This is the 2nd post detailing my 2024 voyage to the South Pacific. (Thanks to all of you who responded to my last post asking for more info!)

Herewith I shall answer the essential questions. To wit:

- What is it that I’m doing?

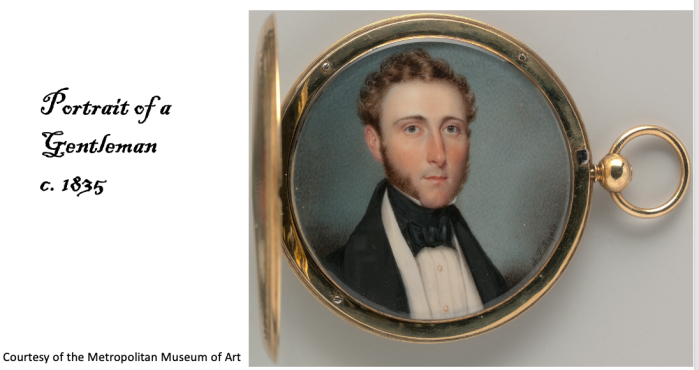

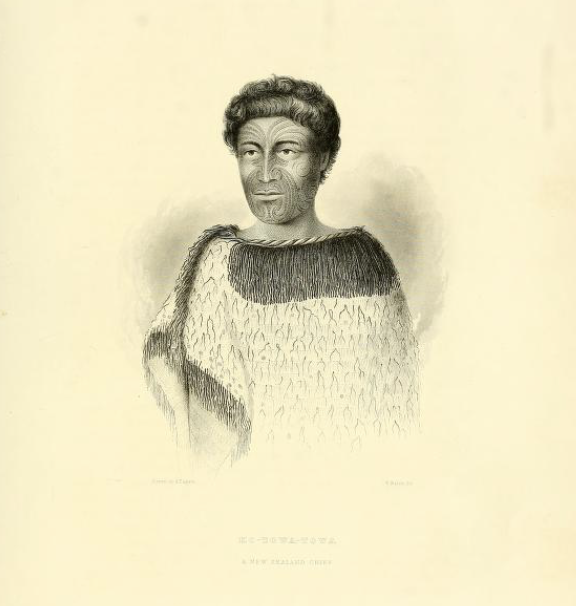

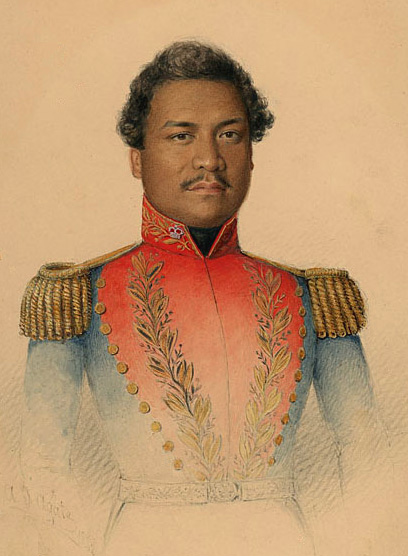

My primary impetus for this expedition is to follow in the wake of the artist Alfred Agate, born in Sparta village (today’s Ossining) in 1812.

I am constantly amazed by how the local can connect us to the world. I mean, local history is the bridge that gets you from your neighborhood in Ossining to Tahiti, to Fiji, to Antarctica and beyond. Plus, let’s face it, history is often taught in a rather remote way, dealing with Great Men, dates, wars and empires – things that are grand and far removed from our everyday experience. I think the more we can weave these threads of local connection into the global fabric, the more interesting history becomes, and the tighter our understanding and bonds become with people and cultures around the world.

It’s my hope that I can make the life of Alfred Agate and his experience on the US Exploring Expedition of 1838 – 1842 not only more immediate, but also relevant to our understanding of the world today. Because understanding the past can help us learn from it and move this knowledge forward to do things better in the future.

2. Where am I going?

On July 3, 2024, I’ll be embarking on the Bark Europa from the port of Papeete, Tahiti (French Polynesia) for a 35-day journey to the Fiji Islands, by way of Tonga and whatever other islands the wind leads us to. Our precise route will be determined by the Captain, the weather, and the permits of the local authorities.

3. How am I getting there?

What exactly is this Bark Europa of which I speak? Well, she’s a square-rigged, steel-hulled barque that sails under the flag of the Netherlands and is owned and operated by a Dutch company.

Sailing a variety of routes, the Europa often spends her summers in the Antarctic and the Southern Ocean. (As I write this, she just left Pitcairn Island, home to the HMS Bounty mutineers c. 1780s, and South Georgia Island, where Ernest Shackleton landed in 1916 after an 800-mile journey from Elephant Island to arrange the rescue of his crew. Yeah, I might be a little obsessed with the Southern Ocean . . .)

This past fall, the opportunity arose for me to sign on as voyage crew on the Bark Europa on this Tahiti-Tonga-Fiji route. Deep into my obsession with Alfred Agate and the USXX, it seemed like a sign. And sometimes, you just have to say yes to the universe.

Now, for my sailing experts (and to avoid sounding like the neophyte I am regarding all things sail), here is some text lifted in its entirety from the Bark Europa website giving the nitty gritty details on the ship:

Rigged as a bark, the Europa carries twelve square sails in total: six on both the fore and the main mast. The mizzen mast carries the spanker and the gaff topsail. Moreover, she carries ten staysails, to be found between the masts and between the jibboom and the foremast. Sailing broad reach in seas with winds up to 5 Beaufort, Europa can carry six studding sails. In total, a huge area of canvas that has to be set and manned by a lot of hands.

When not under sail, Europa has two Caterpillar 380 HP diesels driving two propellers. For manoeuvring, the ship also has a DAF 180 HP engine that drives a bow thruster and the anchor winch. Both are used in shallow waters, when hoisting anchor and when finding a way through the ice. Bunker capacity for diesel fuel is limited and diesel is also needed to drive the generators for electricity.

This, my friends, is not a Carnival Cruise with unlimited umbrella drinks, a Guy Fieri 24-hour burger buffet and luxury Platinum cabins:

No, as a member of the voyage crew, I’ll be standing watch, acting as helmsman/lookout, climbing the rigging, and practicing all those knots I learned when the boys were in Scouts. (I’ll also learn what the spanker and jibboom are!)

It’s also going to be an experience of slow travel and a return to the pre-internet, pre-smartphone world. There’s satellite communication onboard, but that’s it, and I’m told one pays about $1 per KB for email messages, so don’t expect any Instagram or blog posts from me for the duration (unless we should happen upon an internet café!)

Finally, there will be about 65 people aboard, consisting of crew and passengers.

Feel free to leave a comment if there’s something else you want to know!

For my next post I’ll be giving a little history of the US Exploring Expedition and after that, stories and images of Tahiti, Alfred Agate-style.

If you haven’t already subscribed and are interested in following this journey, you can do so here:

You can also follow the route of the Bark Europa here updated in real time.

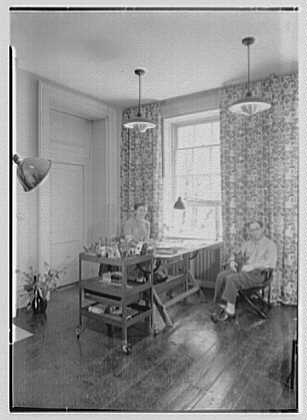

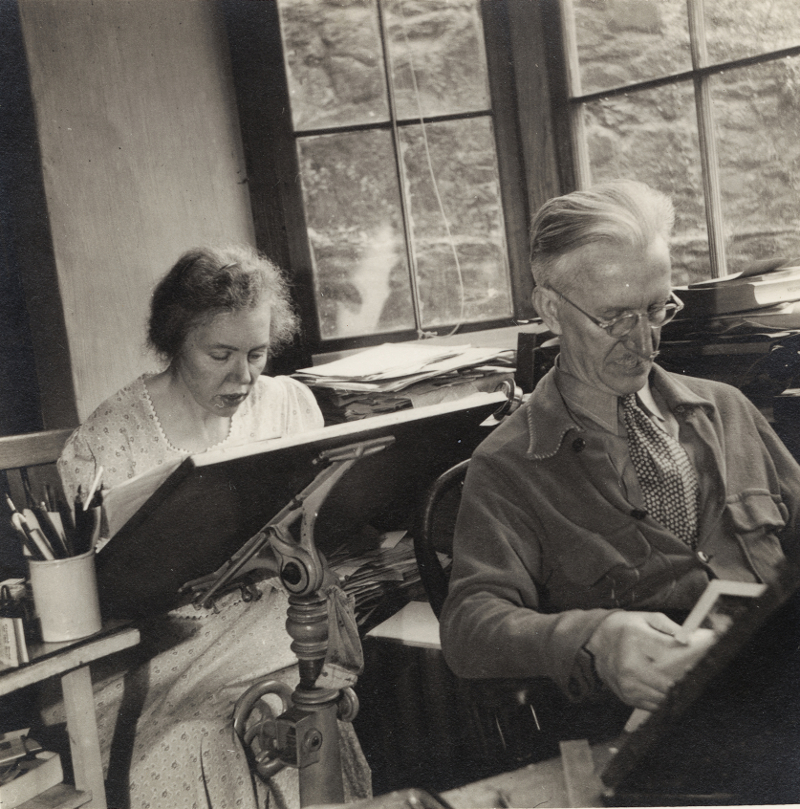

Berta and Elmer Hader in their studio in Nyack, NY (Courtesy of Concordia University)

Berta and Elmer Hader in their studio in Nyack, NY (Courtesy of Concordia University)