Courtesy of Kevin Swope

Henrietta Hill Swope

1902 – 1980

Astronomer

Inventor

***Local Connection: The Croft, Teatown, Spring Valley Road***

Henrietta Hill Swope was a quiet, humble, but fiercely driven scientist whose work contributed to our current understanding of the structure of our universe.

Specifically working in the fields of Cepheid variable stars and photometry, her early work showed that that the Earth and the Sun were not at the center of the Milky Way galaxy as previously believed. From there, she surveyed all the variable stars within the Milky Way, thus tracing out the structure of that galaxy, something that had never been done before. She also helped invent LORAN, and contributed to the creation of a new technique to simply and accurately determine the distance of stars and galaxies from Earth.

Born in St. Louis, MO in 1902 to Gerard and Mary Hill Swope, Henrietta came from an extraordinary family. Her father was a financier and president of General Electric, while her uncle, Herbert Bayard Swope, was a Pulitzer-prize winning journalist, war correspondent and newspaper editor. Her mother was a Bryn Mawr graduate who would go on to study with the pioneering educator John Dewey, and later work for Jane Addams at Hull House in Chicago.

Henrietta became interested in astronomy as a young girl, and was taken to the Maria Mitchell Observatory on Nantucket where she heard lectures from Harvard’s Dr. Harlow Shapley and others.

Henrietta went off to Barnard College, where she majored in Mathematics and was graduated in 1925. (She said she chose Barnard because she “didn’t have any Latin. My father didn’t believe in any Latin. He thought I should spend that time on either sciences or modern languages.”[1])

Barnard Class of 1925

Photo Courtesy of Kevin Swope

In 1927, though she had only taken one course in astronomy, a friend alerted her to a fellowship offering for women only sponsored by Dr. Harlow Shapley at the Harvard College Observatory (HCO). She applied and was quickly accepted. (Her initial interpretation was that he was reaching out to women specifically because he “wanted some cheap workers.” Ahem.)[2]

She became Shapley’s first assistant, and while she looked for variable stars on photographic plates taken via the HCO telescope, she earned her Master’s in astronomy from Radcliffe College in 1928.

Looking for variable stars

Courtesy of Kevin Swope

The following year, she became famous when she identified 385 new stars, accurately revealing the composition of the Milky Way galaxy. By 1934, she was in charge of all the Harvard programs on variable stars which were central to much of the astronomical research at the time.

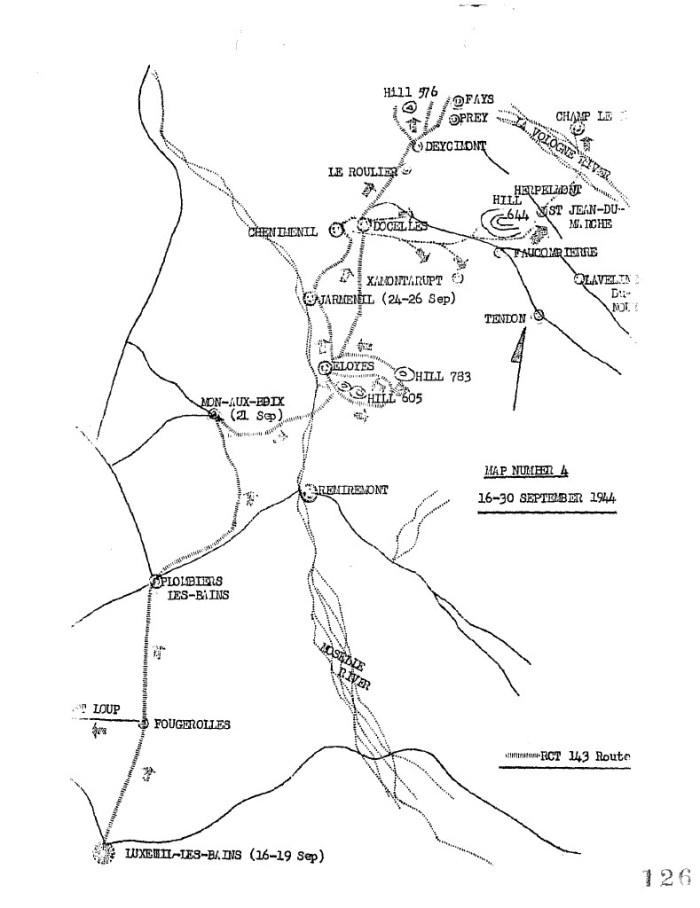

In 1942, she left Harvard to work at MIT in a radiation laboratory, and the following year was recruited by the US Navy to work on a secret project which would come to be known as LORAN (Long Range Aid to Navigation.) This innovative technology allowed navigators to use radio signals from multiple locations to fix a precise position. She was appointed head of LORAN Division at the Navy Hydrographic Office in Washington, DC for the duration of the World War II.

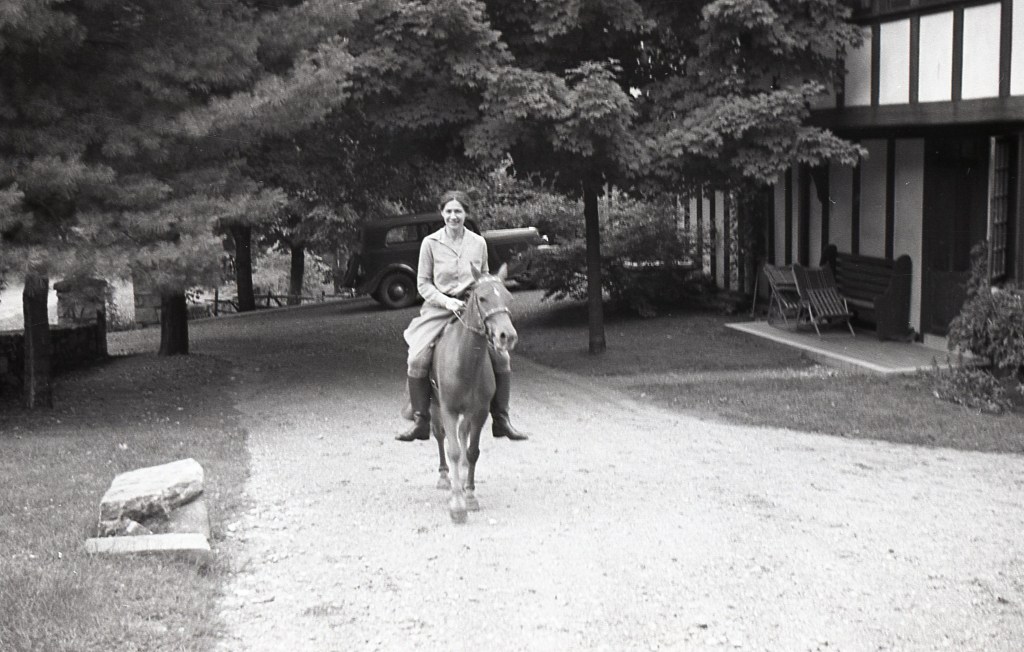

Post-WWII, she would teach astronomy at Barnard College, then relocate to California to work as a research fellow at the Mt. Wilson and Palomar Observatories, as well as teach at the California Institute of Technology (CalTech). She would visit her family’s home The Croft in Ossining a few times a year, and is remembered by a niece as being “no frills. Very sweet, otherworldly, and decidedly bluestocking, none of us knew how accomplished she was or how important her work was.”

Henrietta Swope at The Croft, c. 1930s/40s

Courtesy of Kevin Swope

During this time, Swope’s research focused on determining the brightness and blinking periods of Cepheid variable stars, and the quality and precision of her work allowed other astronomers to use these stars as “celestial yardsticks” with which to rapidly measure celestial distances. Swope herself used them to determine that the distance from earth to the Andromeda galaxy is 2.2 million light-years.

She remained at the Mt. Wilson Observatory and CalTech until her retirement in 1968.

In the 1970s, she donated funds to the Carnegie Institute of Washington to aid in the development of the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile.

The 40-inch Henrietta Swope Telescope began operation in 1971 and though Swope died in 1980, she continues to help people look to the stars.

[1] Interview with Dr. Henrietta Swope, By David DeVorkin at Hale Observatories, Santa Barbara State August 3, 1977. https://web.archive.org/web/20150112054849/http://www.aip.org/history/ohilist/4909.html

[2] IBID