I can’t quite believe it’s taken me this long to write about Teatown Lake Reservation.

Talk about ignoring things in your own backyard! It’s not only a wonderful organization that has provided exemplary stewardship of the land, but it’s also a goldmine of history.

If you know where to look, of course.

Now, I have of late become a little more interested in pre-history – I mean geologic history, the kind that involves rocks and . . . well, rocks. It is truly the history before humans. See here for more.

(Also, see the first chapter of my new book Croton Point Park: Westchester’s Jewel on the Hudson)

But I’m not going to go back to the Precambrian epoch. I mean, I could tell of gneiss and schist and Ossining marble, of ancient continental plates, ever shifting and buckling up mountain ranges. Of Pangaea and volcanoes and ice sheets . . . but already, I feel your attention begin to wane.

No, I have to admit that my interests lie in people – how they lived, what they ate, what they wore, what they did. How different yet similar we are. And, of course, how we got to where we are today.

Teatown has all of this – characters and stories, and a long, long history that can indeed be traced back to rocks and magma.

So let’s start from today, and go backwards, investigating the world of Teatown from 2022 all the way back to – well, I guess the history of the rocks and ice I disparaged above. Or at least until I get bored.

First, no discussion of Teatown would be complete without calling attention to Lincoln Diamant’s excellent book, Images of America: Teatown Lake Reservation.

You can find it in our local libraries, pick it up at the Teatown gift shop, at any number of our local bookshops or, if you must, buy it online.

(Full disclosure, I have plucked much of my research for this post out of Diamant’s book.)

So, what is Teatown? (And how did it get its name?)

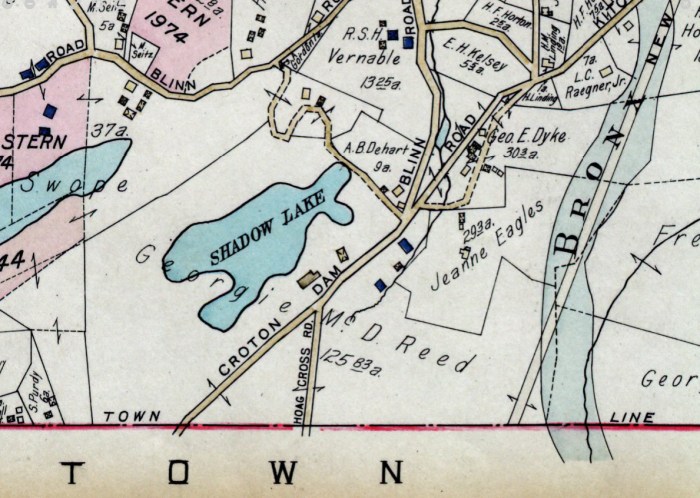

Today, 2022, Teatown Lake Reservation is a non-profit nature preserve with miles of trails, native plant exhibits, and a small wildlife refuge. Much of the land that constitute today’s Teatown was owned by Gerard Swope, Sr. and his wife Mary and inherited by their five children. They created Teatown Lake Reservation in 1963 to honor their parents and it has been thriving and growing ever since.

Gerard Swope was president of General Electric from 1922 – 1945 and was a well-respected businessman and labor reformer. He also worked in the Roosevelt administration during the Depression to aid with the economic recovery.

In 1922, Swope purchased the main house, the outbuildings and various parcels of land from the estate of Dan Hanna. In 1924, the Swopes created Teatown Lake, by building the small dam still found at the far side of lake.

I must note that from October – December 2022, Teatown had to do some extensive rebuilding of the dam and in the process, drained the entire lake. Here are some photos and look – you can see the remains of 18th/19th century stone walls still stuck in the mud.

And here are some pictures of the diggers and backhoes at work rebuilding the dam and installing a new pump.

But back to the exciting title search — in 1919, Dan Hanna purchased the land. He was the owner and publisher of the Cleveland News, as well as being a coal industrialist from the Ohio region. If you’re a serious political history buff, you might find it interesting to learn that he was the nephew of Ohio Senator Mark Hanna, the Karl Rove (or Kellyanne Conway) to our 25th President, William McKinley.

Dan Hanna was referred to as a “Cleveland Millionaire,” in a 1916 New York Times squib about his third divorce. (Is that a sniffy New York Times way of saying he wasn’t up to New York social standards?) He then swiftly remarried Molly Covington Hanna in the same year. There are other newspaper clippings I’ve seen that were positively salivating over his marital career (“Dan Hanna is some Marry-er” winked the Lexington Herald-Leader in December of 1916).

At his death in 1922, according to the New York Times, his estate was valued at $10,000,000. He was also noted as having four infant sons. Considering that he married Molly in 1916 and she was 47 at the time, that is either surprising or simply incorrect. Yet this curious 1923 article describes a chaotic life after she was widowed, despite the 978 acre estate on Makeenac Lake in the Berkshires that she received as a wedding gift from Hanna.

Continuing on back in time, the previous owner, Arthur Vernay, purchased the parcel in 1915 from the Hershfeld estate. Vernay was one of those wealthy men with a fascinating variety of interests and hobbies – apparently he was a very successful antiques dealer in Manhattan who was also an enthusiastic big-game hunter in the style of Teddy Roosevelt (and who also donated many carcasses to the Museum of Natural History. Apparently you can still find his name on a plaque in the Roosevelt wing there today.)

Vernay was responsible for building many of the Tudor-style structures that still stand today. Those office buildings by the parking lot? These were the old stables and outbuildings of the Croft, Vernay’s matching Tudor-style mansion that stood across the street until it was demolished in 2019. The Croft supposedly contained imported genuine antique English interiors (a fireplace in there was said to be from the 1300s!) I mean, considering that Vernay dealt in antiques, that seems possible.

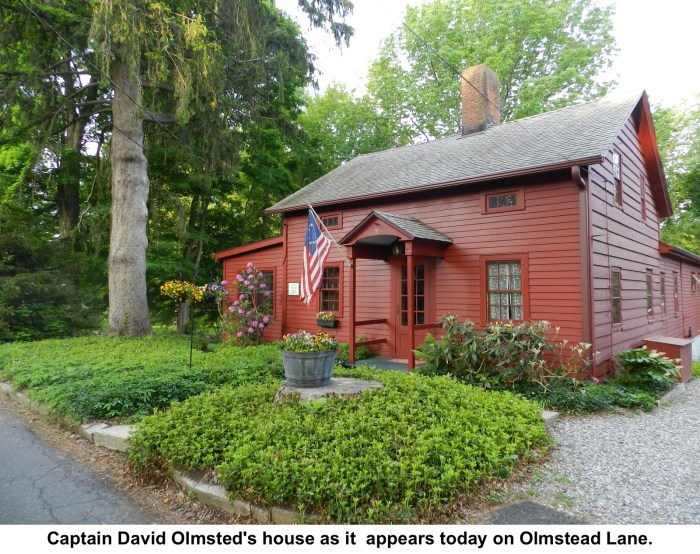

Now, here’s where it gets complicated. Before 1915, Teatown was part of a series of parcels that had at one time all been owned and farmed by the Palmer family. The Palmer connection goes back to 1780, when William Palmer purchased a fairly large tract of land from Pierre Van Cortlandt. Palmer lived at 400 Blinn Road (so named in the 20th century by actor Holbrook Blinn) and seems to have run a successful dairy farm. (Lincoln Diamant says that #400 was a converted dairy barn. But Diamant also says that #400 was a house built by the Van Cortlandt’s in 1740. I’d be interested to know which is the truth.)

In 1826, William Palmer gives several plots of land to his son Robert, who would build himself a farmhouse nearby at 340 Blinn Road.

A few years later, William Palmer would give another plot to his son John, who apparently lived in a farmhouse on or near today’s Teatown administration building. His barn is said to have been on the site of the maple sugaring shed. And the lake? That wasn’t there at all – it was in fact a Big Meadow (so noted on maps of that era.)

At some point, son (or grandson?) Richard Palmer also received a plot of land – this one all the way over by Teatown Road. In fact, if you walk along the Lakeside Trail, crossing the two Eagle Scout-built bridges built by Troop 18 scouts Michael Pavelchek and William Curvan . . .

. . . you’ll eventually come upon some crumbing stone foundations which are all that’s left of Richard Palmer’s farmstead. The buildings were supposedly standing until 1915, and I have even heard that daylilies are still seen to bloom at the site on occasion (though I’ve never managed to see any.)

Other plots of land were sold to non-Palmers, one of which still whispers to us when the leaves are down. As you’re walking on the Lakeside Trail, right next to Spring Valley Road, you might notice a pile of stones. These are the foundation of Kahr’s farmhouse, located at 1685 Spring Valley Road.

And if you walk a little farther and look carefully, you can even see what I believe is the original well for this farmhouse:

Are your eyes glazed over yet? Stay with me a bit longer and I’ll tell you how it got its name AND make the connection all the back to the first people – I’ll be quick, I promise!

How did Teatown get its name?

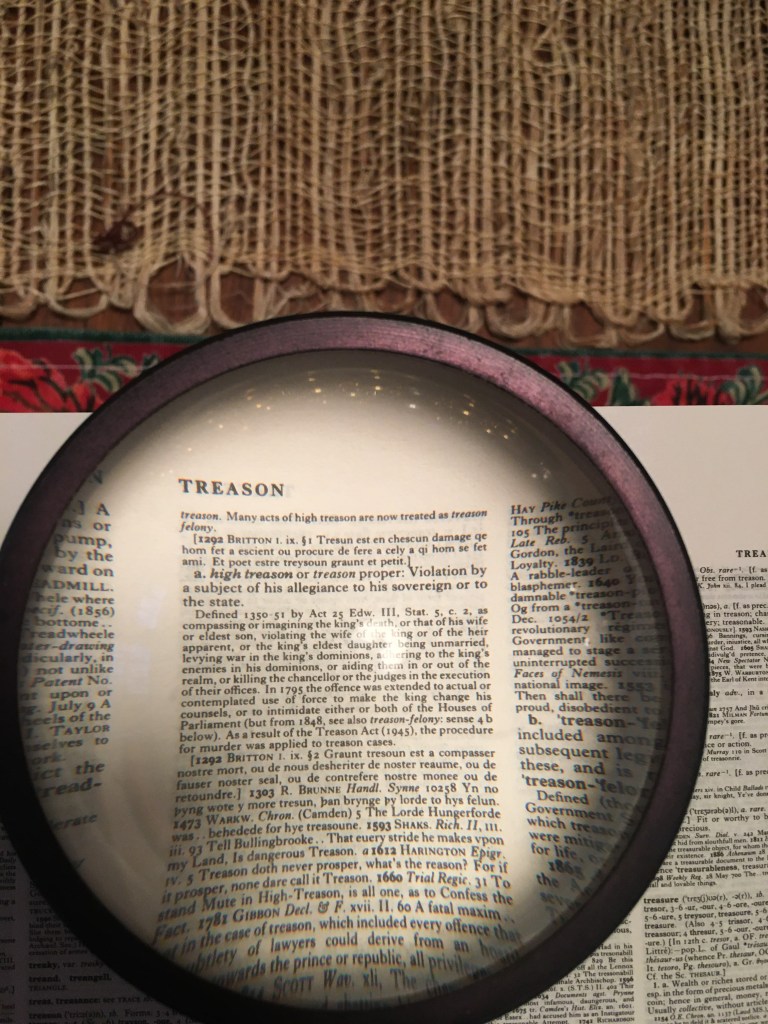

The story goes (and it comes from the aforementioned Mr. Diamant) that during the American Revolution a grocer named John Arthur moved up from British-controlled Manhattan to the Neutral Zone of northern Westchester. Gossip ensued, and it was bandied about among the local women that Mr. Arthur had several chests of tea in his possession. Now tea was as precious as gold then (remember the Boston Tea Party??) and Arthur was a prudent businessman who hoped to sell his tea for whatever the market would bear. Well, this market of tea-deprived farmwomen was no match for him – they ransacked his farmhouse and found the tea. He finally agreed to sell it to them for a reasonable price and so Teatown was born.

(I will not waste words poking holes into this story as I do not have a better one to offer in its place.)

Moving still further backwards . . .

In 1697 Stephanus Van Cortlandt is awarded a royal patent from King William III for 86,000 acres that ran from today’s Van Cortlandt Manor in Croton all the way up to Anthony’s Nose and inland almost to Connecticut. Stephanus died in 1700 and it was up to his widow Gertrude and about 100 tenant families to farm and maintain the land. (Well, I’m pretty sure Gertrude wasn’t doing any hoeing. . .)

Now, before 1609, when Henry Hudson sailed his Half Moon up the river, the area was home to Algonquin-speaking indigenous people related to the Mohicans, Munsees, Wappingers and Delawares. The Sint Sincks and the Kitchawan were two tribes that likely used the Teatown area as their hunting grounds.

It’s not entirely clear to me when/how Stephanus Van Cortlandt wrested the land away from the Indians. I have not researched this thoroughly, so can’t say whether or not there’s a “deed of sale” exchanging some rifles, kettles, trade cloth and tankers of rum for the land in the 1680s or so.

Going back even farther, say about 10,000 – 15,000 years ago, people were following the retreating glaciers and first coming into the area from the south and the west.

Think about that — our area has only been habitable fairly recently. Consider that the most recent ice age, of the Quaternary Period, began over 2 million years ago and it wasn’t until about 25,000 years ago that humans and animals could even have survived. It is, as Town of Ossining historian Scott Craven likes to say, just a geological snap of the fingers!

So there you have it – a thumbnail history of Teatown from November 2022 to 2 million years ago. While this is by no means in-depth reporting, I hope it will inspire you to dig deeper.