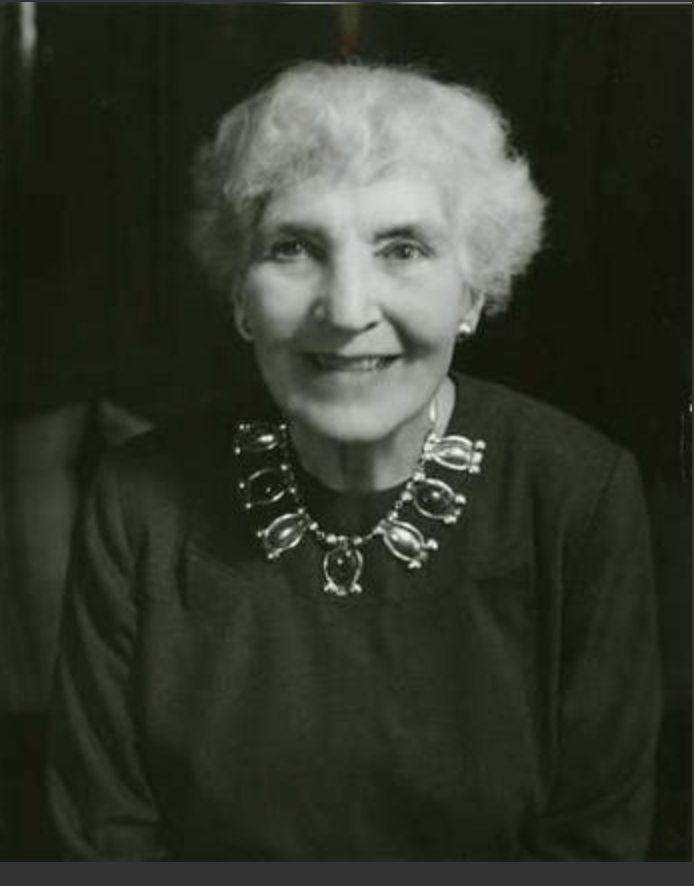

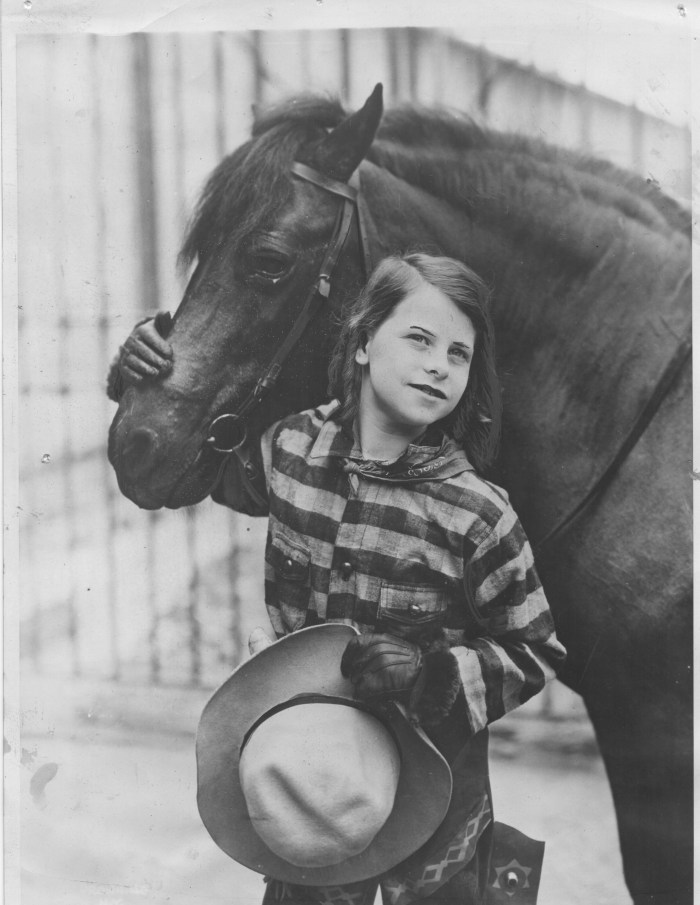

Kathryn Stanley Lawes

1885-1937

“The Mother of Sing Sing”

***Local Connection: The Warden’s House, Spring Street***

(Today, the clubhouse of the Hudson Point Condominiums)

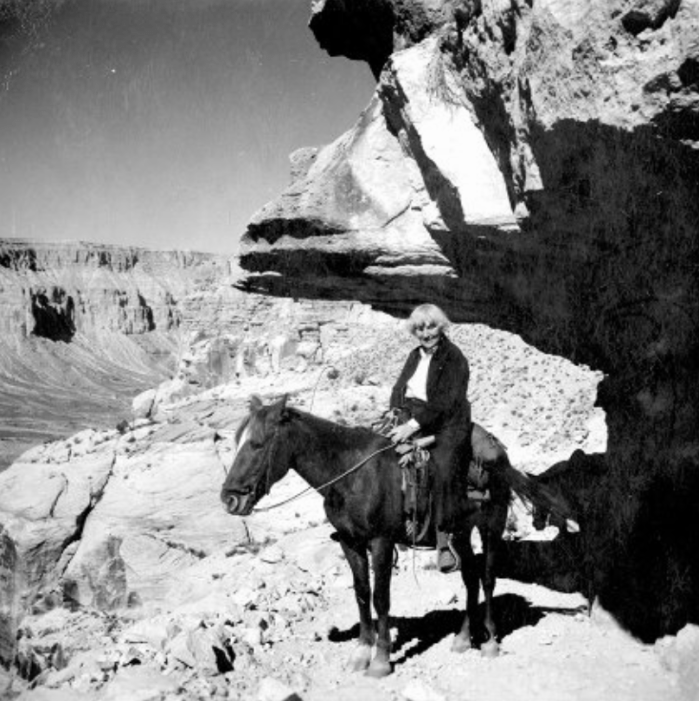

Kathryn Stanley Lawes (1885 – 1937) was known as the “Mother of Sing Sing.”

Wife of Warden Lewis Lawes, the longest tenured Prison Warden in Sing Sing’s history, she arrived at Sing Sing on January 1, 1920 with her two young daughters in tow. Settling into the drafty old Warden’s house situated next to the main cellblock, she would raise her girls (and have a third) within the walls of the prison.

Courtesy of the Ossining Historical Society and Museum

She would regularly go into the prison and visit with the incarcerated. And her quiet kindnesses were the stuff of legend. She would arrange for every man to get a Christmas present – noting that some had never received one in their brutal lives. She would help them write letters to their families. Her youngest daughter, Cherie, recalled how her mother once gave away a favorite dress of hers so that the daughter of one of “the boys” could wear it to attend a high school dance.

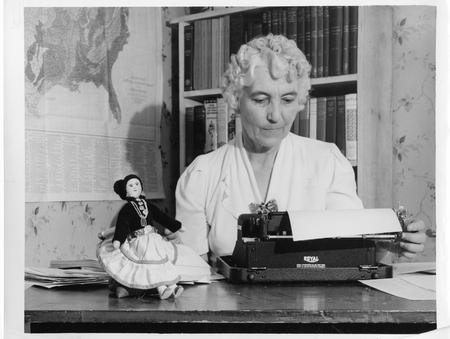

Courtesy of the Ossining Historical Society and Museum

Kathryn hosted Labor Day picnics for inmates, Halloween parties for the neighborhood children, and oversaw special meals in the mess for Thanksgiving and other holidays.

Those incarnated in Sing Sing knew that they could trust her, with one quoted as saying that telling her something was “like burying it at sea.”

In 1937, the Logansport-Pharos-Tribune wrote one of the very few articles about her, saying “When a convict’s mother or near relative was dying, the convict was permitted to leave the Sing Sing walls for a final visit. On such occasions, instead of going under heavy guard, he was taken in Mrs. Lawes’ own car, often accompanied by the Warden’s wife herself.”

She was especially solicitous to those awaiting execution, doing little things to make their cells brighter, spending hours talking to them – sometimes she would even arrange for their families to stay in the Warden’s house as the execution date drew near. She also made sure that every incarcerated man (and women) had a decent burial if they had no immediate family.

Little things, perhaps, but important.

Born in 1885 in Elmira, New York, Kathryn Stanley was ambitious and smart. At 17, she took a business course and landed a job as a secretary in a paper company. It’s around that time she met Lewis Lawes, who was working as an errand boy in a neighboring office.

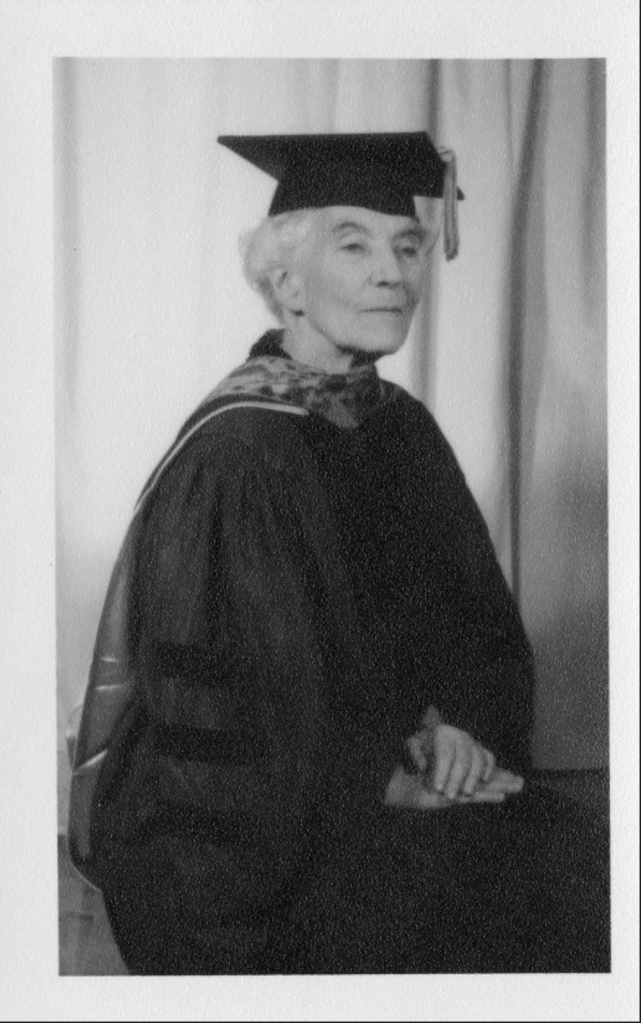

Courtesy of Joan “Cherie” Lawes Jacobsen

But Lewis’ father was a “prison guard” (today the term is “Corrections Officer”) at the Elmira Prison, so it was rather natural that his son would eventually follow in his footsteps.

Kathryn and Lewis married in 1905 and started their family. Lewis quickly rose through the ranks in the New York prison system first in Elmira, then in Auburn. In 1915, he became Chief Overseer at the Hart Island reformatory, living right in the middle of the facility with Kathryn and their two infant daughters. Even then, Kathryn found time work with the boys in the reformatory, some who were as young as 10, giving many of them the first maternal attention they’d ever experienced.

Kathryn would be an essential participant in her husband’s success, helping cement his reputation as a progressive and compassionate Warden.

Still, it’s quite hard to flesh out Kathryn’s story. She gave very few interviews and those that she did give read like someone wrote them without ever talking to her. In fact, much of what we know about surfaced only after her mysterious death.

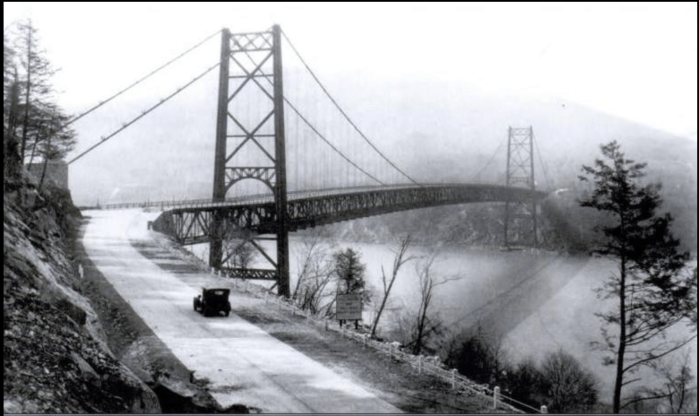

You see, one of the things that makes her story so complex and compelling is that she died at the age of 52 after falling off (or was it near?) the Bear Mountain Bridge.

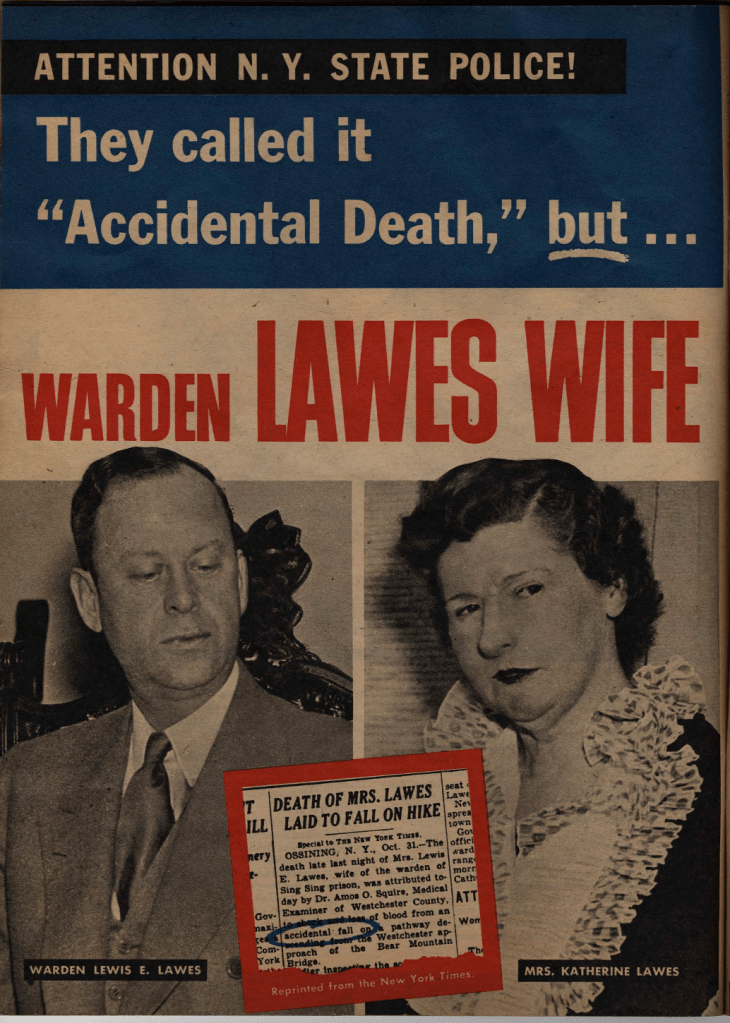

A Mysterious Death

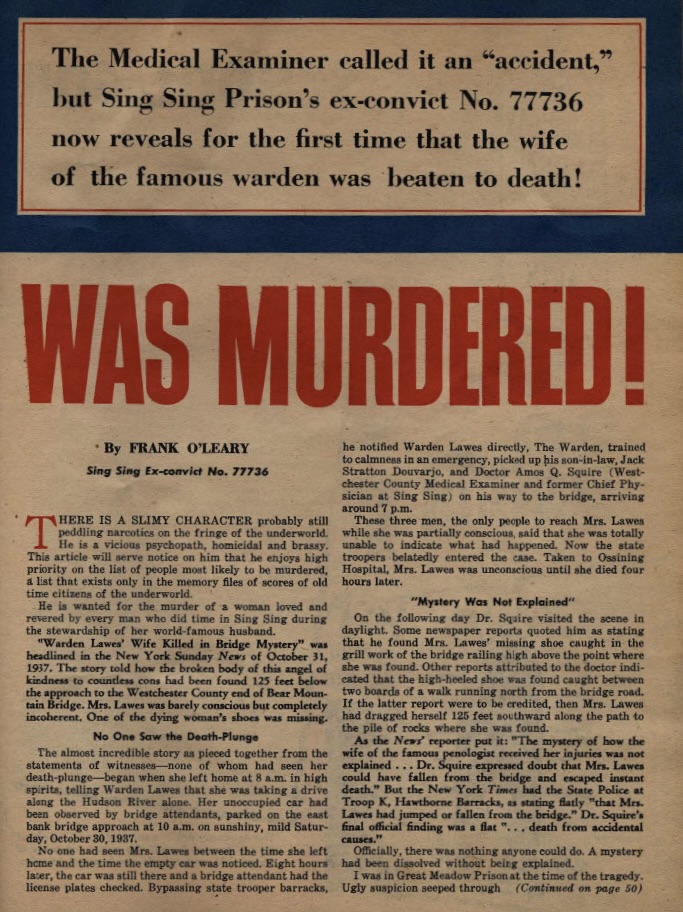

On October 30, 1937, the New York Times published an article entitled “Wife of Warden Lawes Dies After a Fall. Lies Injured all Day at Bear Mountain Span.” In it, the New York State Police stated that she had “jumped or fallen” from the bridge. Though conscious when discovered by Warden Lawes, their son-in-law, and Dr. Amos Squire, she died in Ossining Hospital soon after from her injuries.

A few days later, a follow-up story was published in the Times that quoted heavily from Dr. Squire (the former Sing Sing Prison Doctor as well as Westchester County Medical Examiner). Dr. Squire had apparently gone back to investigate the scene of the accident. There, according to the article, he found “her high-heeled shoes caught between two boards of a walk” and concluded that she had gone hiking, perhaps venturing down the trail to pick wildflowers. He continued, “After falling and breaking her right leg, Mrs. Lawes evidently dragged herself about 125 feet southward along the path to the pile of rock where she was found exhausted.”

The men of Sing Sing were devastated when they heard the news of her sudden and shocking death. Eventually, in response to their entreaties, the prison gates were opened and two hundred or so “old-timers” were permitted to march up the hill to the Warden’s house to pay their last respects at her bier.

(In 1938, the New York Times noted that the “Prisoners of Sing Sing Honor Late Mrs. Lawes” with the installation of brass memorial tablet, paid for by the Mutual Welfare League, a organization of incarcerated individuals.)

Kathryn’s Influence

Fifteen years after her tragic death, Kathryn Lawes’ story continued to capture the attention of the press.

From a March 1953 feature in The Reader’s Digest “The Most Unforgettable Character I’ve Ever Met”, to the July 1956 exposé in tawdry Confidential Magazine below, Kathryn’s life (and death) remained compelling.

Even today, one can find sermons online that praise Kathryn Lawes’ generosity and compassion for those that society would rather forget.