Today’s post will detail the very important cultural ritual of the Polynesian feast, something I was privileged to experience while in Tonga.

First, some context and history . . .

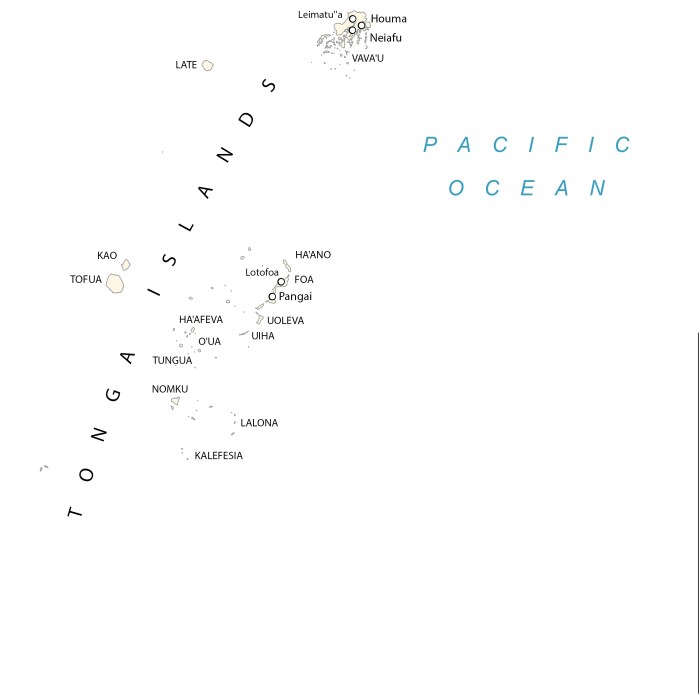

From July 24 – 27, 2024, I was on Vava’u, an island in the Kingdom of Tonga. Tonga is an archipelago that consists of 169 (or so) islands, of which 36 are inhabited. Vava’u is, unsurprisingly, one of the largest islands in the northern Vava’u group.

Courtesy of GISgeography.com

Interestingly, Tonga is the only Polynesian country that has never been officially colonized. In 1900, it became a British protective state but did not relinquish its power or independence.

Tonga and neighboring Samoa are considered the western gateway to what we call the Polynesian Triangle (which consists of Hawaii to the north, Easter Island to the east and New Zealand to the west.) According to Christina Thompson’s excellent book Sea People, Tonga is where the “oldest languages, longest settlement histories and deepest Polynesian roots” can be found.

It’s believed that Tonga and Samoa have been inhabited for about 2,500 years. Traditional Tongan and Samoan histories tell of an empire that was ruled by Tui Manu’a – both a man and a god. In about 950AD, the first Tu’i Tonga, Aho’eitu (considered the son of god Tangaloa) began expanding his reach, turning Tonga into a superpower that controlled much of what is today’s central Polynesia. Tongan hegemony would hold through the 13th century when civil wars in Tonga and Samoa weakened the empire.

As far as the European presence goes in Tonga, the Dutch first put these islands on maps. First, Schouten and Le Maire stopped here in 1616 (the year William Shakespeare died, just for a bit of context) learning some of the local language while trading for yams, pigs, bananas and fish. In 1642, Dutch explorer Abel Tasman limped through here after his disastrous encounter with the Maori of Aotearoa (New Zealand) and was relieved to note that the islanders in Tonga seemed friendly and eager to trade.

Captain Cook of Great Britain passed through here in 1773 and dubbed them the “Friendly Islands” due to the royal reception he received from the locals. And we can’t forget that the infamous mutiny of the Bounty happened about 30 miles east of the Tongan island of Tofua. Captain Bligh and his 18 loyalists would land their open launch and briefly take shelter in a cave on the northwest coast of Tofua Island. Bligh would write up his report of the mutiny here, as well as a letter to his wife as he directed his men to assess their supplies.

And in April 1840, our US Exploring Expedition briefly stopped at Tongatapu (today considered the main island of Tonga) for about a week. Expedition leader Lt. Charles Wilkes primarily planned to use it as a rendezvous point for his four remaining ships, as some had gone south to explore Antarctica, and some had been in Sydney for repairs.

Unfortunately for us, Wilkes had little interest in the islands, as he was much more concerned with getting to Fiji and securing advantageous treaties for the US regarding the lucrative whaling and bêche de mer industries.

However, while in Nukualofa on Tongatapu, Wilkes inserted himself as a negotiator into a local war between two native groups – the Christians, led by King Josiah (or Tubou) and the (so-called) “Devils,” those who did not follow the Christian teachings of the London Missionary Society. I am hard-pressed to understand Wilkes’ part in a peaceful end to this feud, as his writing on this is as impenetrable as it is condescending. Suffice to say, the disagreement seems to have resolved itself in spite of Wilkes’ meddling. And today Tonga considers itself a Christian nation, with 99% of the population identifying as Christian.

Here’s an illustration by Alfred Agate of the residence of King Josiah (Tubou) on Nukualofa:

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Now, onto feasts!

One of the things that Lt. Charles Wilkes constantly writes about in his Narrative are the feasts and rituals he attended. These could take hours or even days and were essential to attend to meet and connect with the various chiefs and leaders.

And while Wilkes was the big chief of the USXX, other officers were also tapped to attend these feasts in his stead at times. I know that Alfred Agate attended many of these himself, though perhaps not one in Tonga.

While in Vava’u, I was privileged to be invited to an umu, a traditional Tongan feast, hosted by Europa crew member Vi Latu and her extended family. As Vi explained to us, this was her family’s way of welcoming us to Tonga.

As we arrived on Ano Beach, the palm trees were gently blowing and the sun was setting. The entire area was taken up with an underground oven, an enormous tent and long table, an area for musicians and dancing, and local artists displaying their crafts.

What’s remarkable, is that many of the traditions on display in 2024 are quite similar to those described by Wilkes in his Narrative. So please indulge me as I’ll describe the traditional feast I attended using lightly edited excerpts from the Narrative of the US South Seas Exploring Expedition (published in 1845), and illustrated with photos from 2024.

Note that what follows is a compilation of observations Wilkes made throughout the South Pacific (primarily Tahiti, Tonga, Samoa, Fiji and Hawaii.) Taken together like this, we get a sense of the deep cultural connection between these Polynesian nations, as well as seeing how the ancient traditions are still intact and observed today.

Wilkes’ observations are italicized below. Mine are not.

The feast takes many hours to prepare and is generally directed by the women, with the men performing the labor. First, the cooking-place is excavated, a foot deep and about eight feet square:

The meat is placed upon hot stones after which taro, yams and coconuts are placed. Finally, it is all covered with banana leaves and earth. After many hours, the oven is unpacked of all its good things . . .

There is an abundance of fish. They likewise have fine crabs, and they are also generous with fowls and pigs.

Their feasts are attended with much ceremony and form . . .

Our feast began with Vi explaining all the delicious foods that were being served to us and how best to eat them.

Photo courtesy Andrew Willshire

Then we were asked to take our seats at the long table, and the most senior man of Vi’s clan blessed the meal. (I did not feel comfortable taking a photo of this.)

Then, we were encouraged to dig in, using our hands (although forks were provided.)

The first course consists of fish, some steamed in banana leaf, and some served in banana trunks. The second course is taro, yams & kumara, with fruit and bananas offered as well. The third and principal course consists of meat – whole piglets are served and then disjointed.

The piglet was sliced at the table with a machete. We were encouraged to tear off chunks and enjoy.

After the third course, dancing, music, stories, and kava-drinking succeed . . .

What is remarkable to me is how little the traditions have changed. One of the only differences I noted between Wilkes' descriptions and what I experienced was that the feast I attended only took four hours.

Also, I think it’s edifying to note that kava, which is a soporific that makes one a bit loopy and anesthetizes the mouth, is no longer prepared in the way Wilkes observed in his Narrative:

The younger women prepare the kava and are required to have clean and undecayed teeth. They are not allowed to swallow any of the juice, on pain of punishment. As soon as the kava-root is chewed, it is spit into the kava-bowl, where water is poured on it with great formality. The king's herald, with a peculiar drawling whine, then cries "Sevu-rui-a-na," (‘make the offering.’) After this, a considerable time is spent in straining the kava through cocoa-nut husks. Kava is made from the Piper mythisticum, and it is the only intoxicating drink they have.

Wilkes in fact refused to drink the kava thus prepared and his hosts, on at least one occasion, gave him coconut water instead. (I feel the need to note that Captain Cook often drank the kava.) After speaking to Vi, her family and others throughout Polynesia, it’s been reinforced what an important part of the culture kava drinking still is. Back in the 1840s, refusing to participate fully in a kava ceremony would, I think, have been curious at best and a terrific insult at worst.

Fun fact: Later on, I visited the village of Naseva, on the island of Beqa in Fiji and took part in a traditional kava ceremony where I got to see how the kava is made:

Today, dried kava root is ground into a powder then rehydrated and strained through a cloth when needed. Chants are still sung as this takes place.

Wilkes’ description of a kava ceremony in Fiji is completely recognizable to me, as it is quite similar to what I experienced:

The kava-bowl was three feet in diameter. In drinking the kava, the first cup was handed to [the chief], and as there was more in it than he chose to drink, the remainder was poured back into the bowl. The ceremony of clapping of hands was then performed.

We were instructed to clap once before we received the bowl (made of half a coconut shell), then drink the whole thing down, and clap three times after we handed the empty bowl back. (And yeah, if someone didn't finish their bowl, it was poured back into the big kava bowl. And then served back out.)

And what is kava like? I cannot tell a lie, I did not enjoy it much – it tastes like it looks, like gritty, muddy water. And your mouth feels like you’ve just had the rinse the dentist gives you before a root canal. Other than that, I don’t think I drank enough to feel the full effects . . . However, I greatly appreciated the ritual and attention to welcoming visitors. We could all stand to take the time to greet people expansively and properly.

Still more to come . . .

Sign up here if you’re interested in following this 2024 voyage to the South Pacific:

Thrilling! Tonga has been in my memory ever since Queen Salote walked barefoot in Queen Elizabeth’s coronation parade.Barbara W

LikeLiked by 1 person