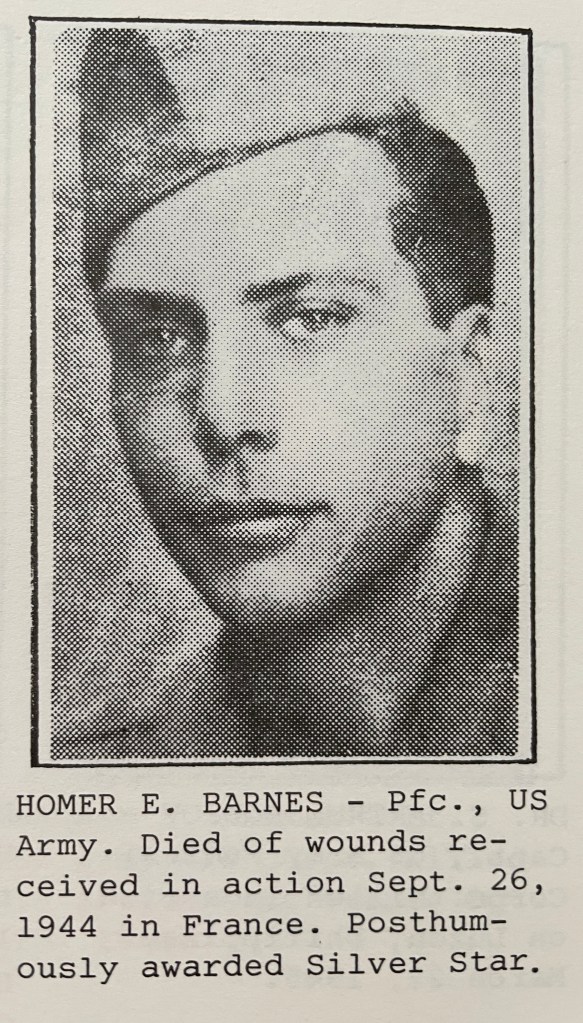

Thanks to the ongoing efforts of the Ossining Historic Cemeteries Conservancy, I recently had the privilege of cleaning this grave, that of Private Homer Barnes, who died in France on September 26, 1944:

I must confess that I chose this grave specifically because it had a Veteran’s flag stuck into the earth in front of it and because the date of death clearly indicated that he had died in WWII. I felt that there was a story to uncover here, and I was not wrong.

Homer Barnes was born in Hamilton, Ontario in 1917 – at the time his father, Dr. Edmund Barnes, was serving as a Major in the Army Medical Corps stationed at Fort Dix during WWI. Homer’s mother had gone home to live with her family while she awaited the birth of her son.

The Barnes family would move to Ossining after the War, and Homer would attend the Scarborough School and then graduate from OHS in 1934.

According to his October 23, 1944 obituary published in the Citizen Register, he then attended Pennington Seminary, New York University, and the New York Technical School. The 1940 census has him working as a “chauffeur, self-employed.”

Homer Barnes registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, and was inducted into the service on December 16, 1942[1] at Camp Upton.

He would serve in the 36th Infantry Division, 143rd Infantry Regiment, Company A, 1st Battalion. (I learned all this from the 36th Division Archive, which also notes that his address was 120 North Highland Avenue, Ossining. Today this is the site of Mavis Discount Tire.)

Private First Class Barnes married Ruth Treanor on April 10, 1943 while he was on furlough from Camp Phillips, Kansas to attend his mother’s funeral in Ossining. Ruth would apparently accompany him back to Camp Phillips and stay there until he went overseas on November 1, 1943. PFC Barnes would see some extraordinarily heavy action, first in Italy, then in France.

Now, I’ve never learned much about the Italian campaign of WWII. Just quickly researching PFC Barnes’ Army service has already taught me more than I ever knew about this part of the war, thanks to the detailed after action reports kept (and digitized) by the 36th Infantry Division archive. Here’s a link to the entire thing, if you’re interested.

I’m not yet exactly sure when PFC Barnes entered the field of battle, but the 143rd Infantry Regiment was engaged in some pretty hot fighting in Operation Avalanche, and the Battles of Monte Cassino, and San Pietro during the last few months of 1943.

By February 1944, PFC Barnes had been awarded a Purple Heart for wounds received while crossing the Rapido River near San Angelo, Italy that January. The after-action report for the 36th Infantry offers some excruciating details about this Rapido River offensive:

“Enemy artillery and mortar fire began falling as the first troops reached the river and when Company “A” [PFC Barnes’ company] sent the first wave across, it met with heavy machine gun fire. . . Reports from men who returned the next day indicate that the German machine gun positions were wired in and the bands of fire were interlocking. Many men were wounded in the lower extremities or the buttocks by low grazing fire as they moved or crawled forward.” (52)

PFC Barnes would have shrapnel lodge in his thigh and end up hospitalized for a month after this.

He returned to the front and continued advancing towards Rome with his regiment. The after-action report almost waxes poetic here:

“Never in the entire Italian campaign was there so brilliant a division operation as that employed by the 36th Infantry Division in flanking the enemy bastion at Velletri…. never before in history had the “Eternal City” been captured from the south and as was evidenced by the swiftness with which the enemy was forced to reel back, he was surprised and outwitted by this brilliant maneuver.” (77)

That said, there was deadly fighting throughout, with the German defense “skillfully located and carefully prepared, with first class infantry and strong supporting fire of artillery.” (77)

However, by June 5, 1944 (yes, the day before the Normandy Invasion D-Day!)

“The 143rd Infantry Regiment moved through the city in all available transportation, past the Colosseum, the Ancient Forum, Vatican City and splendid Saint Peter’s Cathedral, through the Arch of Triumph of the Caesars amid cheering throngs of Romans throwing garlands of flowers – greeted as true liberators in a grandiose but sincere reception. No infantryman will forget this experience and he may well be proud to remember it. Following this triumphal turn through Rome, all troops of the 143rd Regiment terminated their gruelling advance, and took a well-deserved rest, bivouacking on the outskirts of the city.” (78)

I sincerely hope that PFC Barnes got to experience this – it must have been rewarding and remarkable. Because after a short break, his regiment would continue to pursue the Germans north. As Captain Douglas Boyd, the Adjutant of the 143rd Infantry Regiment and author of this part of the after-action report writes: “There is no praise too great for the officers and men of the regiment who uncomplainingly, with true soldierly spirit and without regard to self, fought their way those 240 miles in hot pursuit of the enemy.” (90)

After this, PFC Barnes and the 143rd engaged in a Normandy-like invasion of beachheads in Southern France, landing between Cannes (to the north) and Saint-Tropez to the south. PFC Barnes would spend the last month of his life engaged in daily life and death battles, pushing up into the French Alps and encountering stiff resistance from German troops the whole way.

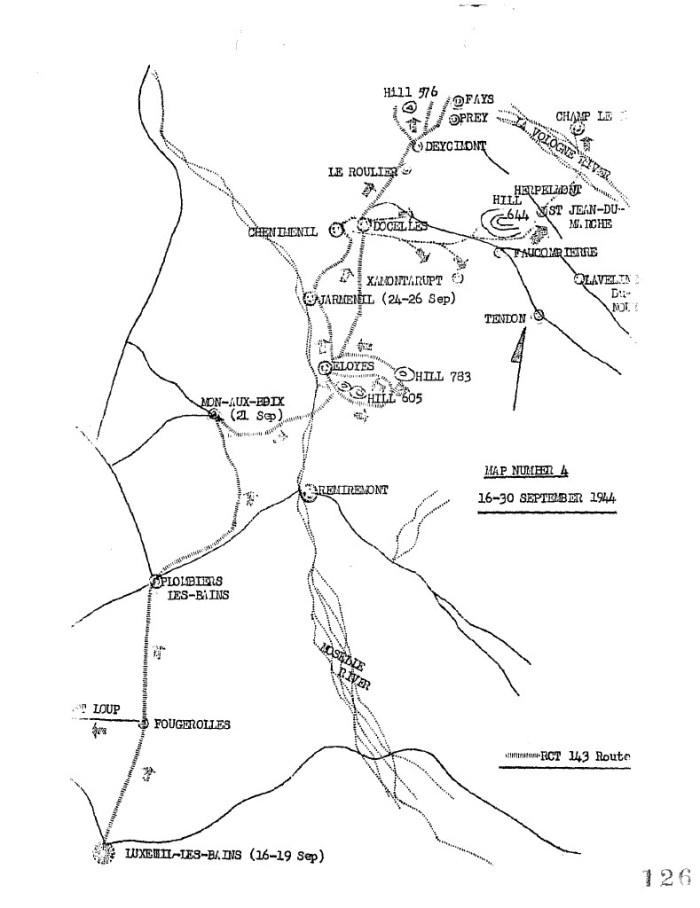

While I can’t be 100% certain, it seems that the last fight PFC Barnes engaged in took place around the Moselle River near a town called Remiremont.

The after-action report describes the attack as follows:

“The 143rd began to cross the Moselle River in a column of battalions, the troops waiting and hand carrying their weapons . . . The 1st Battalion – [PFC Barnes’] moved towards its objective, Hill 605 southeast of Eloyes, while under enemy artillery, mortar and machine gun fire. The enemy, approximating battalion strength, engaged the first battalion units in a fierce fire fight. During the night of 21 September 1944, a company of Germans infiltrated Company A’s [PFC Barnes’] positions, and at the dawn of 22nd September, bitter hand to hand fighting ranged until the Germans were cleared.” (133)

PFC Barnes died on 26 September 1944 from wounds received on 22 September, so I’m going to make the assumption that he was wounded in this “bitter hand to hand fighting.”

He would be posthumously awarded the Silver Star for gallantry and this decoration would be presented to his two-year-old son, William E. Barnes.

[1] October 23, 1944 obitiuary published in the Citizen Register

Love this Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Thank you for a very well written and researched articleYour enthusiasm for history is very evident.reminds me a bit of Ken Burns, whose enthusiasm has turned into a major source of historical productions.Keep up the good work!Dave kriegerSent from my iPad

LikeLike

What a nice way to bring this young man’s spirit back to life for a few moments.

Chris

LikeLike

Was Barnes Road named in his honor?

Brian Doyle

LikeLike

I don’t believe so, as I think that street name pre-dates his death, but I need to do further research.

LikeLike