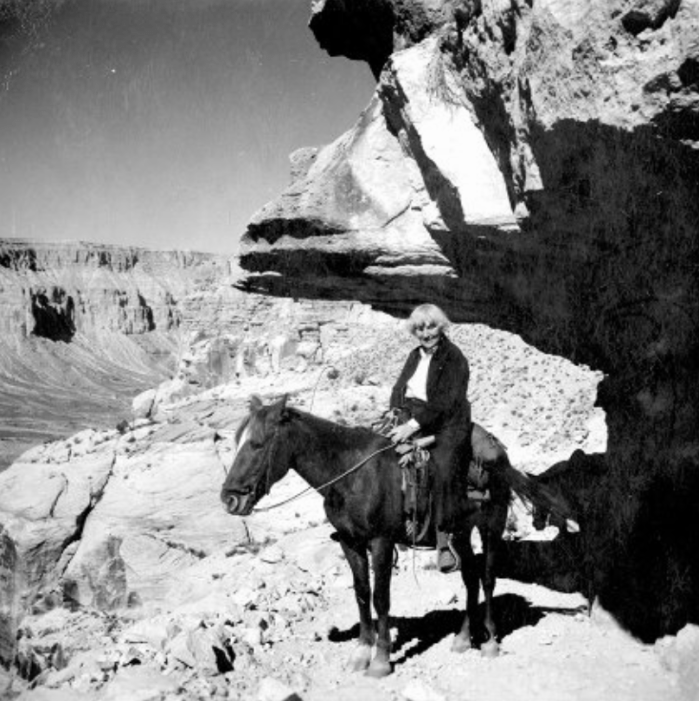

Courtesy Denver Museum Nature and Science Center

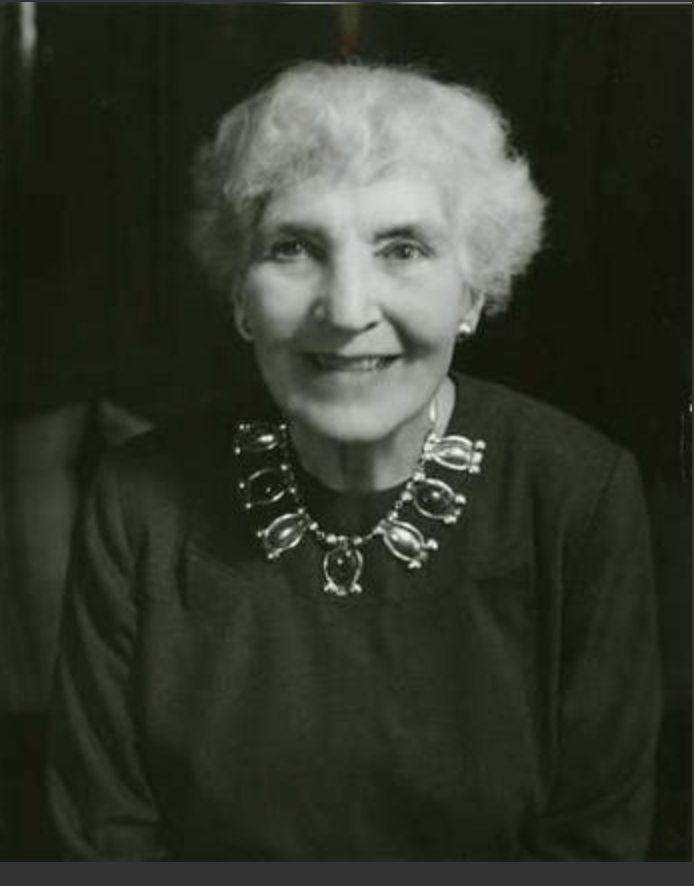

Dr. Ruth Murray Underhill

1883 – 1984

Red Cross Volunteer WWI

Anthropologist

Author

Professor

Television/Radio Host

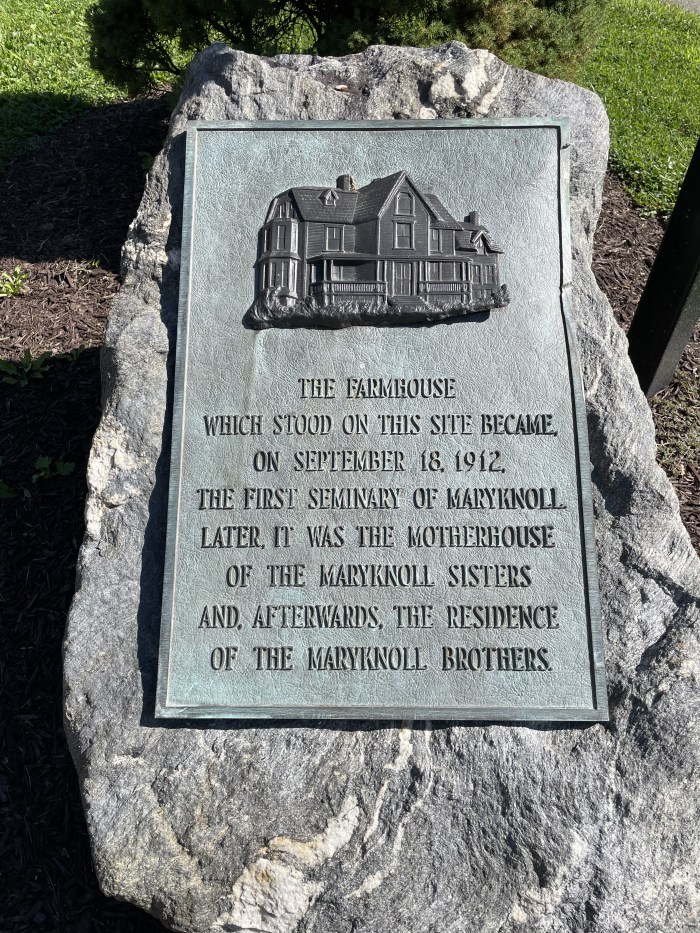

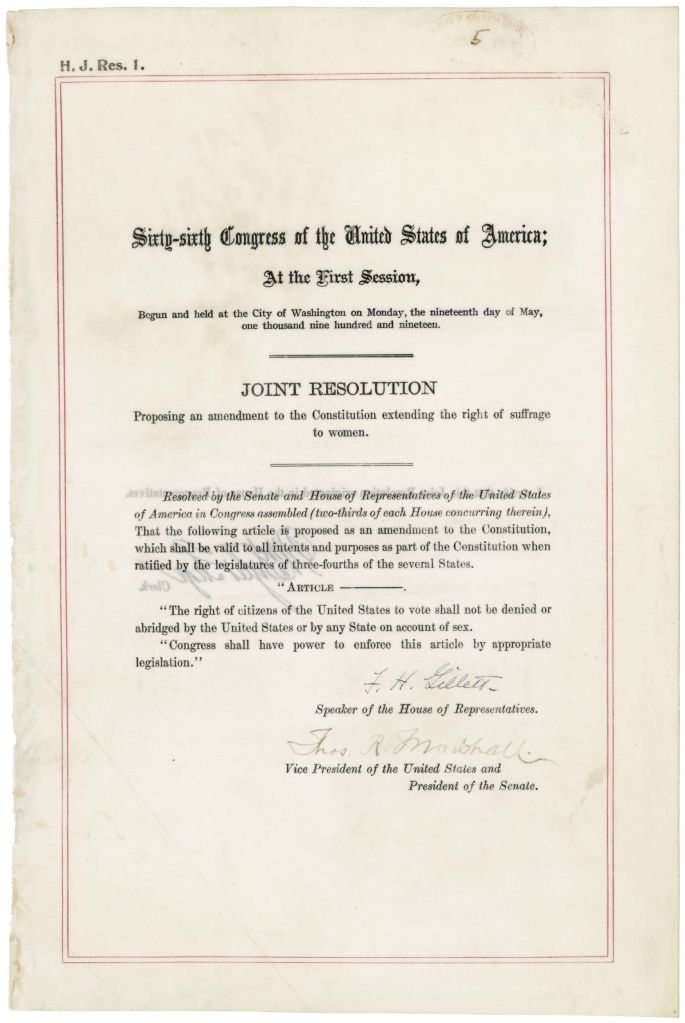

***Local Connection: Linden Avenue***

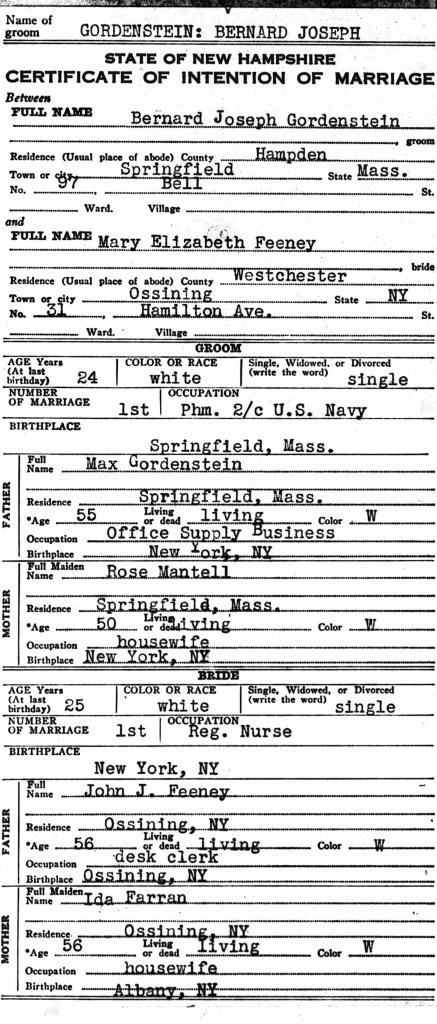

Ruth Murray Underhill was an anthropologist known for her work with Native Americans of the Southwest. She was also a social worker, a writer, a Supervisor at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a professor, and a local television/radio host. Multi-lingual, Underhill spoke several Western languages, including O’odham and Navajo.

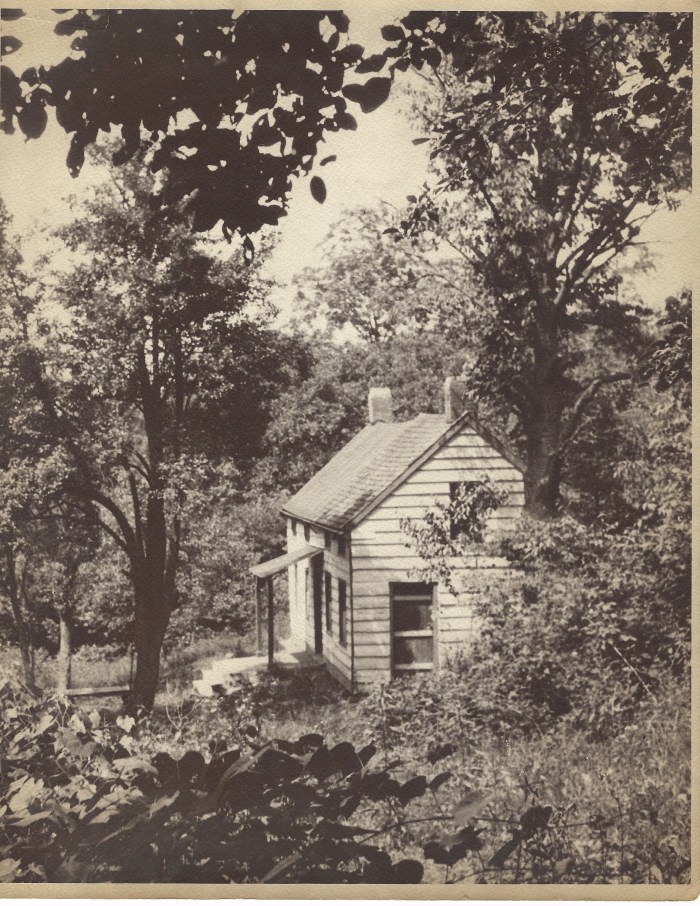

Underhill was born in Ossining in 1883. She grew up on Linden Avenue in the rambling Victorian home built by her father in about 1878. (The building still stands today.)

in front of the family home on Linden Avenue

c. 1890

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

The daughter of Abram S. Underhill and Anna Murray Underhill, her pedigree stretches back to one of the earliest European settlers of this country – Captain John Underhill, who arrived in 1632. And, according to a 1934 article in the Democratic Register, going even further back, the Underhills were related to a William Underhill of Stratford-upon-Avon who reportedly sold William Shakespeare his home.

(It is impossible to ignore the irony that this woman, who spent much of her adult life studying and recording the language and culture of Native Americans, was directly related to Captain John Underhill, a man infamous for his brutal tactics against the Native Americans in the 1600s. He led several bloody massacres and murdered hundreds (if not thousands) of Lenape during the Dutch era in New York State.)

Ruth Underhill attended the Ossining School for Girls (located just across the street from today’s Ossining Public Library):

She would go on to study at Vassar College, graduating in 1905.

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

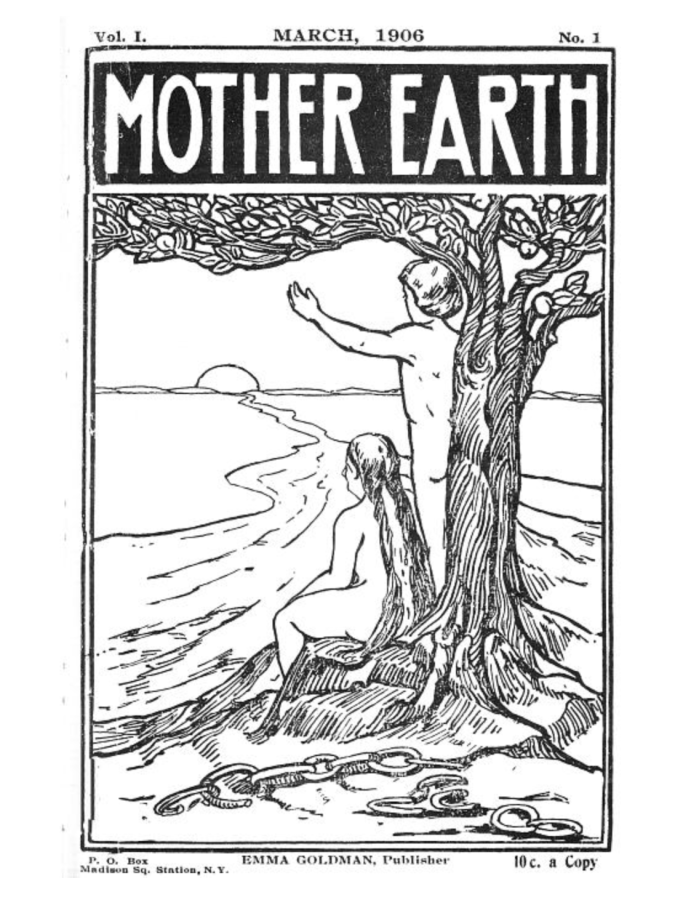

But, as she wrote in her memoir An Anthropologist’s Arrival:

“I did not start with a career and a goal in mind, not even the goal of marriage – for nice girls did not know whether they would be asked or not. I pushed out blindly like a mole burrowing from instinct. My burrowings took me to strange places and now in my last hole I am trying to remember how I bumbled and tumbled from one spot to another. This is the story for those friends who wondered how I could even have started the bumbling, for many girls of my era did not.”

She spent the next decade searching for her calling – briefly serving as a social worker first in Massachusetts, then in New York City, then traveling around Europe with her family. When World War I broke out, she volunteered for the Red Cross, organizing orphanages for the children of Italian soldiers killed in battle.

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

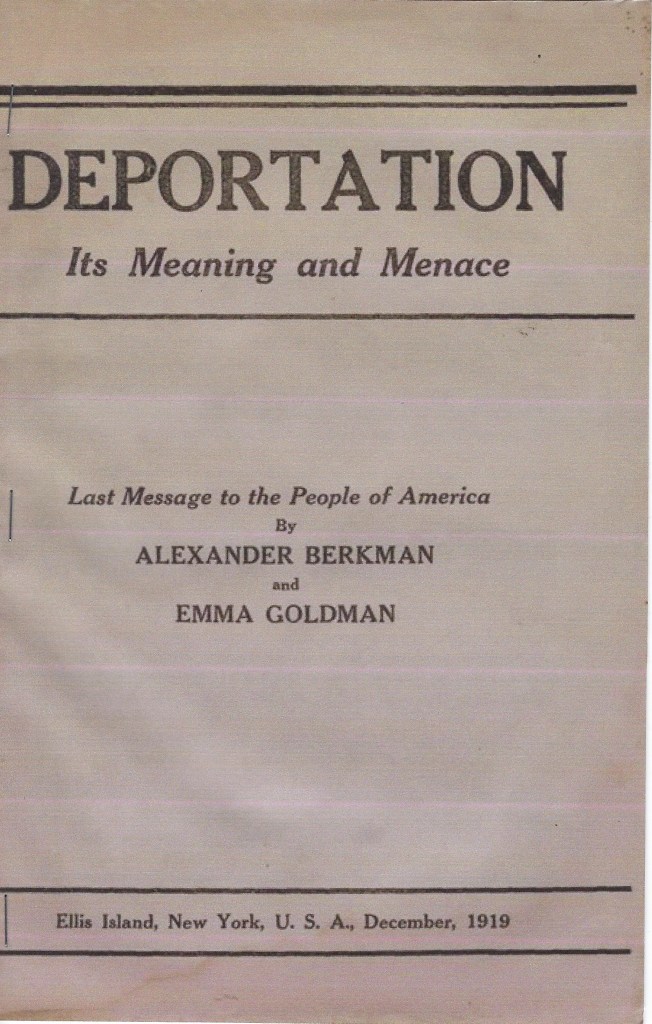

In 1919 she married Charles Crawford, but she described it as a loveless marriage on both sides that would end in divorce a decade later.

At age 46, Underhill went back to school, enrolling in a graduate program at Columbia University.

In her memoirs, Underhill tells the story about how she ended up studying anthropology:

“I am no longer quite sure which departments I visited before anthropology. I think they were sociology, philosophy, and economics. What I said to them in substance was: ‘I find that social work is not doing what I thought it did. I wonder if what you teach would really help me to understand these people. I want to understand the human race. How did it get into the state it is in?’

Upon asking this question of Dr. Ruth Benedict, a well-respected professor in the anthropology department, she found her answer: “You want to know about the human race? . . . Well, come here. That is what we teach.”

At the time, the chairman of Columbia’s anthropology department was Dr. Franz Boas, considered by many to be the “father of modern anthropology.” He seems to have been unusually encouraging towards female students – Margaret Mead and Zora Neale Hurston, among others, who studied with him. Both Boas and Benedict would encourage Underhill to pursue a PhD. [Fun Fact: Dr. Boas is buried in Ossining’s Dale Cemetery.]

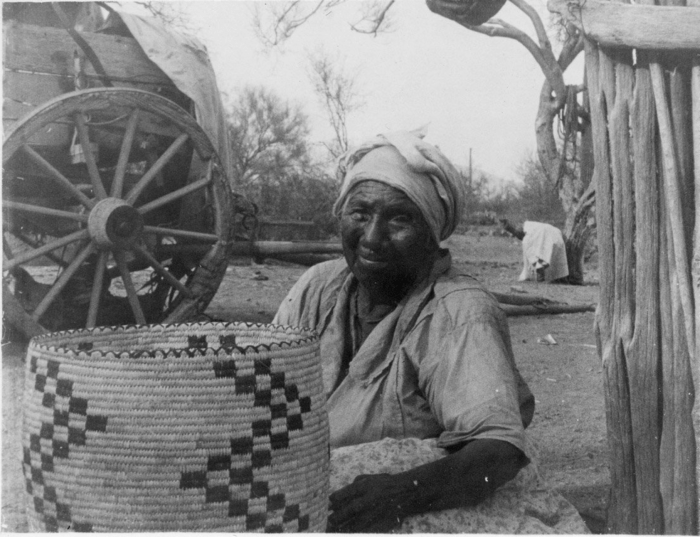

In 1936, Boas financed field work for Underhill to go to Arizona to study the Papago (today known as the Tohono O’odham.) Out of this work came Underhill’s doctoral thesis “Social Organization of the Papago Indians” and the first published autobiography of a Native American woman, Autobiography of a Papago Woman. Living with and studying the Papago in southern Arizona for several years, she became close to Maria Chona, an elder and leader of her tribe.

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

In her book, Underhill documented the rites, ceremonies and history of Chona and her tribe. Underhill even wrote about the rituals surrounding menstruation, which must have been deeply shocking for her readership at that time.

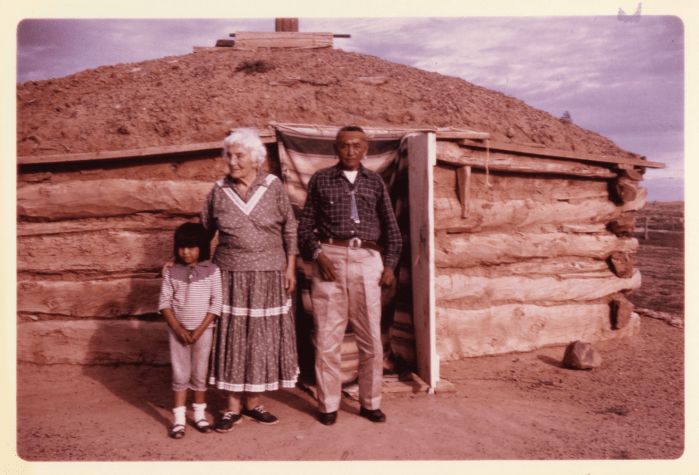

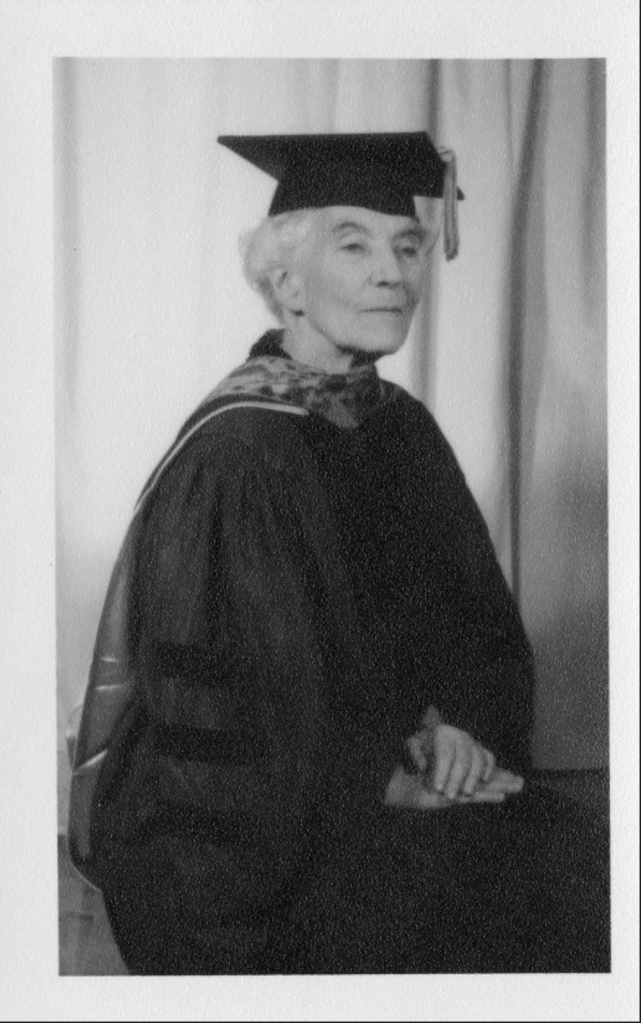

Underhill received her doctorate in 1937 and began studying Navajo culture.

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

From there, she went on to work for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, becoming Supervisor of Indian Education and helping develop curricula for Native American reservation schools.

In 1948 Underhill became a Professor of Anthropology at the University of Denver, but “found the students languid.”

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

She would retire from the University just five years later and travel the world solo.

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

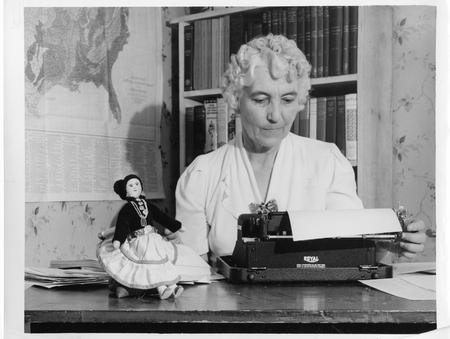

Upon returning home, she would write what is considered her seminal work, Red Man’s America – a textbook on Native American cultures and histories.

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

On the strength of that, she was asked to host a public television program of the same name that ran from 1957 – 1962.

Dr. Ruth Murray Underhill on TV c. 1957

Filming “Red Man’s America” for KRMA-TV channel 6, an educational TV station owned and operated by the Denver Public Schools.

Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

Underhill would stay in contact with the members of the Papago and in 1979, they honored her with the following:

“It was through your works on the Papago people that many of our young Papagos, in search of themselves, their past, their spirit have recaptured part of their identities. Your works will continue to reinforce the true identity of many more young people as well as the old. It is with this in mind that we wish to express our deep sense of appreciation.”

She would die just shy of her 101st birthday.