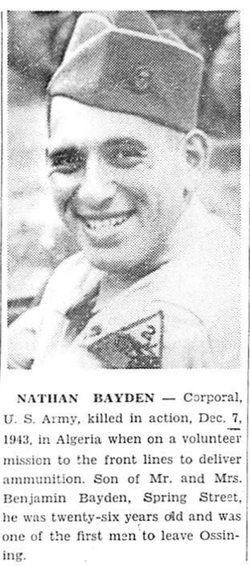

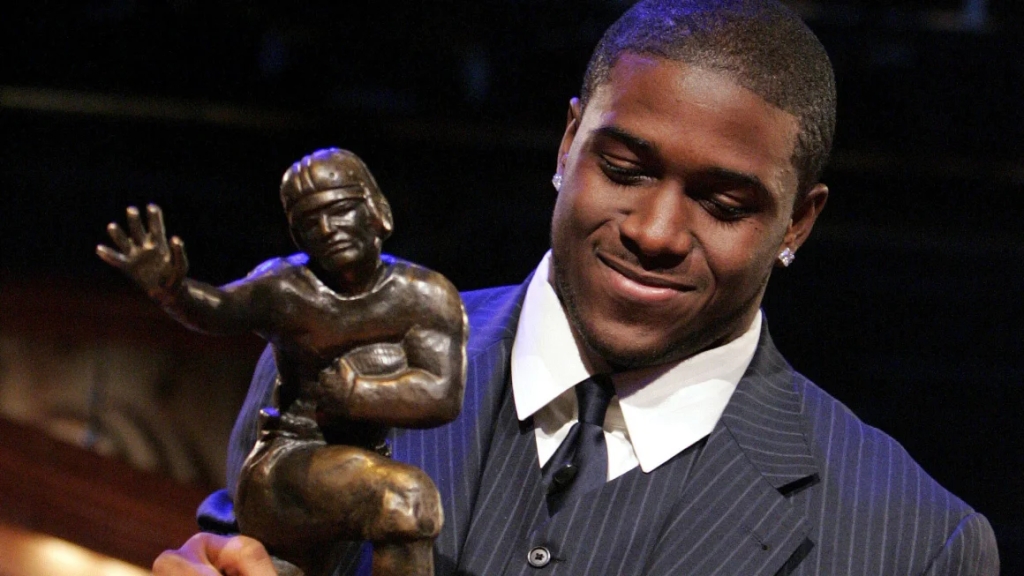

In procrastinating today, and you know I was taking it seriously because I got all the way into the sports section, I saw a story about Reggie Bush, former USC star player, who was just (April 2024) re-awarded his 2005 Heisman Trophy. (Long story short, in 2010, the NCAA decided that Bush had taken impermissible payments as a college athlete and he was forced to give up the award.)

Photo courtesy Julie Jacobson/AP

But it made me think about Ossining’s connection to the Heisman Trophy.

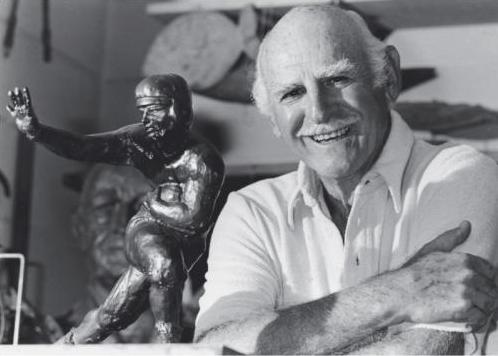

I mean, did you know that the trophy was sculpted by Ossining artist Frank Eliscu?

No, this is absolutely true. Created in 1935 by the Downtown Athletic Club and named in honor of John Heisman, the club’s athletic director, the Heisman Trophy has been awarded every year to the Most Valuable College Player.

Now, I’m not exactly sure how 23-year-old Frank Eliscu landed this as his first commission, but he had graduated from the Pratt Institute a few years earlier, and apparently already had had a one-man show of his artwork, so perhaps that had something to do with it.

The story goes that Eliscu modeled the sculpture on his very buff high school friend, Ed Smith, who was a star NYU running back at the time. [Fun fact — Ed Smith had no idea he’d been so immortalized until 1982!]

Wikipedia tells me that Ed Smith demonstrates “the stiff-arm fend, a tactic employed by the ball-carrier in many forms of contact football” in his pose. But of course you all knew that.

But let’s unpack the Frank Eliscu story, because he is one of many important Ossingtonians who have flown under the radar (to use a cliche, sorry Mr. Gilligan!)

Frank Eliscu was born in 1912 in Washington Heights, NY and lived on West 178th Street with his parents, Charles and Florence Eliscu, who had immigrated from Romania, and two siblings. He attended George Washington High School, where he met the aforementioned Ed Smith, and went on to study at the Pratt Institute, graduating in 1931. After sculpting the Heisman Trophy, he apprenticed with sculptor Rudolph Evans, working with on various projects . Like the Thomas Jefferson statue for the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, DC. (!!)

At some point in the 1940s, he married his wife Mildred, and started studying for a teaching certificate at New York’s Teachers’ College. However, the war upended his plans and he left school in 1942 to serve in the US Army. They first had him working on camouflage and maps, but then transferred him to Valley Forge General Hospital where he worked for the plastic surgery department, modeling replacement features for wounded soldiers. He also invented some unique process to normalize the color of these plastic features and may have even patented it (more research to come!)

Discharged in 1945, Eliscu began teaching at what was then called the School of Industrial Art (today the High School of Art and Design) and taught there until 1970.

According to the 1950 US census, Eliscu lived at 195 Croton Dam Road with his wife Mildred and daughter Norma (OHS ’51) and is listed as a High School Teacher. In a 2001 Ossining High School memory book for the class of 1951, Norma is quoted as saying “though Dad became famous, in Ossining they were just Mr. and Mrs. Eliscu. They knew everyone, spoke with everyone and loved small-town life. I was not aware Dad was famous. He was just Dad who taught school and did some sculptures in the evening in his studio.”[1]

Did some sculptures indeed!

According to his 1996 New York Times obituary, Eliscu designed “many larger bronze sculptures for banks and office buildings throughout New York in the 1960’s and 70’s. From 1962 to 1972 he designed the engravings for six glass works produced by Steuben.”

The New York Times obit continues: “He was the principal designer of the 1974 Inaugural medals for President Gerald R. Ford and Vice President Nelson A. Rockefeller. President Ford later presented a bronze eagle, an enlarged three-dimensional version of the one on the Presidential medal, to Leonid I. Brezhnev, the Soviet leader.”

Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

In 1983, his sculpture “Falling Books” was installed above the entrance of the Library of Congress:

In 1967, Eliscu was invited to become a member of the National Academy of Design (and here’s another Ossining connection — the National Academy of Design was founded in 1826 with the help of Sparta son Frederick Agate.)

So there you go — Frank Eliscu, Ossining sculptor and creator of the Heisman Trophy:

Courtesy of alchetron.com

[1] “Ossining Remembered: 50+ Years Later . . . in the 21st century” edited by Tom Schoonmaker, c. 2001