Examiner), asserting that he had gone back to the scene of the accident. There, he found “her high-heeled shoes caught between two boards of a walk” and concluded that she had gone hiking, perhaps venturing down the trail to pick wildflowers. He surmised that she had tripped, rolled hundreds of feet down the steep embankment towards the river, breaking her leg in the fall. Then, he asserted, she dragged herself 125 feet to the spot where she was found twelve hours later.

I mean, really. So many things here –

First, how perfectly horrible. What a ghastly way to die. How could this have happened to such a universally beloved woman?

But then, the mind starts to whir . . . Were fifty-two-year-old women in the habit of hiking in 1937? In high heels? And how convenient that her high heels remained stuck between “boards of a walk.” And what about this dragging herself one hundred twenty-five feet southward with a compound fracture to spot where she was finally found? Finally, was it coincidence that the Westchester County Medical Examiner was Dr. Amos Squire, the former Sing Sing prison doctor and old friend to the Lawes’?

There’s so much to unpack. But I’m going to leave it there, for another time.

I’d rather try to concentrate on her life and the good she did in her relatively short time on earth by sharing some of the condolence letters Warden Lawes received. [2] More than anything, they give us a picture of the truly kind, benevolent influence she had on the lives of so many:

Joe Moran, Prisoner # 47-342 wrote “With the passing of dear Mrs. Lawes, the only ray of sunshine ever to be found within the walls of Sing Sing has gone forever. She lent courage to the condemned, she comforted the sick and she brightened the lives of the friendless. The men branded with numbers shall never forget the many kindnesses and acts of charity administered to them by the woman they regarded as their mother.”

Edward McIntyre, a former inmate, said “I don’t believe a kinder soul ever lived. And I know this from watching her making her daily visits to the sick and being at all times ready to help somebody who was in need.”

Even the mothers of inmates sent in condolences: “She was highly appreciated by me because she was kind to the inmates, especially my son. Only two weeks ago he praised her to me. He said ‘Mother, Mrs. Lawes is right fine. Mrs. Lawes always says ‘hello boys’ in a motherly tone. And you know, she does not have to recognize us. But she does.’”

The inmates were inconsolable when they heard the news of her sudden and shocking death. Finally, against his instincts, Warden Lawes was forced to do the unthinkable – open up the prison gates and allow two hundred or so “old-timers” to march up the hill to the Warden’s house to pay their last respects at her bier. Two hundred men walked through the gates to freedom and two hundred men walked back into the prison.

That year, there was no Halloween party for local children, nor any Christmas presents for the inmates of Sing Sing ever again.

To this day, her good works are remembered by preachers and highlighted in their prayers and sermons.

[1] The Whitewright Sun (TX) 11 Dec 1947

[2] Find them in the Lewis Lawes Archive at John Jay College