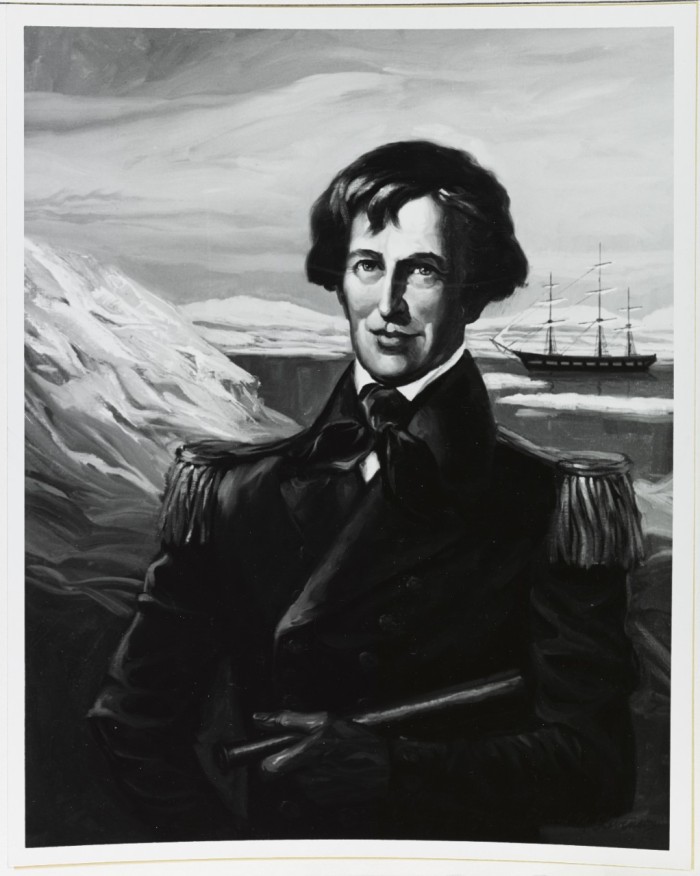

Courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command

Today’s post is the fourth in this series detailing my 2024 voyage to the South Pacific (click to see posts 1, 2 and 3). It will give you a little insight into Lt. Charles Wilkes, the complicated leader of US Exploring Expedition of 1838 – 1842. You’ll also get a glimpse of what life must have been like for Alfred Agate on this four-year voyage to edge of the world with a leader like this.

Joye Leonhard’s biography of Wilkes in Magnificent Voyagers, sums him up as “conceited, domineering and arrogant.” Richard J. King, in his book Ahab’s Rolling Sea: A Natural History of Moby Dick, describes him as “an enormously capable, prolific, pompous prick.” Nathaniel Philbrick notes that Wilkes’ nickname among his officers and crew was “the Stormy Petrel,” a bird so called because its appearance portends stormy, rough weather.

You get the picture. However, without Wilkes’ ambition and determination, the USXX likely would never have left the dock. He was both the best and the worst person to put in charge.

There is a theory, one I can thoroughly get behind, that Charles Wilkes was the model for Herman Melville’s Captain Ahab. Wilkes’ blind intensity, his single-minded drive, and his numerous abuses of power (for which he faced several courts martial upon his return) certainly can be seen in the fictional Ahab’s obsessive pursuit of Moby Dick. We know that in 1847 Melville purchased the entire five-volume Narrative of the US Exploring Expedition (illustrated in part by Alfred Agate!) and quoted from it extensively in Moby Dick.

But let’s dig a little deeper . . .

Charles Wilkes was well-educated, and a talented surveyor/navigator. Born in New York City in 1798, his mother died when he was very young and he and his siblings were initially raised by his aunt Elizabeth Ann Seton. (Yes, THAT Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first American saint, sanctified in 1974!)

Public Domain, courtesy of Wikimedia

However, young Wilkes would get sent to boarding school at the tender age of 5, and by the age of 17 he had joined the US Navy as a midshipman. In between voyages, he would come back to New York City and study math, art and engineering at Columbia University, as well as Hydrology (the measurement and charting of oceans) with Ferdinand Hassler, the first Superintendent of the Coast Guard Survey. Wilkes also befriended the legendary Nathaniel Bowditch, mathematician, astronomer and author of the essential New American Practical Navigator. (Often considered the father of modern maritime navigation, Bowditch’s influence is still felt today, as it is said that every US navy vessel still carries a copy of his book.)

Promoted to Lieutenant in 1826, Wilkes would receive accolades for his excellent work helping to survey and chart Narragansett Bay in 1832 (no doubt in part due to his informal studies with Bowditch.)

I would be remiss if I didn’t include a shout-out here to his wife, Jane Renwick Wilkes. They married in 1826, just before Wilkes was promoted. By most accounts, she was intelligent, savvy, and skilled at diplomacy. The love of his life (it is said,) they had known each other since they were children. She moderated his moods and smoothed the social path for him. Moreover, she was his most trusted confidante, and her absence from his life during his most challenging assignment no doubt contributed to many of his difficulties during the USXX.

Courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command

In 1833, Wilkes would be put in charge of the US Navy Department of Charts and Instruments (later to evolve into the Naval Observatory and Hydrographic Office.) Because of his skill and knowledge, in 1836 he was tapped to help outfit the US XX. He traveled to Europe to purchase the latest in navigational instruments for the Expedition. It wasn’t until March of 1838 that he was given the command – and this only after several others (of higher rank) had been appointed but quickly resigned.

When Wilkes finally left Hampton Roads, Virginia on August 18, 1838, leading the most ambitious exploring expedition ever sent out by the US Government, he was the commander of the USS Vincennes, the flagship of the Expedition. He left behind his beloved Jane, their 4-week old daughter, and three other children. Though communication was extremely uncertain and unpredictable throughout the four-year voyage, Jane and Charles Wilkes would maintain a prolific correspondence. You can read many of these letters held at the Library of Congress here.

The Expedition would test Wilkes in numerous ways – he’d lose two ships, over two dozen sailors and officers to death and desertion, and massacre a village of native people on Malolo Island, Fiji, just to name a few disasters. (Oh yes, more on this Massacre at Malolo to come.) His officers would turn on him, and he would bring charges against at least four of them. They, in turn, filed charges against him and Wilkes returned to the US in 1842 not as a triumphant explorer, but under the shadow of several courts martial. (He was only convicted of one charge, though – illegally punishing his crew through excessive flogging.)

Wilkes would then take over the writing and publishing of the expedition Narrative, with Alfred Agate in charge of the illustrations for the first two volumes. Its first printing was preposterously expensive and only 100 copies were published. However, Wilkes somehow managed to get the US Government to agree to give him the copyright for it, while still getting them pay for the entire endeavor.

Unfortunately, writing was not one of his talents and he mostly cribbed the Narrative from the logbooks of his officers, so the choppy style takes away from the overall excitement of the story. The initial printing of the five portentous tomes were mostly relegated to libraries. Despite this, the Narrative slowly caught the imagination of the public, and went through fifteen printings over the next decade and a half. Should you be interested, you can read the entire thing online here.

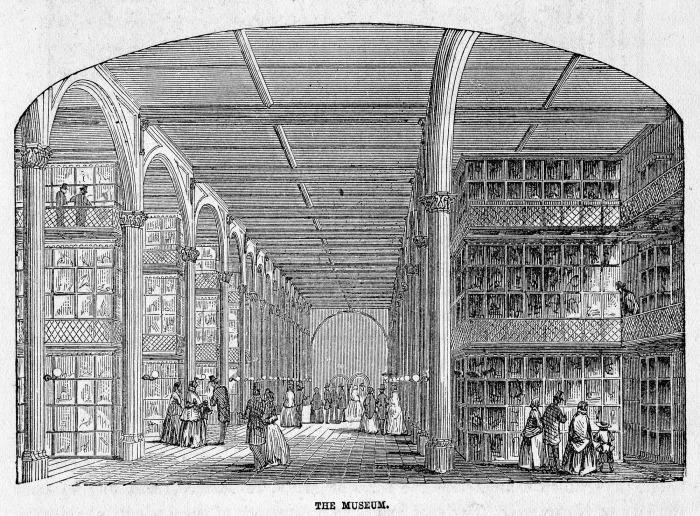

At the same time, Wilkes was preparing the Expedition’s vast collections for display, first at the US Patent Office Building and then as the opening exhibit for the new Smithsonian Museum. It’s thanks to him that many of the live plants brought back survived, and to this day, descendants of this flora can still, remarkably, be found in the US Botanic Garden in Washington, DC.

Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

Wilkes embarked on extensive lecture tours as well, drumming up interest and support for further publications. (In all, there were over 10 books relating to the Expedition and the scientific discoveries it contributed to.)

Wilkes would remain on active duty in the Navy, serving in the Civil War as commander of the USS San Jacinto. In 1861, he almost started a war between the US and Great Britain when he captured two British commissioners from the RMS Trent who had been sent to meet with the Confederates and were on their way back to England. Long story short, President Lincoln had to discipline Wilkes for this (though privately he had been thrilled at the capture and Wilkes had been officially thanked by Congress for his actions.) You can read more about it here.

Unbowed, Wilkes was court martialed a few more times before he was finally retired in 1866, and was at long last promoted to rear Admiral.

He wrote an autobiography (that wasn’t published until 1978,) and died in 1877. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery and on the reverse of his headstone it says “He discovered the Antarctic Continent. January 19, 1840.”

Next post will find us in the islands of Tahiti!

If you haven’t already subscribed and are interested in following this journey, you can do so here: