Eliza Wood Farnham

1815 – 1864

Writer

Activist

Abolitionist

Prison reformer

***Local Connection: Matron of Mt. Pleasant Women’s Prison (aka Sing Sing Prison)***

In a society that portrayed the ideal woman as submissive, pure, and fragile, Eliza W. Farnham created her own concepts of female identity. Her theories and actions, occasionally contradictory, offered alternatives to women who felt confined by the limited roles prescribed by their culture. As Catherine M. Sedgwick, a contemporary writer and friend wrote of her “She has physical strength and endurance, sound sense and philanthropy . . . [and] the nerves to explore alone the seven circles of Dante’s Hell.”

Born in Rensselaerville, New York, Eliza Burhans’s early childhood was marked by the death of her mother and abandonment by her father. Growing up with harsh foster parents, she became a self-sufficient, quiet autodidact, reading anything and everything she could get her hands on.

At 15, an uncle would retrieve her from the foster home, reunite her with her siblings and arrange for her to go to school. By 21, she had married an idealistic Illinois lawyer, Thomas Jefferson Farnham, and set off with him to explore the American West.

Eliza would have three sons in four years, though only one would survive childhood. Thomas and Eliza would write up their observations of the West — he would become a popular travel writer of the day, and she would publish her memoir, Life in Prairie Land, in 1846.

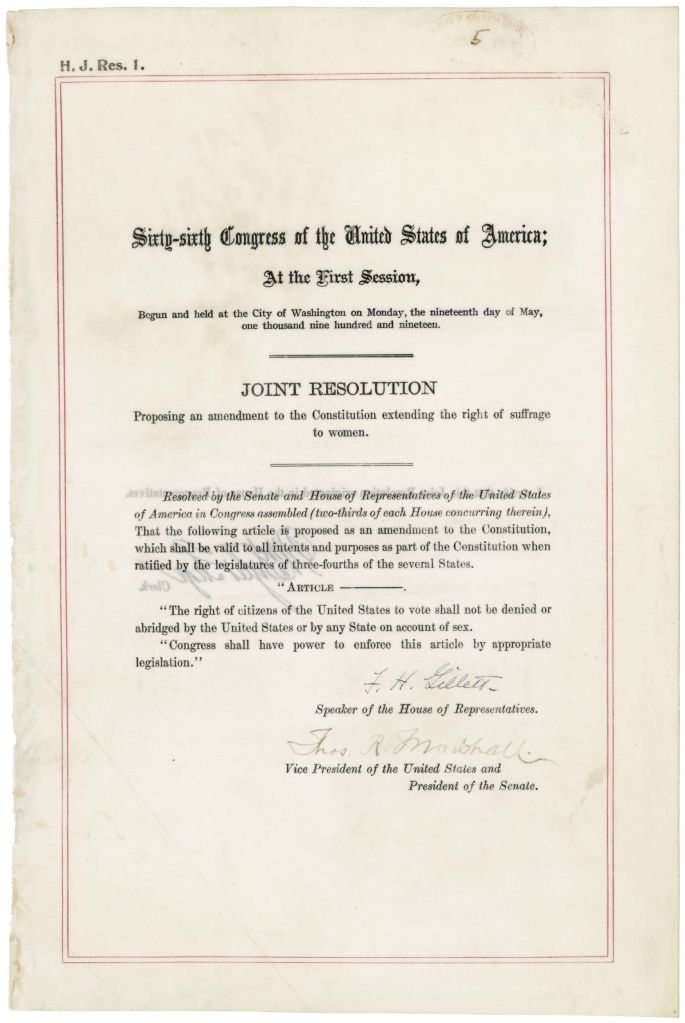

In 1840, the Farnhams returned east and settled near Poughkeepsie, New York, where Eliza became deeply involved in the intellectual and reform movements of the day. An early feminist who believed that women were superior to men, Eliza wrote articles in local magazines against women’s suffrage, believing that women could have a much greater impact as mothers and decision makers in the home. (However, in their 1887 History of Woman Suffrage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony would write that Eliza’s attitudes evolved and that she ultimately saw the necessity of and supported women’s suffrage.)

Eliza also became interested in prison reform at the time, and in 1844 sought and was appointed to the position of Matron of the Mt. Pleasant Female Prison, at the time infamous for its chaos, rioting and escapes, to prove that kindness was a more effective method of governance than brutality.

Courtesy of the Ossining Historical Society and Museum

She instituted daily schooling in the prison chapel and started a small library that allowed each woman to take a book to her cell to read (making sure that there were picture books available for those who couldn’t read.) She also believed that lightness and cheer were more conducive to reformation, and placed flowerpots on all windowsills, tacked maps and pictures on the walls, and installed bright lights throughout. She spearheaded the celebration of holidays, introduced music into the prison, and began a program of positive incentive over punishment. Finally, she fought to improve the food served to the women and ended the “rule of silence”, believing that “the nearer the condition of the convict, while in prison, approximates the natural and true condition in which he should live, the more perfect will be its reformatory influence over his character.” [1]

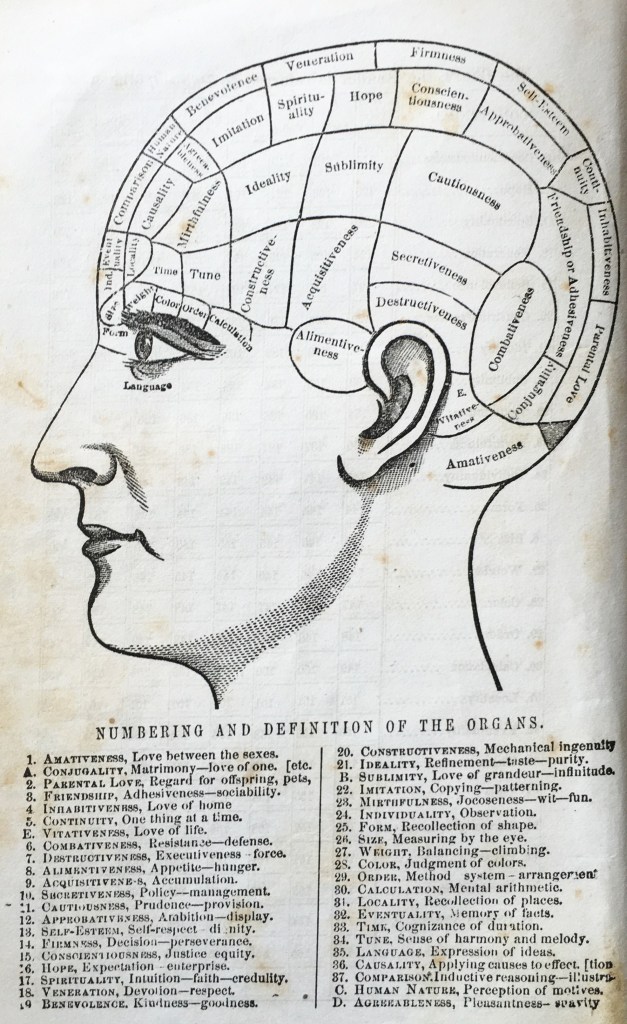

It must be said that her methods were deeply influenced by the now-discounted “science” of phrenology which looked at the correlation between skull shape and human behavior, giving a biological basis for criminal behavior (not, as many religious people believed then, sheer, incorrigible sinfulness.) Eliza would even edit and publish an American edition of a treatise by the English phrenologist Marmaduke Blake Sampson, under the title Rationale of Crime and its Appropriate Treatment. [2]

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Although the mayhem that had plagued previous matrons was significantly reduced, Eliza’s approach was viewed as simply coddling the prisoners. This led to conflicts with several staff members, including Reverend John Luckey, the influential prison chaplain. By 1848, a change in the political landscape installed new prison leadership and she was forced to resign.

She would move to Boston, to work at the Perkins Institute for the Blind until her explorer-husband died unexpectedly while in San Francisco. Eliza went to California both to settle his estate and execute a plan assisting destitute women purchase homes in the West to achieve financial independence. Though that initiative was not successful, Eliza herself bought a ranch in Santa Cruz County, built her own house, and traveled on horseback unchaperoned, among other scandalous things she would detail in her 1856 book California, In-doors and Out.

In 1852, she entered into a stormy marriage with William Fitzpatrick, a volatile pioneer. During this period, she had a daughter, who died in infancy, worked on her California book, taught school, visited San Quentin prison, and gave public lectures.

Divorcing Fitzpatrick in 1856, she returned to New York and began work on what is arguably her most significant work, Woman and Her Era. In it, she would glorify women’s reproductive role as a creative power second only to that of God. She further contended that the discrimination women experienced and the double-standard of social expectations stemmed from an unconscious realization that females had been “created for a higher and more refined existence than the male.”[3]

So, her initial disdain for women’s equality and suffrage stemmed from her unique feminist philosophy that ironically saw women as superior due to their reproductive function, historically something that had always defined female inferiority. Thus, in her world view, why should women lower themselves to the level of men to achieve “equality”?

It’s a fascinating way to look at the world, no?

Eliza would give numerous lectures on this topic before returning to California and serving as the Matron of the Female Department of the Stockton Insane Asylum.

In 1862, she would work towards a Constitutional Amendment to abolish slavery and, in 1863, answer the call for volunteers to help nurse wounded soldiers at Gettysburg.

She died of consumption a year later, likely contracted during her Civil War hospital work.

She is buried in a Quaker cemetery in Milton, New York.

Major Publications:

Life in the Prairie Land (1846) A memoir of her time on the Illinois prairie between 1836 and 1840.

California, In-doors and Out (1856) – A chronicle of her experiences and observations in California.

My Early Days (1859) An autobiographical novel describing Farnham’s life as a foster child in a home where she was treated as a household drudge and denied the benefits of a formal education. The fictional heroine reflects Farnham’s own character as a tough, determined individual who works hard to achieve her goals, overcoming all obstacles.

Woman and Her Era (1864) Farnham’s “Organic, religious, esthetic, and historical” arguments for woman’s inherent superiority.

The Ideal Attained: being the story of two steadfast souls, and how they won their happiness and lost it not (1865) This novel’s heroine, Eleanora Bromfield, is an ideal, superior woman who tests and transforms the hero, Colonel Anderson, until he is a worthy mate who combines masculine strength with the nobility of womanhood and is ever ready to sacrifice himself to the needs of the feminine, maternal principle.

SOURCES

James, Edward T., et al., editors. Notable American Women, 1607-1950 : A Biographical Dictionary. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971.

Wilson, James Grant, et al., editors. Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography. D. Appleton & Co., 1900.

[1] NYS Senate Report, 70th Session, 1847, vol. viii, no.255, part 2, p. 62

[2]Notable American Women, 1607-1950 : A Biographical Dictionary.

[3] Farnham, Eliza W. Woman and Her Era